|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

YELLOW-BELLIED SAP-LAPPER

Each winter for at least the past 25 years a gnarly old Pecan in the front yard at Hilton Pond Center has been unsuspecting host to a couple or three smallish birds that may not be doing the tree a favor. The birds arrive in fall from points unknown--perhaps as far north as boreal Canada or as near as the Southern Appalachians--and set up shop on the Pecan's trunk and main limbs. We usually know they've arrived when we hear them communicating with a soft, almost cat-like mewing, but sometimes we're alerted by their rhythmic tapping on the tree--something that sounds like the work of a woodpecker. Indeed, the tapping IS from a woodpecker, but a very different one whose recognized name--Yellow-bellied Sapsucker--is misleading. In our judgment, "Yellow-bellied Sap-Lapper" would be more accurate and appropriate, for reasons outlined below.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center During winter days here at Hilton Pond Center, the rat-a-tat-tat of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Sphyrapicus varius, is different from that of most woodpeckers, softer and not as long as, for example, that of an industrious Red-bellied or Downy. Despite their name, sapsuckers don't really suck sap as it oozes from the tree. Very few birds are capable of sucking up liquids, some notable exceptions being members of the pigeon and parrot families. Most birds merely dip their bills into standing water, scoop the liquid with their lower mandibles, and tilt back their heads as water runs down their gullets. A few of the non-suckers, including sapsuckers and hummingbirds, have modified tongues that allow them to drink sap or nectar by lapping it. (NOTE: It's a common misconception that hummingbirds--and even woodpeckers--use their long bills like straws to suck up fluids. In reality, a hummer can stick its tongue out as much as the length of its bill when lapping up nectar.)

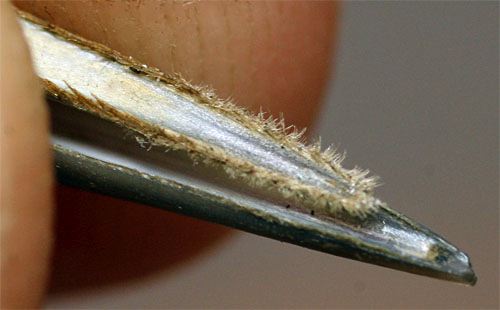

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Typical woodpecker tongue tips are spear-shaped and with tiny rear-pointing barbs along the edges; when the woodpecker skewers a fat beetle larva, the barbs grab fast inside the grub and allow the woodpecker to extract its succulent prey from its hiding place within the tree. In contrast, the sapsucker's tongue is more flexible and has a feathery edge (above); its tiny hair-like projections make use of capillary action and efficiently draw liquids into the sapsucker's mouth as it flicks its tongue in and out of the nearest sapsucker well. It is for this reason we contend the bird in question should be called a Yellow-bellied "Sap-Lapper" rather than "Sapsucker."

The Western U.S. is home to two additional sapsuckers--Red-breasted and Williamson's; for us, the most prominent plumage characteristic of the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker and its relatives is a distinctive white shoulder patch formed by several greater and lesser secondary covert feathers (below). The Yellow-bellied Sapsucker also has white spots on its primary and secondary wing feathers, and the back is spotted black and white; in adults, both sexes have a small crest and forehead that are red, and the male (below) has a red throat. Recently fledged yellow-bellieds look nothing like the adults, being mostly brown and lacking any red color, although juveniles do have the prominent white wing bar. By late February, last year's young have acquired most of their adult plumage; the forehead of some--as below--may still show a few brown feathers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the hand, Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers reveal all sorts of interesting anatomical characteristics. A close-up of the bill, for example, shows it is not conical and sharply pointed. In lateral view (below left), we see the upper mandible is actually squared off at the tip, and from the front (below right) it is beveled side to side. This shape indicates the woodpecker uses its bill less like an ice pick and more like a chisel or wedge that pries small chips of wood from a tree. (We also noticed in side view a groove leading from the edge of the sapsucker's upper bill to the nostril. We're not sure what the function of this structure might be, but it's also found in Downy Woodpeckers and not in species such as Red-bellied Woodpecker or Common Flicker.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center A photo from beneath shows the sapsucker's tail (below)--like that of most woodpeckers--has specialized feathers with a shape unlike that of other birds. Each rectrix (tail feather) is tapered at the tip, and the central shaft is thick and very stiff. This allows the sapsucker to use its tail as the third segment of a tripod, with the other segments being its right and left legs. As anticipated, the tripod provides stability while the woodpecker hammers a tree with its bill. It's worth noting that woodpeckers typically move UP a tree, which allows the tail feathers to slide unimpeded along the trunk; if a woodpecker regularly moved DOWN a tree, sharp ends of rectrices sooner or later would get caught in tree bark and break off. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of the sapsucker's climbing appendages, a close-up photo of its foot (below right) shows another attribute of the Picidae (Woodpecker Family). Most birds--including all our familiar songbirds (warblers, robins, finches, etc.)--have three toes in front and one (the hallux) to the rear, an adaptation for perching. Feet with permanent 2 x 2 alignment like a woodpecker's are said to be "zygodactyl," while 3 x 1 is "anisodactyl." (Owls and a few other birds can swivel the outside toe from front to back, hence the term "semi-zygodactyl.") The photo above right also shows the sapsucker has very stout talons that rival those of a hawk--the better to hold fast to irregular nooks and crannies of tree bark. (By comparison, nuthatches--which are also bark clingers--are anisodactyl but with a very long hind toe and claw; this allows them to work the tree head-down rather than head-up like the sapsucker.) We should point out that even though sapsuckers are adapted to sap-lapping, they also take other foods--including insects such as ants, bees, and caterpillars attracted to sap flowing at the sapsucker's well. Such insects are very important in a sapsucker's diet as sources of fats and proteins. Patient homeowners have been able to attract sapsuckers to backyard feeding areas with suet, grape jelly, and even stale doughnuts. These birds also eat wild fruits and have been observed feeding on holly berries alongside flocks of Cedar Waxwings and American Robins. We were delighted last spring and summer to observe an active sapsucker well on an ornamental Paper Birch at Mountain Lake Hotel in Virginia. Folks sometimes ask if Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers that make their feeding holes in live vegetation can actually damage a tree. In some cases--as in a three-inch-diameter Flowering Dogwood that once grew at Hilton Pond Center--a busy sapsucker worked so hard at excavating it removed all bark in a five-inch-wide band and girdled the tree, causing its demise.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT #1: During our 2006 Operation RubyThroat hummingbird banding expedition to Guancaste Province, Costa Rica, we took the group on our traditional day trip to Santa Rosa National Park. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT #2: Jeff Wells, senior scientist with the Boreal Songbird Initiative, tells us more than 50% of the total populaton of Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers breeds in the Boreal Ecoregion of Canada and Alaska--an area that "contains some of the world 's most intact forests and wetlands" and much of which is threatened because it "has been allocated for resource development." All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Comments or questions about this week's installment?

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond."

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written & photographed You may wish to consult our Index of all nature topics covered since February 2000. You can also use our on-line Hilton Pond Search Engine at the bottom of this page. For a free, non-fattening, on-line subscription to |

We imagine the sapsucker is a much louder 'pecker up north when excavating a nest hole or drumming out his territorial signal to rival males or prospective mates, but here in the Carolinas we've not observed the kind of incessant tapping we hear from other woodpeckers when they're after beetle grubs hiding in dead snags. The difference in drumming intensity no doubt is due to the sapsucker's highly specialized feeding behavior, which involves making horizontal rows of quarter-inch round holes in living trees, shrubs, and vines. These tell-tale holes (old ones in the gnarly Pecan, above right) are referred to as "sapsucker wells"--founts through which sap flows forth, providing a tasty, carbohydrate-rich treat for the sapsucker. It shouldn't be a surprise that another tree species frequented by sapsuckers is the Sugar Maple (below left);

We imagine the sapsucker is a much louder 'pecker up north when excavating a nest hole or drumming out his territorial signal to rival males or prospective mates, but here in the Carolinas we've not observed the kind of incessant tapping we hear from other woodpeckers when they're after beetle grubs hiding in dead snags. The difference in drumming intensity no doubt is due to the sapsucker's highly specialized feeding behavior, which involves making horizontal rows of quarter-inch round holes in living trees, shrubs, and vines. These tell-tale holes (old ones in the gnarly Pecan, above right) are referred to as "sapsucker wells"--founts through which sap flows forth, providing a tasty, carbohydrate-rich treat for the sapsucker. It shouldn't be a surprise that another tree species frequented by sapsuckers is the Sugar Maple (below left);  after all, when we humans tap a maple for its sweet sap we're merely imitating what sapsucker clans have been doing for hundreds of thousands of years.

after all, when we humans tap a maple for its sweet sap we're merely imitating what sapsucker clans have been doing for hundreds of thousands of years.

Some observers might even question whether this bird should be called "Yellow-bellied" at all, since it's not often one gets a good view of the tree-hugging woodpecker's ventral plumage. Indeed, the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (right) AND Red-bellied Woodpecker likely were named by collectors or curators who first saw these birds on their backs as museum specimens and noticed the otherwise seldom-seen color of the belly feathers.

Some observers might even question whether this bird should be called "Yellow-bellied" at all, since it's not often one gets a good view of the tree-hugging woodpecker's ventral plumage. Indeed, the Yellow-bellied Sapsucker (right) AND Red-bellied Woodpecker likely were named by collectors or curators who first saw these birds on their backs as museum specimens and noticed the otherwise seldom-seen color of the belly feathers.

.

.

Woodpeckers instead have two toes in front and two in back, with the outside front toe elongated and rotated to the rear. This configuration isn't as well-suited to horizontal perching but improves stability in a bird that spends its life clinging to vertical surfaces such as tree trunks.

Woodpeckers instead have two toes in front and two in back, with the outside front toe elongated and rotated to the rear. This configuration isn't as well-suited to horizontal perching but improves stability in a bird that spends its life clinging to vertical surfaces such as tree trunks.  The tree had dozens of holes in it, most of which were oozing small amounts of sap. The resident sapsuckers (adult male, below left) made frequent visits to lap and tap, keeping their many holes open and flowing so they could drink at the well. Occasionally, a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird would zip to the well (below right), stealing a little sweet juice. In northern latitudes, such interaction between sapsuckers, sapsucker wells, and hummingbirds may be vitally important, especially if the hummingbirds happen to arrive on their northerly breeding grounds just after a cold snap kills off early-blooming nectar plants. Without sapsucker wells, at least some earlybird hummers might perish for lack of carbohydrates.

The tree had dozens of holes in it, most of which were oozing small amounts of sap. The resident sapsuckers (adult male, below left) made frequent visits to lap and tap, keeping their many holes open and flowing so they could drink at the well. Occasionally, a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird would zip to the well (below right), stealing a little sweet juice. In northern latitudes, such interaction between sapsuckers, sapsucker wells, and hummingbirds may be vitally important, especially if the hummingbirds happen to arrive on their northerly breeding grounds just after a cold snap kills off early-blooming nectar plants. Without sapsucker wells, at least some earlybird hummers might perish for lack of carbohydrates. (As a precaution, we wrapped wire mesh around a couple of other sapling dogwoods until the sapsucker created wells on older, more established trees.) With regard to the gnarly old Pecan in front of the Center's farmhouse, we suspect generations of sapsuckers that made holes numbering tens of thousands HAVE had an impact because that particular Pecan is growing much more slowly than its peers on the property. For the most part, however, Yellow-bellied Sap-lappers (immature male below) probably have minimal impact on most trees that share their sugar-laden fluids via sapsucker wells, so we're always glad to see and hear these woodpeckers each fall as they fly in from faraway points.

(As a precaution, we wrapped wire mesh around a couple of other sapling dogwoods until the sapsucker created wells on older, more established trees.) With regard to the gnarly old Pecan in front of the Center's farmhouse, we suspect generations of sapsuckers that made holes numbering tens of thousands HAVE had an impact because that particular Pecan is growing much more slowly than its peers on the property. For the most part, however, Yellow-bellied Sap-lappers (immature male below) probably have minimal impact on most trees that share their sugar-laden fluids via sapsucker wells, so we're always glad to see and hear these woodpeckers each fall as they fly in from faraway points.

There we examined the flora of a tropical dry forest and were startled to see the trunk of a Cecropia tree (right) bearing horizontal rows of quarter-inch holes--sure sign of a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker. Some sapsuckers--which breed as far north as boreal Canada--do indeed fly as far south as Costa Rica (and even to Panama), where they're called Carpintero Bebedor--translated literally as "hard-drinking carpenter." This all leads us to wonder if any of our Ruby-throated Hummingbirds from North America ever partake of sweet juice from sapsucker wells on hot "winter" days in the Neotropics.

There we examined the flora of a tropical dry forest and were startled to see the trunk of a Cecropia tree (right) bearing horizontal rows of quarter-inch holes--sure sign of a Yellow-bellied Sapsucker. Some sapsuckers--which breed as far north as boreal Canada--do indeed fly as far south as Costa Rica (and even to Panama), where they're called Carpintero Bebedor--translated literally as "hard-drinking carpenter." This all leads us to wonder if any of our Ruby-throated Hummingbirds from North America ever partake of sweet juice from sapsucker wells on hot "winter" days in the Neotropics.

Oct 15 to Mar 15

Oct 15 to Mar 15