|

|

|||

|

(Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

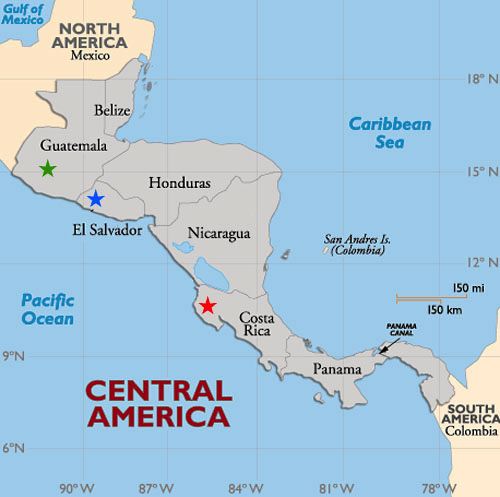

BELIZE-ONEERS AT CROOKED TREE: During the past six years our Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Costa Rica have been highly successful as the only on-going systematic attempts to study Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) on the southern end of their migratory path. These tiny Neotropical migrants breed in the eastern U.S. and southern Canada--where ornithologists have studied them literally for centuries--and nearly all fly to Mexico of Central America for the winter. Since 2004 we've taken ten groups of "citizen scientists"--teachers, backyard birders, and hummingbird enthusiasts--into Guanacaste (red star on map below), the dry western province of Costa Rica where RTHU spend the OTHER six months of their lives. We've learned a lot about ruby-throat behavioral ecology on their Costa Rican wintering grounds and have banded an unprecedented 657 individuals in Guanacaste, seven of which have returned in a later year. One even showed up far to the north just west of Savannah GA six months after banding--the first hummer of ANY species banded in the tropics and encountered again on North American breeding grounds.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center Independent of our citizen science groups we also banded the first 57 RTHU for Guatemala (green star on map above) and the first two for El Salvador (blue star), thus expanding our investigations into other Central American countries. We've always wondered, however, about the presence of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Belize--that tiny English-speaking country on the eastern shores of the Yucatan Peninsula. Conventional wisdom says few RTHU winter in Belize but that they move through on their way north in spring, so last summer Hilton Pond Center announced an Operation RubyThroat trip to Belize for March 2010. We were pleased the trip filled quickly--and that ten of the 13 participants were alumni of one of our previous Costa Rica expeditions! After that it was simply a matter of sitting back and waiting for March to roll around. Below is our account of this year's first-ever intensive investigation of ruby-throats in Belize, complete with banding results and extensive photos of some of our amazing experiences during the trip.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center BELIZE BACKGROUND INFORMATION Ever since we started working on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Costa Rica we've sent periodic notices to various listservs asking if folks knew about other RTHU concentrations in Central America. Carol Anderson responded a few years ago that ruby-throats were at her place on the shores of Lake Atitlan in Guatemala, hence our trip there in November 2008. Occasionally we'd get a note from someone in Belize, including one from Nick Bayly--a British ornithologist we worked with while training Colombian banders on San Andres Island back in October 2005. Nick and Camila Gómez Montes had banded extensively in northeastern Belize where they encountered a few migrant ruby-throats in late March, but--more important--Nick's network of birding contacts proved invaluable when he heard from Kevin Loughlin. Kevin, who runs Wildside Nature Tours out of King-of-Prussia PA, e-mailed Nick last February with the message that "Crooked Tree in Belize, with its many Cashew trees, has been an area where we consistently see a large number of ruby-throats." Our further correspondence with Kevin indicated the Cashews were in peak bloom in early to mid-March, which is all the incentive we needed to contact Debbie Sturdivant at Holbrook Travel about setting up our Belize expedition for March 2010.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center Going to a new place--especially with the precise goal of trying to catch, band, and study a single bird species--is a big gamble, especially when you're recruiting folks a year in advance to underwrite the trip and help with field work. We gambled in December 2004 on our first trip to Costa Rica with the Pioneers and came up a little short when Aloe Vera fields were not flowering so early in the season. That winter we still banded 15 RTHU, however, and the next year went back instead in late February to catch 51 hummers among late-blooming aloe. This time around we were betting the Cashew trees (above) would be flowering "on schedule" AND that ruby-throats would be feeding on them. Even with such risk ten of our Operation RubyThroat veterans from Costa Rica signed up without hesitation, eager like us to try catching hummers in a new and very different locale.

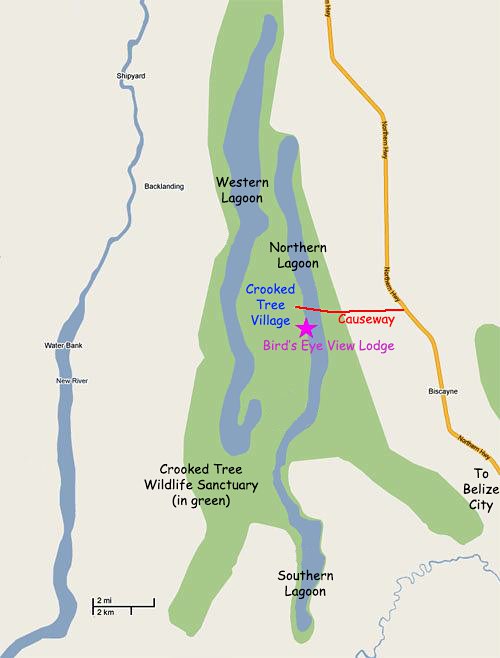

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center Crooked Tree, essentially an island surrounded by two lagoons (see map above and photo below right), is internationally famous as a Belizean wetland attracting huge numbers of wading birds that become more concentrated as the dry season progresses; lack of rain cause the lagoons to grow ever smaller and shallower, and the fish get easier and easier for birds to catch. PRELIMINARY WORK (4-5 March), Omega Group:

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center After six months of thinking about our trip to Belize, we finally departed very early on 4 March from Charlotte, survived a short layover in Miami, and took our remaining two-hour flight to Goldson International Airport in Belize City. There we were met by Leonard Gillett,

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center Directly in front of the lodge--across a 150-yard expanse of flat freshwater--was a grassy island covered with perhaps the densest assemblage of wading birds we'd ever seen (above, with closer views provided below). The bigger birds were Wood Storks, Great Egrets, and Great Blue Herons but we also could make out somewhat smaller Tri-colored Herons, Little Blue Herons, White Ibises, and even a couple of Roseate Spoonbills. Beyond them were Neotropical Cormorants and rafts of Black-bellied Whistling-Ducks, with a few Fulvous Whistling-Ducks scattered throughout. Northern Jaçanas hopped around on fallen reeds while American Coots splashed about and Pied-billed Grebes dived in and out of sight. And, standing tall among all the other birds, were several of those elusive Jabiru--birds we had seen only once before at a freshwater shrimp farm west of Liberia in Costa Rica. Based on this initial panorama we knew already everyone in our group was really going to enjoy this year's expedition to Belize.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center

Despite picturesque views and the abundance of wading birds, our main reason for being at Crooked Tree was to observe Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, so on the morning of 5 March we set off unaccompanied and on foot to scout the area for potential study sites. It was hard to get far because power lines and trees along the dirt road leading inland from the lodge were adorned with all sorts of resident birds, from a Great Kiskadee (above) with insect entrails on its bill to a hyperactive male Vermilion Flycatcher (below) in pursuit of food for his chicks.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center A little further along we had our first intimate encounter with a Cashew tree, a small one overhanging the road. It was covered with tiny, half-inch green and reddish blossoms that emanated a sweetish but not strong odor. We decided to step back a bit to watch the tree for activity; surprisingly, there were no bees or flies or wasps coming to what appeared to be an abundant nectar source.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eventually, after about 15 minutes or so, a probable pollinator finally showed up and we zeroed in on it through our fully extended 100-400mm Canon telephoto lens. There wasn't much doubt we already had found the object of our quest (above)--a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird flitting about and probing Cashew flower after Cashew flower with her bill. We photographed and watched this bird for a while until she chased off a second RTHU that got too close to the nectar tree. This was all very good news, of course, because the following day our 13 trip participants were due to show up from across the U.S. to study Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Apparently, Kevin Loughlin had advised us well when he told us we could find ruby-throats feeding from Crooked Tree's Cashew blossoms in early March.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center With this satisfying news in mind, we wandered further along one of the many trails established on the island by Belize Audubon Society, watching and photographing such birds as a Tropical Mockingbird in a palm tree (above). Eventually we ended up back at Bird's Eye View Lodge in time for lunch--a mouth-watering buffet that included baked Tilapia that had been caught just a few hours earlier in the lagoon. We quickly understood why people rave about Creole-style cooking.

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center That afternoon we noted the management had been maintaining a few hummingbird feeders at the lodge--always a good sign--so we added four more to the backyard garden. During a half-hour of observations we saw mostly Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds (above) coming to sugar water but there was also a male Green-breasted Mango and--even better news--at least one female Ruby-throated Hummingbird that might be a candidate for trapping after expedition participants arrived on the morrow.

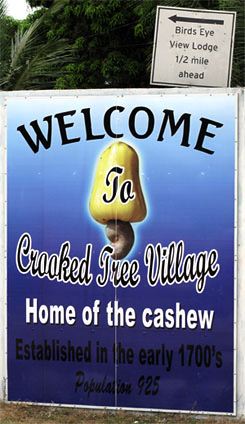

All text, maps, tables & photos © Hilton Pond Center ARRIVAL DAY (6 March): On the morning of 6 March all four nature guides from Bird's Eye View Lodge got together to talk about places around Crooked Tree where they had seen good numbers of ruby-throats in recent days and past years. One of them, 20-year-old Michael Gillett, had a sharp eye for such things and volunteered to drive us around some of the back roads we hadn't explored on foot. Based on the guides' recommendations and our own same-day observations, we settled on what appeared to be a good place to run mist nets. Later on we joined Michael on a run to the airport in Belize City (above), where we met up with all 13 team members--none of whom lost any luggage en route to Belize! After greeting our "old-timers" and meeting the newbies it was off to Crooked Tree and the lodge (sign, with Jabiru, at right), where the group had time to check into their rooms and take a look at that same stunning lagoon view we had experienced on our first day. Then, after supper--complete with a complimentary serving of Cashew wine--everyone gathered on the lodge's upstairs patio for a presentation about our past work on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the Neotropics--including archival photos of the ten alumni who had gone with us to Costa Rica in years past. As is our tradition, we also announced the group's nickname. Partly to honor the "Pioneers" who first accompanied us to Guanacaste, we decreed these adventuresome travelers would be called the "Belize-Oneers." Corny perhaps, but we thought it appropriate. Joining us in Belize for 2010 were Costa Rica veterans Anne Beckwith (Durham NC, Krazy '08s Omega); Elisabeth Curtis (Carrboro NC, Lucky Sevens); Mary Kimberly & Gavin MacDonald (Decatur GA, Gamma Niners); Liz Layton (Washington DC, Alpha Niners); Kathy Roggencamp (Carrboro NC, Krazy '08s Omega); Ann-Marie Rutkowski (Rotterdam NY, Alpha Niners); Lisa Schuermann (Charlotte NC, Pioneers); and Gail & Tom Walder (Wilson NY, Crazy '08s Alpha). We were pleased most past expeditions were represented and welcomed three "newbies" to our midst: Mindy Hetrick (Wheat Ridge CO); Judy Lyons (Louisville KY); and Sherry Skipper (Golden CO). What a splendid group! |

Most of the island is under protection of the Belize Forest Service and Belize Audubon Society, both of which granted permission for our hummingbird research. Debbie Sturdivant was familiar with Crooked Tree, having visited the area a few years ago to scout locations for Holbrook's education trips, so she booked us into Bird's Eye View Lodge (pink star on map above, BEVL for short). We read that BEVL--situated right on the west shore of the Northern Lagoon--would offer our group breathtaking views of thousands of herons, egrets, ducks, and other water birds, plus the area's largest and most sought-after bird--the giant Jabiru stork. We couldn't wait to get to Crooked Tree to find out if all this could really be true.

Most of the island is under protection of the Belize Forest Service and Belize Audubon Society, both of which granted permission for our hummingbird research. Debbie Sturdivant was familiar with Crooked Tree, having visited the area a few years ago to scout locations for Holbrook's education trips, so she booked us into Bird's Eye View Lodge (pink star on map above, BEVL for short). We read that BEVL--situated right on the west shore of the Northern Lagoon--would offer our group breathtaking views of thousands of herons, egrets, ducks, and other water birds, plus the area's largest and most sought-after bird--the giant Jabiru stork. We couldn't wait to get to Crooked Tree to find out if all this could really be true.

BEVL's knowledgeable head guide and a truly gracious man who drove us literally all over Belize City so we could pay our research permit fee and in pursuit of ten sets of metal mist net poles and iron rebar for anchoring them in the ground. With 20 ten-foot electrical conduit sections and eight even-more-unwieldy ten-foot pieces of rebar loaded in the van, Leonard took us up the Northern Highway to Crooked Tree with the promise he would personally hacksaw the rebar into 2.5-foot lengths for us to use in the field. (And he eventually did, for which we were grateful.) About an hour later we arrived at Bird's Eye View Lodge (above), were greeted warmly by hotel manager Verna Gillett Samuels and her personable, professional daughter/assistant Kisha Samuels. (Bird's Eye View Lodge is very much a family affair, and they made US feel like family!) We checked into our non-smoking room--recently refurbished with shiny new tile on floor and wall and complete with comfy bed, air conditioning, and dependable hot shower--and immediately grabbed our binoculars for a peek at what might be on the lagoon. In all honesty, we were stunned and thrilled at what we saw.

BEVL's knowledgeable head guide and a truly gracious man who drove us literally all over Belize City so we could pay our research permit fee and in pursuit of ten sets of metal mist net poles and iron rebar for anchoring them in the ground. With 20 ten-foot electrical conduit sections and eight even-more-unwieldy ten-foot pieces of rebar loaded in the van, Leonard took us up the Northern Highway to Crooked Tree with the promise he would personally hacksaw the rebar into 2.5-foot lengths for us to use in the field. (And he eventually did, for which we were grateful.) About an hour later we arrived at Bird's Eye View Lodge (above), were greeted warmly by hotel manager Verna Gillett Samuels and her personable, professional daughter/assistant Kisha Samuels. (Bird's Eye View Lodge is very much a family affair, and they made US feel like family!) We checked into our non-smoking room--recently refurbished with shiny new tile on floor and wall and complete with comfy bed, air conditioning, and dependable hot shower--and immediately grabbed our binoculars for a peek at what might be on the lagoon. In all honesty, we were stunned and thrilled at what we saw.