|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

NOTE 1: We spent more than four weeks banding hummingbirds in Costa Rica in early 2009. The following account is for Week Four, a wrap-up week. Accounts are now posted for Week One, Week Two and Week Three; we recommend you read the accounts in chronological order to better understand the whole sequence of events. Every week was different, so we hope you enjoy all the summaries. NOTE 2: A least four more nine-day Operation RubyThroat tropical hummingbird expeditions are scheduled for January-March 2010 to Central America (Costa Rica and--for the first time--Guatemala and Belize). For more information see 2010 Tropical Hummingbird Banding Expeditions and contact EDUCATION.)

HUMMINGBIRDS IN COSTA RICA: Late on the morning of 21 February 2009--as Week Three came to a close for our 2009 Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Costa Rica-- 21 FEBRUARY (OMEGA NINERS) Earlier on 21 February we (the Omega Niners) had transferred net poles, mist nets, and banding gear from the bus into Ernesto's car so everything would be available for field use. As soon as the last outbound group member disappeared into Liberia's airport we went for a late lunch and then made our way back to the Aloe Vera plantation at Cañas Dulces. We navigated bumpy roads and streams past AV3 and AV5, the two sites where the Alpha Niners and Gamma Niners had captured 104 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds during 12 field days in 2009. Our destination, however, was AV7--the seventh plot in a string of nine (see aerial photos in Part 1 of the Summary Section, below). Although this locale had been quite productive for us in 2008 during two days of end-of-expedition banding (10-11 February), it was accessible only by Ernesto's four-wheel drive vehicle. Because of a deep stream our larger groups couldn't get to AV7 on foot or by bus, so we were eager to see if this remote site would yield more hummers in 2009.

We arrived at AV7 at about 3:50 p.m. on 21 February, found an acceptable but not overwhelming number of plants in bloom, and went to work setting up mist nets in edge-hugging lanes we used successfully last year. (The photo above was made in 2008 when there were many more aloe blooms than this year.) At 4 p.m. we captured our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird and netted six more by 5:10 p.m. In all that afternoon we banded seven RTHU: four fully gorgeted adult males, a second-year (juvenile) male, and two females--not bad for 80 minutes of net time. It was good to know there were quite a few hummers in AV7. After shut-down at dusk we rode back up to Buena Vista Lodge for the night. 22 FEBRUARY (OMEGA NINERS) Next morning--22 February--we Omega Niners arose with a great sense of anticipation, mostly because we thought we'd get an earlier start in AV7 and capture lots of birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Arriving at AV7 at about 6:50 a.m., the Omega Group quickly had several nets in place and began clearing two other net lanes in a spot where we'd seen several hummingbirds the previous day. With little shade available, we used Ernesto's car as a sunblock (above) and set up the banding table beneath the open tailgate. Our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird was snared at 7:10 a.m. and the hummers came regularly thereafter--so frequently Ernesto had no time to prepare a delicious and filling hot breakfast of oatmeal with brown sugar until well after 10:30 a.m. (Lunch was also delayed, with Chef Ernesto's amazingly tasty whole wheat crackers spread with refried beans in Lizaro's "lizard sauce" not served until mid-afternoon.) To shorten considerably the all-day 22 February account, by the time we shut our nets at 5 p.m. the Omega Group had banded an incredible 29 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--a new one-day record for us in Costa Rica. (Crazy '08s Omega held the old record with 25 RTHU banded in AV4 during just a three-hour span on 7 February last year. Now THAT was an exhausting morning!) This phenomenal 2009 tally included two partially gorgeted second-year males, nine red-throated adult males, and 18 adult females.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Did we mention that in addition to our 29 ruby-throats on 22 February this year we also caught and banded a Painted Bunting, a Tennessee Warbler, a Yellow Warbler, and three Orchard Orioles? But even that wasn't as important an accomplishment as when we captured a female Orchard Oriole that--as Ernesto took her from the net--revealed she was already tagged with an aluminum band (above) that was NOT bright and shiny like those we had just applied to the other orioles. ANYtime a bander catches a bird with an old band it is cause for anticipation and excitement, so we carefully read and wrote down the number on this bird's leg: 2281-11807. Having just banded three other Orchard Orioles in AV7, we instantly recognized the four-digit prefix as one we had been using in Costa Rica; a further check of our records indicated we banded this particular Orchard Oriole in AV3 with Crazy '08s Alpha on 28 January LAST YEAR! At that time we classified her as an adult female that must have hatched at least in 2007, so at time of recapture this year she was at least an "after-second-year" bird. This returning Orchard Oriole, Icterus spurius, was cause for jubilation, for it was the first time we had ever re-encountered a non-hummingbird in the tropics at essentially the same location where we banded it. (The straight-line distance between AV3 and AV7 is less than a half-mile.) A return like this is quite important because it shows conclusively that Neotropical migrant Orchard Orioles--which breed across the eastern half of the U.S. and into the Central Highlands of Mexico--can show site fidelity on their wintering grounds. We were already first to demonstrate this phenomenon for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--three of which we recaptured in Cañas Dulces a year after banding them among the aloe--so with hummers AND orioles we now have evidence aloe plantations in the Neotropics may be more important to wintering migrants than anyone knew. (More about this concept below.) With 29 ruby-throats banded and a returning Orchard Oriole to boot we Omega Niners were riding pretty high by the end of the afternoon, but we still had two more things to accomplish by day's end: 23 FEBRUARY (OMEGA NINERS)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After dreaming all night about the Steelers' victory--and, of course, about hummingbirds--we leapt from bed on 23 February, eager to go back to see what we might accomplish in AV7. Our breakfast was later than "normal" because the Lodge's kitchen staff understandably didn't get up early for two-person groups like us Omega Niners. Nonetheless, we were able to get to the study site and have nets open in time to catch our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird by 8:30 a.m. Things started well but slowed considerably as the morning progressed, so we decided to shut down at noon after banding 14 ruby-throats. Along the way we banded 14 non-hummingbirds, too--including NINE Orchard Orioles caught at 9:05 a.m., all in the same net! That morning the banding table also hosted two Yellow Warblers, a Tennessee Warbler, and two Blue Grosbeaks (male, above, and female). We measured and banded all of them, although it's possible the grosbeaks weren't actually Neotropical migrants but part of a resident population breeding in northwestern Guanacaste. That afternoon we explored the area and devoted a few hours to scouting for hummers and taking photos of several new flower species upon which we had observed ruby-throats feeding. The evening was devoted to packing up things at Buena Vista Lodge in anticipation of driving to San Jose the next day for a flight home to the Carolinas the day after that. 24 FEBRUARY (OMEGA NINERS) Following breakfast on 24 February we loaded luggage and banding gear into Ernesto's car and made one last drive down the mountain toward the Aloe Vera fields at Cañas Dulces. Because of the afternoon slow-down the day before at AV7 we elected to go back to AV5(South) where the Gamma Niners had been successful toward the end of their nine days in Costa Rica. This relocation wasn't nearly as productive as we had hoped; between 8 a.m. and noon we netted only three Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--one of our slowest days ever. We also caught one Yellow Warbler but the bird of the day in AV5 was ANOTHER female Orchard Oriole with an old band on its leg. This individual was 2281-11813, which our records showed we captured as a second-year bird in AV3 on 28 January 2008. This was the SAME DAY we banded 2281-11807--the female Orchard Oriole we recaptured on 23 February this year in AV7. So now we had further evidence Orchard Orioles that migrate away from the tropics to breed in North America show strong site fidelity upon returning to their wintering grounds in Costa Rica. How amazing it is that two birds we banded in AV3 on the same day in 2008 showed up one day apart the following year--and both in AV7!

With this final success for 2009 duly recorded, the Omega Group wondered whether the Laughing Falcon (above) perched overhead was laughing at us as we pulled all the nets, poles, and rebars, packed up the banding table and tools, loaded the car, and drove southeast on the Pan-American Highway. We lingered in Liberia for a final lunch at the Chinese restaurant, stopped for a last look at the past-its-prime-flowering condition of the aloe plantation at the Carrington facility, and headed out in the direction of San Jose. Almost five hours later we arrived at Finca Cristina--the Carman family's shade-grown fully organic coffee farm at Paraiso, where Ernesto met up with fiancee Ela and everyone got reacquainted with Ernie and Linda Carman, Ernesto's parents. 25 FEBRUARY (OMEGA NINERS) Next day (25 February) Ernesto and Ela gave us a tour of their new residence on the edge of Finca Cristina and were kind enough to make the shuttle run back across San Jose to the international airport. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 1)

Aerial photo (above) of Carrington Industries' Finca Sabila, two miles south of Liberia. Nets were deployed just outside the Carrington property underneath the tree line to either side of the blue dot. Following the departure of our three groups of citizen scientists, the Omega Group (Hilton & Carman) stayed on a few days to do some exploration and follow-up banding at the aloe fields near Cañas Dulces. We had already spent one additional day earlier in February banding around the northwestern perimeter of the Carrington Laboratories plantation (above).

Results of the Omega Niners' five days in the field are summarized on Table 1 (above). The 29 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds banded on 22 February was a record-high for one day in the field in Costa Rica.

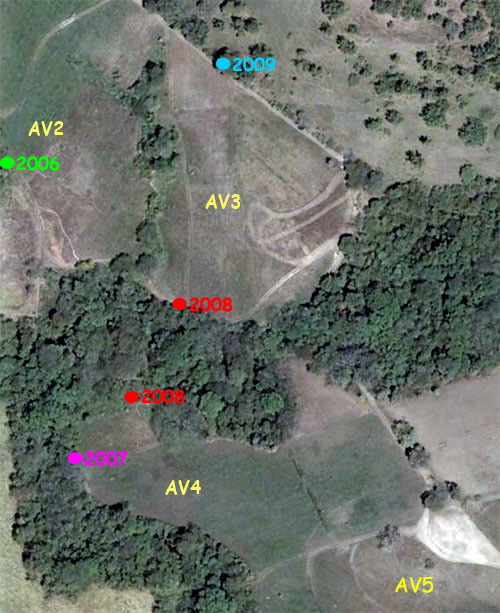

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Aerial photo (above) of Cañas Dulces Aloe Vera fields AV2, AV3, AV4, and AV5 (in part). Dots with dates are locations where the banding table was situated during given years.

Together, the Alpha Niners, Beta Niners, Gamma Niners, and Omega Niners spent 22 days in the field in 2009 and captured an astonishing 243 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (see Table 2 above). Among these was a great preponderance of females--almost 70%. Such apparent imbalance may have occurred because male RTHU are the first ton arrive on North American breeding grounds and, as a result, would be most likely to leave earlier from the Neotropics.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Aerial photo (above) of Cañas Dulces aloe fields AV4 and AV5. When nets were deployed in the northern section of AV5, we re-designated the two fields as AV5N and AV5S. The banding table location for both these is indicated by the blue dot.

The 243 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds banded in 2009 was a significant increase over our previous best--last year when we caught 170. The higher number was due in part to spending more days in the field--22 in 2009--but in general the groups simply did a better job catching hummers. Part of our success came when group members made pertinent observations about where ruby-throats were active and we subsequently added or shifted a few mist net positions. During the five-year project we have been in the field on 52 days--most being four-hour stints in the Aloe Vera plantations at Cañas Dulces or, this year, Carrington. We've averaged about ten RTHU banded per day. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Comprehensive aerial view (above) of the five Cañas Dulces aloe fields used during Years Two through Five. Because it is accessible only by four-wheel drive vehicle, AV7 has not been used by group participants but was quite productive for trip leaders during 2008-09. Nets were run in AV7 only along the north perimeter east and west of the blue dot. Despite the heavy imbalance between male and female ruby-throats in 2009, the sex ratio over our first five years is more even. It is remarkably close to the 3:2 ratio of females to males seen during our 26 years of banding ruby-throats back north at Hilton Pond Center. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 2) TABLE 4: Neotropical Migrant Species (Non-Hummingbirds)

Our federal Bird Banding Laboratory master permit to work in Costa Rica authorizes us to place U.S. bands on any Neotropical migratory bird, but not on resident non-migrants. Although we banded no non-hummingbirds our first year in Guanacaste, we decided in 2006 that if we have these birds in-hand we might as well band them. One never knows when a bird banded on its wintering grounds may teach us something about the species if it is encountered back in North America. Tennessee Warblers and Orchard Orioles (see Table 4, above) are by far our most commonly captured non-hummingbirds in the aloe fields--not surprising because these two species take nectar from many flower sources.

Although no non-hummingbirds banded in Guanacaste--including several male Painted Buntings (above)--have been encountered on their breeding grounds in the U.S. or Canada, two female Orchard Orioles banded on the same day last year in AV3 were recaptured two days apart this year in AV7. Such encounters with returning birds provide valuable information about winter site fidelity for Neotropical migrants. (See details under our anecdotal entries above for 22 and 24 February 2009.) All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 3)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When an adult Ruby-throated Hummingbird leaves North America in autumn, its feathers are pretty worn; a migrating bird-of-the year has the fresh plumage it fledged with, but juvenile feathers are not as well-formed. In either case it's vital for both birds to get a whole new set of feathers before making the trip back north, and that's just what happens. Every ruby-throat replaces every one of its wing, tail, and body feathers on the winter grounds. That's how, for example, juvenile males that leave the U.S. or Canada with white throats come back north the following spring with the full red gorgets they need to impress females. (The young male in the photo above has just begun to acquire his gorget. His juvenile throat feathers, lightly streaked with brown, are being replaced by metallic red ones--some of which are "in quill.") These youngsters also replace their rounded, white-tipped outer tail feathers with a set that is pointed and with dark tips. In other words, upon returning to the breeding grounds, second year males no longer look like females.

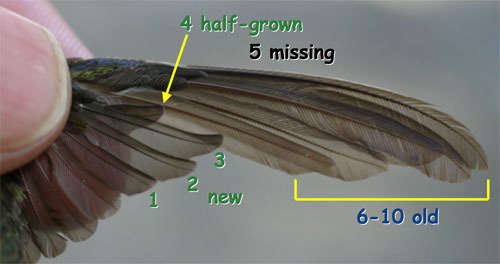

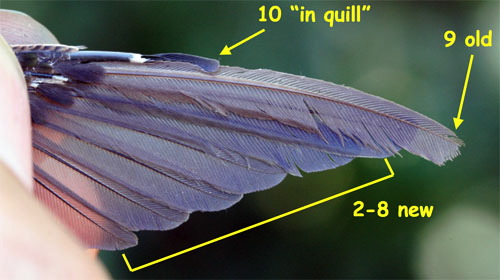

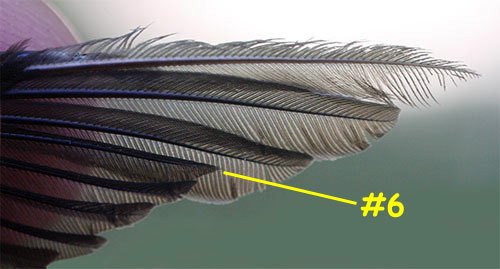

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By being in Costa Rica at various times during the past five winters, we've been able to make some interesting observations about molt timing & sequence among Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. For example, during our initial expeditions in late December 2004 and early January 2005, the Pioneers and Second Wave helped catch RTHU that were just beginning their wing molt--which begins with the inner #1 primary feather and moves outward until all ten primaries are replaced. In the photo above--taken in early January--the ruby-throat's wing has dark new primary feathers #1, #2, and #3; #4 has grown in part way; #5 is missing; and #6 through #10 are old, somewhat faded, and relatively worn. Compare that photo with the one below, which shows a wing molt much further along.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although primary #1 isn't visible in this late February photo (above), it and #2 through #8 are all fresh and new, as is #10. It's curious that #9--which is quite faded and worn--is being replaced out of sequence; i.e., the hummer brings in #1 through #8 in numerical order, skips #9, replaces #10, and then comes back and brings in a new #9--the wing's biggest feather. We speculate that this big #9--perhaps the "most important" primary--is replaced last as an adaptation that allows it to be the freshest feather when the arduous migration back north is about to begin. (Such speculation may not be correct, however, when we consider at least two resident, non-migratory hummingbird species we've netted in the aloe fields also demonstrated this out-of-sequence wing molt.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The wing feather photo above, taken in late February 2009, shows visible primaries (#2-#8) all fresh and new. Primary #9 is extremely worn, while #10 is just beginning to come in behind its left base. The wing is from a young Ruby-throated Hummingbird male, as indicated by the tapered, pointed #6 primary--a feather that is less tapered and more rounded in females. (See previous two photos of female wing molt, above.) This #6 primary can be used to conclusively determine sex in a white-throated bird that might appear to be either female or a young male. Sexing Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is easy and 100%reliable, but ageing them precisely is another matter. Any ruby-throat we capture in January or February on our Costa Rica study site is by default an "after hatch year" bird; i.e., it MUST have hatched out on North American breeding grounds prior to the current year. (By convention, all birds are said to become a year older on 1 January.) We can be more specific in ageing some males because those with white throats or partially red gorgets are "second year" birds that absolutely hatched the preceding year. Males with full red throats are more confusing, for they could have hatched the preceding year or in any of several years before that, so we typically just call them "adult" or "after hatch year." Most confusing of all are females, whose throat or body feathers do not change as noticeably from juvenile to adult. Up until now, we have simply called all females "after hatch year," but in 2009 we may have found a way to be more precise. Typically, head and back plumage in adult male and female ruby-throats is deeper, darker green, while those same feathers in juveniles tend to be browner. We noticed this year that several second-year males undergoing gorget molt also had new crown feathers that were green, but they still bore brown forehead feathers (above). This contrast between green and brown head plumage was quite pronounced in SOME males whose gorgets revealed they HAD to be second-year birds. As we got later into February we saw this same contrast in some females we captured, so we now suspect these birds might also be classified correctly as "second year." We made extensive notes about brown forehead birds we banded; if we recapture some in future years and they have GREEN forehead feathers being replaced by green--rather than BROWN being replaced by green--we'll confirm that forehead molt can be used to age at least some female RTHU on the wintering grounds. 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 4) Something quite fortuitous happened on the morning of 23 February. While the Omega Group was running nets in AV7, we finally got to talk with the owner of the Cañas Dulces aloe fields in which we had been working for five years. Prior to this meeting our contacts had all been with Franklin, a local resident who managed the farm. Alfredo also told us he lamented financial problems that had affected Carrington Laboratories and caused the company's aloe processing facility at Liberia to close in January 2009. Without this plant he had nowhere in Guanacaste to sell his aloe leaves, so he was hopeful--and confident--a buyer for the Carrington site would emerge fairly soon. This would be equally good news for Operation RubyThroat, considering the Beta Niners and Omega Niners had caught 86 hummers around Carrington's Finca Sabila plantation in early February and that our plan was to return there for at least a few days of banding in 2010.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When Alfredo matter-of-factly mentioned he also owned an Aloe Vera plantation near Guastatoya (map, above) in his home country of Guatemala, the collective jaws of the Omega Group dropped and our minds immediately began to spin--especially when Alfredo assured us he had seen winter hummingbirds among his fields 500 miles to the north. We asked if next year we might bring an expedition to Guatemala to find out if those particular hummers were the ruby-throats we would anticipate. Alfredo responded very positively so we soon enlisted Debbie Sturdivant at Holbrook Travel to help organize our first-ever Neotropical hummingbird foray into to El Progreso Province, Guatemala. The trip is slated for 13-21 February 2010 and will follow our two tried-and-true trips to Costa Rica in late January and early February next year. (We're still ironing out details of the Guatemala trip and will post them to Tropical Hummingbird Expeditions as soon as possible. We anticipate the Guatemala trip--like those to Costa Rica--will fill rapidly.) 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 5) In 2006 the Oh-Sixers ran mist nets for three days in AV2, where we captured 51 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. In 2007 the Lucky Sevens were elated when they recaptured in AV3 a ruby-throat banded (C51517, at right) as a partially gorgeted second-year male the preceding year.

The two groups from 2008 banded an unprecedented 170 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, so we were surprised and disappointed when none of those birds--or any from 2004-2007--were recaptured this year. However, with another 243 RTHU banded by groups in 2009 the odds of one or more of our 510 banded birds returning in 2010 seem pretty good. Of course, the Holy Grail of Operation RubyThroat in the Neotropics will be when we recapture a Hilton Pond ruby-throat on of our Costa Rican study sites, or vice versa. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 6)

Interestingly, at either location we seldom recaptured a bird that was already color marked and banded, which may indicate that most ruby-throats learn to avoid the mist nets. However, we did frequently SEE color marked hummers feeding among the aloe at both Cañas Dulces and Carrington. In fact, one marked RTHU at the latter site was still present at least ten days after banding.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This year color marking helped us reconfirm something we had suspected in 2004-05 but finally documented back in 2007: At least some male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds demonstrate territoriality on the wintering grounds. Three years ago we observed a fully gorgeted male perching on a tall Aloe Vera flower stalk and chasing away other hummers that came near. This year we watched a color-marked adult male foraging in and defending a much larger area about 20 yards by 20 yards. This particular individual (above, note blue color mark and aluminum band on left leg) was identifiable by behavior and by appearance so we were able to follow him for several days as he visited the same aloe stalks and drove away other ruby-throats encroaching on his turf. To our knowledge, territorial defense by Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on the wintering grounds had not been described prior to our observations in Costa Rica--even though it is well-documented within the breeding range. (Almost anyone in eastern North America who hangs a sugar water feeder is familiar with aggressive territoriality among ruby-throats.) We do not yet know whether young males or females also defend winter territories in the Neotropics, which they often do within the breeding grounds. 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 7) Sometime during the early 2000s, Ernesto Carman Jr.--our in-country guide and co-investigator--was working near Liberia with a graduate student who had placed radio transmitters on Rufous-naped Wrens. As Ernesto followed these wrens around, he chanced upon an Aloe Vera plantation at Cañas Dulces in which he observed many Ruby-throated Hummingbirds nectaring. He made a mental note and communicated the info to a Costa Rican ornithologist who, in turn, In 2006 we scheduled our Costa Rica trip for mid-February--six weeks later than we went the preceding year--and, sure enough, the Aloe Vera was in full bloom (below left, with second year male). This year (2009) we wanted to mirror success from 2008, so we scheduled our expeditions to begin in late January--having learned from past experience that ruby-throats would be visiting aloe fields in full bloom during that time period. Boy, were we wrong! When the advance group (Omega Niners) got to Cañas Dulces on 24 January 2009 we were chagrined to find very few Aloe Vera blossoms in ANY of the fields we had worked so successfully in past years--including in 2008 when there were copious blooms at exactly the same time of year. We now conclude specific Aloe Vera bloom times aren't as calendar-dependent as one might think. Aloe, an African succulent, is adapted for mostly dry conditions punctuated by occasional--even rare--precipitation. During the bountiful rainy season Aloe Vera plants go about their business of making succulent new leaves that absorb all the water they can hold. As the dry season arrives, lack of moisture stresses the aloe and triggers a flowering mechanism. When the flower produces seeds, these tiny repositories of DNA provide the aloe's genes with a way to survive for another generation--even if the mother plant eventually dies due to extended drought. The bottom line is aloe makes blossoms only after it has NOT experienced rainfall for a certain length of time--a period we now suspect is about two months. It so happens Guanacaste's 2008 rainy season was much wetter and longer than normal, with extensive flooding in the province into November. Thus, the soil--and the aloe--did not begin to dry out until much later, meaning the plants were not stressed in time for them to be in full bloom by the time we arrived in late January 2009.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's interesting the Cañas Dulces finca has an irrigation system with which workers can spray water on the aloe fields (above). Doing so serves two functions: 1) It keeps the aloe from flowering and allows the plants to devote energy to growing additional harvestable leaves; and 2) It allows the succulentous leaves to "fatten up." Obviously, for an aloe farmer the optimal time to irrigate is before the aloe becomes stressed AND just prior to harvest when big, turgid leaves sold by weight would bring more revenue.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At the well-tended Carrington farm, Finca Sabila, we were surprised in early February this year to find a vast sea of yellow (above); ALL the Carrington aloe plants were blooming simultaneously--even though there were very few blooms in the more "natural" fields at Cañas Dulces just ten miles north. As far as we could tell, the big difference was that throughout Carrington's plantation the ground beneath aloe was covered completely with black polyethylene sheets. We suspect plastic was laid down primarily to eliminate weed growth among the aloe, but it also must have kept the soil at just the right dryness level to trigger blooming. Even though it looked like Carrington had an irrigation system in place, we speculate the company was saving money in not using it--perhaps in anticipation of the January 2009 plant closure. To summarize, following a particularly short rainy season we might expect aloe blooms much earlier in January, while a really wet and/or long one could extend bloom dates well into February--as happened in 2009. So, if we travel to Costa Rica too late in February we likely will have aloe flowers, the adult male ruby-throats may already be on their way north. If we go too early in January adult males should still be present, but a scarcity of blooming aloe makes it harder to capture hummers for banding. Unfortunately, we have to schedule our Operation RubyThroat expeditions a year in advance--long before we have any inkling of the length or intensity of the upcoming year's rainy season. Although when to go is always a gamble, if we hit it just right the pay-off is bound to be good. Such are the trials and tribulations of a field project in which we can't control natural variables. (NOTE: During our conversation with him, Alfredo Oliva Veliz--owner of the Cañas Dulces aloe farm--confirmed our suspicions about aloe flowering phenology. Alfredo told us in his experience aloe plants in Costa Rica and at his other farm in Guatemala do not usually bloom until about two months after the rainy season terminates.) 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 8) Aloe Vera, an African succulent, is not native to Costa Rica, but now that it is planted commercially in Guanacaste Province it may have taken on an important ecological role. Unquestionably, Aloe Vera is a very useful plant for wintering Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. That we have been able to capture more than 500 RTHU during the past five years at the Cañas Dulces and Carrington plantations is more than enough evidence this species is attracted by aloe nectar--and perhaps by tiny insects that also drink the juice. We suspect aloe fields in Guanacaste support the densest concentrations of wintering ruby-throats in Costa Rica; in fact, these plantations could have more RTHU per hectare for a longer winter period than any other site in Central America. (It's always amazing to us that after setting up mist nets in the aloe fields the great majority of what we catch are Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--the very target species we seek!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center There's no question RTHU have overwintered in Guanacaste in the distant past; they have been feeding on Costa Rican trees, shrubs, vines, and forbs for as long as human observers have kept ornithological records. These days when we travel away from the aloe fields around Liberia, we often see ruby-throats darting across the road or nectaring on a wide variety of native flora. Never, however, do we see the species in dense concentrations; they only occur as individuals or occasionally in small clusters of a half-dozen or so--feeding in a particularly healthy expanse of such plants as Blue Porterweed or Lantana, or in the topmost branches of flowering trees like the Inga (above) or Pochote.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A number of other Neotropical migrant birds also make direct use of the aloe fields in Guanacaste. We have observed several nectarivores--particularly Baltimore Orioles (adult male, above) Orchard Orioles, and Tennessee Warblers--that compete directly with Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, but other species capture insects and/or eat weed seeds within or above the aloe. These include at least the 12 non-hummingbird migrants we have banded (see Table 4 in "Summary Report: Part 2," above), particularly Barn Swallow, Painted and Indigo Buntings, Yellow Warbler, and Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Add to these numerous Costa Rican resident species we've observed and/or netted but did not band (White-collared and Variable Seedeaters, Stripe-headed Sparrow, Common Ground-Dove and Inca Dove--to say nothing of seven other species of hummingbirds) and the number of birds using aloe fields really starts to grow. There are also quite a few species that nest or feed in the edges surrounding aloe fields--we've caught everything from Long-tailed Manakins to Long-billed Gnatwrens to Great Kiskadees--and these, too, add to the list of birds that make direct or indirect use of aloe plantations.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center So what's our point? Obviously, plantings of non-native Aloe Vera are used by Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and other Neotropical migrant and resident birds in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica. However, these aloe fields are not natural--they're monoculture row-plantings of an import from Africa--but at least most of them are organic. (In fact, Carrington's fields are marked by large signs saying they are "organically certified.") That means aloe farmers are not using pesticides, insecticides, chemical fertilizers, or other artificial additives, which is a very good thing--especially when compared to the way many other non-organic crops (pineapple, coffee, bananas, etc.) are cultivated in the tropics. It's pretty obvious from our days in the field at Cañas Dulces that no one is applying insecticides to the aloe, which we've seen is a veritable paradise for tiny invertebrates including the White Peacock butterfly, Anartia jatrophae (above), solitary bees, mantids, and one-inch-diameter orb-weaver spiders (below).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center What we'd like to see is small farmers in Guanacaste moving toward the planting of Aloe Vera as a money-making crop--not by clearing and destroying forest growth but by converting existing farm plots to aloe. Guanacaste's nutrient-rich volcanic soil and semi-arid climate is perfect for this plant that requires little care, no additional watering, and is disease- and pest-resistant. Aloe's external leaves can be harvested at least two times each year without damaging the plant and the market is good because the world appears to have an ever-growing demand for products containing aloe--e.g., body lotions, tonics, cosmetics, sunscreens, soaps, even sock yarn!

In other words, Aloe Vera is one of those sought-after "sustainable" products that can be cultivated for long periods--the aloe fields at Cañas Dulces have been producing for nearly 15 years--which could bring long-term revenue to farmers who otherwise have to invest a lot of time, labor, and money to manage crops that are less-environmentally friendly. Our observations confirm that the fields support a wide variety of wildlife, including non-migratory hummingbirds such as the Green-breasted Mango (female, above). Of greater interest to North American birders is that our work has shown aloe plantations provide winter sustenance and/or habitat for Neotropical migrants--some of which are in serious decline. Thus, we're going to do what we can to investigate these possibilities and--if it seems appropriate--to promote planting of Aloe Vera in fields previously used for crops that yield fewer all-around benefits. 2009 SUMMARY REPORT (Part 9) Building upon our five years of successful study of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica, we plan to return to the Guanacaste aloe fields in 2010 with two more groups of citizen scientists. We'll take a third group next year to the Guatemalan plantation of the owner of the Cañas Dulces finca to learn whether ruby-throats and Neotropical migrants are utilizing aloe there in similar ways. And because we've gotten a good tip on RTHU feeding from Cashew tree blossoms at Crooked Tree in northern Belize (see map below), we'll round out the winter season by leading a fourth expedition there. (As with the new Guatemala trip, we're still ironing out details for Belize and will post them to Tropical Hummingbird Expeditions as soon as possible. We've already heard from several Costa Rica trip alumni who expect to go to Belize!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We also hope to collaborate more with Central American natural history groups, as when we visited El Salvador in November 2008 to give a paper at a major biodiversity congress and offer an introductory hummingbird banding workshop for Mesoamerican field biologists. On that trip we handled the first Ruby-throated Hummingbirds ever banded in El Salvador and later went on to Lake Atitlan, Guatemala to capture another 58--also the first to be banded in that country. Our desire is to work with banders in all the Mesoamerican countries, training them to band ruby-throats as we try to gain better understanding of the species' winter and migratory behavior.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center OMEGA NINERS SCRAPBOOK We hope you'll enjoy the following images of people, places, plants, and wildlife, taken during follow-up work by the Omega Niners hummingbird banding expeditions to Costa Rica, February 2009. If you know the names of any organisms we list as "unidentified," please send the ID to INFO.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This tiny Costa Rican songbird--scarcely bigger than a hummingbird--has a name about as long as its body:

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This unidentified white flower and accompanying leaves were beaten badly by the winds that hit Guanacaste Province during early February. Produced by a shrub or small tree, the flower is one of many upon which we observed Ruby-throated Hummingbirds feeding.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ruby-throated Hummingbirds also visited the yellow-orange flower of Gmelina arborea (above), a non-native tree from India that added to our ever-growing list of Costa Rican plants providing nectar for this Neotropical migrant. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the Gamma Niners checked in with their respective airline counters at Liberia and made ready to return home to the U.S. or Canada. (A few folks elected to stay on for extended travel elsewhere in Costa Rica.) After this final airport run, ever-dependable driver Guillermo "Whiskers" Hernandez headed off for San Jose in his bus, accompanied by Elaida "Ela" Villanueva Mayorga (above left), an alumna of our very first hummer expedition in 2004. This year we were glad to have Ela along for Week Three when she provided invaluable assistance as an experienced runner who carefully helped extricate birds from our mist nets.

the Gamma Niners checked in with their respective airline counters at Liberia and made ready to return home to the U.S. or Canada. (A few folks elected to stay on for extended travel elsewhere in Costa Rica.) After this final airport run, ever-dependable driver Guillermo "Whiskers" Hernandez headed off for San Jose in his bus, accompanied by Elaida "Ela" Villanueva Mayorga (above left), an alumna of our very first hummer expedition in 2004. This year we were glad to have Ela along for Week Three when she provided invaluable assistance as an experienced runner who carefully helped extricate birds from our mist nets.  Lingering for a few more days was the two-member Omega Niner group, i.e., Ernesto Carman Jr. (at right, Ela's fiance and the project's in-country guide and co-investigator) and trip leader Bill Hilton Jr. (Operation RubyThroat founder and executive director of Hilton Pond Center). The following report includes a description of their work, a summary of 2009 results, a cumulative look at our first five years of hummer banding research in Costa Rica, and our usual collection of plant and animal photos--including some of newly observed hummingbird nectar flowers.

Lingering for a few more days was the two-member Omega Niner group, i.e., Ernesto Carman Jr. (at right, Ela's fiance and the project's in-country guide and co-investigator) and trip leader Bill Hilton Jr. (Operation RubyThroat founder and executive director of Hilton Pond Center). The following report includes a description of their work, a summary of 2009 results, a cumulative look at our first five years of hummer banding research in Costa Rica, and our usual collection of plant and animal photos--including some of newly observed hummingbird nectar flowers.

Of more emotional interest for trip leader Hilton was his beloved Pittsburgh Steelers would be playing that evening in the Super Bowl and Ernesto had promised to try to find somewhere the big game would be on TV. Folks must understand said trip leader was born in Pittsburgh and since childhood has intently followed (mostly from a geographic distance) the black-and-gold teams--football Steelers, baseball Pirates, and--after their more recent inception, the hockey Penguins. Being Costa Rican, Ernesto doesn't even think what they play in the NFL is truly football, i.e., futbol--the term applied to soccer elsewhere in the world. Nonetheless, with the possibility of actually watching the Super Bowl later that evening--and not just reading about its outcome in week-old newspapers upon returning home--the trip leader excitedly departed Buena Vista Lodge with Ernesto for the ride down to the aloe fields at Cañas Dulces.

Of more emotional interest for trip leader Hilton was his beloved Pittsburgh Steelers would be playing that evening in the Super Bowl and Ernesto had promised to try to find somewhere the big game would be on TV. Folks must understand said trip leader was born in Pittsburgh and since childhood has intently followed (mostly from a geographic distance) the black-and-gold teams--football Steelers, baseball Pirates, and--after their more recent inception, the hockey Penguins. Being Costa Rican, Ernesto doesn't even think what they play in the NFL is truly football, i.e., futbol--the term applied to soccer elsewhere in the world. Nonetheless, with the possibility of actually watching the Super Bowl later that evening--and not just reading about its outcome in week-old newspapers upon returning home--the trip leader excitedly departed Buena Vista Lodge with Ernesto for the ride down to the aloe fields at Cañas Dulces.

1) Eat a big supper; and, 2) Find a place to watch the Pittsburgh Steelers play the Arizona Cardinals in Super Bowl XLIII. As expected, Ernesto came through like a champ by covering both needs at once. Thanks to his sister Tina--staying at an American family's house on Guanacaste's Pacific Coast--we were invited to a food-intense pre-game "tailgate party" and then got to watch the entire game in high-def via satellite from a San Francisco network affiliate. We are ever-grateful for the real-time opportunity to see Ben Rothlisberger connect with Santonio Holmes in the end zone with seconds to play, bringing home to our native Pittsburgh a sixth Super Bowl trophy. Needless to say, our long ride back to Buena Vista Lodge was super-pleasant, and we slept very, very well.

1) Eat a big supper; and, 2) Find a place to watch the Pittsburgh Steelers play the Arizona Cardinals in Super Bowl XLIII. As expected, Ernesto came through like a champ by covering both needs at once. Thanks to his sister Tina--staying at an American family's house on Guanacaste's Pacific Coast--we were invited to a food-intense pre-game "tailgate party" and then got to watch the entire game in high-def via satellite from a San Francisco network affiliate. We are ever-grateful for the real-time opportunity to see Ben Rothlisberger connect with Santonio Holmes in the end zone with seconds to play, bringing home to our native Pittsburgh a sixth Super Bowl trophy. Needless to say, our long ride back to Buena Vista Lodge was super-pleasant, and we slept very, very well.

After bidding fond adieu to our two very-favorite tica and tico friends, our 4.5-hour nonstop flight back to Charlotte was uneventful (but without food or a movie). We cleared customs only upon convincing an officer we most certainly were NOT bringing tropical hummingbirds into the country, nor any of their feathers, eggs, or nests. Met at the airport by wife Susan, we finally went back to Hilton Pond after five weeks away from home--greatly pleased with work done by all our groups in Costa Rica and already setting the calendar for more Operation RubyThroat expeditions to the Neotropics in 2010.

After bidding fond adieu to our two very-favorite tica and tico friends, our 4.5-hour nonstop flight back to Charlotte was uneventful (but without food or a movie). We cleared customs only upon convincing an officer we most certainly were NOT bringing tropical hummingbirds into the country, nor any of their feathers, eggs, or nests. Met at the airport by wife Susan, we finally went back to Hilton Pond after five weeks away from home--greatly pleased with work done by all our groups in Costa Rica and already setting the calendar for more Operation RubyThroat expeditions to the Neotropics in 2010.

Turns out the owner--Alfredo Oliva Véliz--actually lives in Guatemala and only visits Cañas Dulces a few times each year. Alfredo (at right with Bill Hilton Jr.), who spoke English well and was very familiar with our work, was warm and gracious and told us we were always welcome to conduct hummingbird research on his plantation. He also talked about how a few of his fields--especially AV2--had never been very productive, so to generate revenue he had surveyed about 20 acres or so to be sold as residential lots. When we expressed concern for the future of hummingbird research at Cañas Dulces, Alfredo assured us his remaining fields would still be devoted to Aloe Vera and, as such, would continue to provide winter nectaring areas--and a Neotropical study site--for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

Turns out the owner--Alfredo Oliva Véliz--actually lives in Guatemala and only visits Cañas Dulces a few times each year. Alfredo (at right with Bill Hilton Jr.), who spoke English well and was very familiar with our work, was warm and gracious and told us we were always welcome to conduct hummingbird research on his plantation. He also talked about how a few of his fields--especially AV2--had never been very productive, so to generate revenue he had surveyed about 20 acres or so to be sold as residential lots. When we expressed concern for the future of hummingbird research at Cañas Dulces, Alfredo assured us his remaining fields would still be devoted to Aloe Vera and, as such, would continue to provide winter nectaring areas--and a Neotropical study site--for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

This was a significant recapture because it was the very first time any hummingbird banded in the Neotropics had returned to the same locale after migrating to and from North America. As such, this bird was the first to show ruby-throats can have site fidelity on their main wintering grounds just as they do within the breeding range. (Site fidelity for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is well-documented at Hilton Pond Center, where about 12% of those we band return and are recaptured in at least one later year.)

This was a significant recapture because it was the very first time any hummingbird banded in the Neotropics had returned to the same locale after migrating to and from North America. As such, this bird was the first to show ruby-throats can have site fidelity on their main wintering grounds just as they do within the breeding range. (Site fidelity for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds is well-documented at Hilton Pond Center, where about 12% of those we band return and are recaptured in at least one later year.) In 2007 the Lucky Sevens banded just 31 RTHU during five days in the field in AV3, but TWO of their birds were recaptured in 2008. The first was caught by Crazy '08s Alpha in AV3 just one net over from where it had been originally caught. This bird--C51582--had been banded as an after hatch year female, so after last year's returning male, we now knew both sexes of RTHU showed winter site fidelity in the Neotropics. The second recapture in 2008 came through the work of Crazy '08s Omega, which netted C51571 in AV4. This bird had been banded as a fully gorgetted after-second-year male the preceding year and returned as an after-third-year bird.

In 2007 the Lucky Sevens banded just 31 RTHU during five days in the field in AV3, but TWO of their birds were recaptured in 2008. The first was caught by Crazy '08s Alpha in AV3 just one net over from where it had been originally caught. This bird--C51582--had been banded as an after hatch year female, so after last year's returning male, we now knew both sexes of RTHU showed winter site fidelity in the Neotropics. The second recapture in 2008 came through the work of Crazy '08s Omega, which netted C51571 in AV4. This bird had been banded as a fully gorgetted after-second-year male the preceding year and returned as an after-third-year bird. To help us determine how well we are doing at mist netting Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the aloe fields of Costa Rica, we color-mark all our captures with temporary blue dye. We know from experience intense tropical sun causes the dye to fade within a few weeks, so it's unlikely any RTHU we mark in Costa Rica in midwinter will still show signs of blue when returning to North America in spring. (NOTE: All ruby-throats we band at Hilton Pond Center are anointed with green dye, so there is a chance observers elsewhere in the eastern U.S. or southern Canada could spot a green-marked bird we band here.) This year in Costa Rica we had two study sites about ten mile apart,

To help us determine how well we are doing at mist netting Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the aloe fields of Costa Rica, we color-mark all our captures with temporary blue dye. We know from experience intense tropical sun causes the dye to fade within a few weeks, so it's unlikely any RTHU we mark in Costa Rica in midwinter will still show signs of blue when returning to North America in spring. (NOTE: All ruby-throats we band at Hilton Pond Center are anointed with green dye, so there is a chance observers elsewhere in the eastern U.S. or southern Canada could spot a green-marked bird we band here.) This year in Costa Rica we had two study sites about ten mile apart,  so we marked all RTHU from Cañas Dulces with a single horizontal line (above right) and those at the Carrington aloe fields south of Liberia with two lines (below left).

so we marked all RTHU from Cañas Dulces with a single horizontal line (above right) and those at the Carrington aloe fields south of Liberia with two lines (below left).

told a Holbrook travel representative who eventually arranged for us to make our first Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expeditions to Guanacaste Province in the winter of 2004-05. We chose the day after Christmas 2004 as our arrival date, essentially because we wanted teachers still on holiday break to have opportunity to participate. Although our timing worked for educators, it was NOT a good time to try to band Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--mostly because that time of year was apparently too early for Aloe Vera to be blooming. Fortunately, we did find a small population of ruby-throats feeding on Jocote tree flowers (above right) and were able to band 15 of them with two groups that first year.

told a Holbrook travel representative who eventually arranged for us to make our first Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expeditions to Guanacaste Province in the winter of 2004-05. We chose the day after Christmas 2004 as our arrival date, essentially because we wanted teachers still on holiday break to have opportunity to participate. Although our timing worked for educators, it was NOT a good time to try to band Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--mostly because that time of year was apparently too early for Aloe Vera to be blooming. Fortunately, we did find a small population of ruby-throats feeding on Jocote tree flowers (above right) and were able to band 15 of them with two groups that first year. Among the aloe we caught 51 birds but no adult males, which we assumed had already started moving back north in spring migration. To avoid this phenomenon in 2007 we decided upon early February as our start date and, as anticipated, the aloe was blooming AND we caught some adult males, although fewer than expected. Attempting to fine-tune the best time to study and band all ages and sexes of ruby-throats in Guanacaste, in 2008 we took our two groups in late January and early February, when the aloe was blooming AND we had our most productive banding season to date.

Among the aloe we caught 51 birds but no adult males, which we assumed had already started moving back north in spring migration. To avoid this phenomenon in 2007 we decided upon early February as our start date and, as anticipated, the aloe was blooming AND we caught some adult males, although fewer than expected. Attempting to fine-tune the best time to study and band all ages and sexes of ruby-throats in Guanacaste, in 2008 we took our two groups in late January and early February, when the aloe was blooming AND we had our most productive banding season to date. Within Guanacaste Province in Costa Rica, aloe is exposed to a predictable annual rainy season that roughly corresponds to "summer" in North America (actually late spring through late fall). Our "winter" more or less coincides with Costa Rica's equally predictable dry season, which occurs annually from about November through March.

Within Guanacaste Province in Costa Rica, aloe is exposed to a predictable annual rainy season that roughly corresponds to "summer" in North America (actually late spring through late fall). Our "winter" more or less coincides with Costa Rica's equally predictable dry season, which occurs annually from about November through March.

In the meantime we'll be starting on some papers for professional journals, plus traveling to our native Pittsburgh on Easter weekend 2009 for a presentation at the joint meeting of the Wilson Ornithological Society and Association of Field Ornithologists. Afterwards, we'll get to take in the home opener at PNC Park for our beloved Pittsburgh Pirates. Hummingbirds in the tropics and spring baseball in the Steel City. What more could one want?

In the meantime we'll be starting on some papers for professional journals, plus traveling to our native Pittsburgh on Easter weekend 2009 for a presentation at the joint meeting of the Wilson Ornithological Society and Association of Field Ornithologists. Afterwards, we'll get to take in the home opener at PNC Park for our beloved Pittsburgh Pirates. Hummingbirds in the tropics and spring baseball in the Steel City. What more could one want?