|

|

|||

|

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND

19-28 February 2011 INSTALLMENT #504---Visitor # (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

|

THE HUMMINGBIRD ADVENTURE • PREFACE • As noted in last week's photo essay, our 11th Operation RubyThroat hummingbird banding expedition to Costa Rica that began in late January 2011 encountered an unexpected major snag when we got to our primary study site in Guanacaste Province: An entire Aloe Vera plantation where we'd banded nearly 600 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds had been purchased and converted into grassland destined for cattle. This was quite a shock because it meant there was no hope at that 500-acre locale of collecting any future data about site fidelity in ruby-throats that breed in the eastern U.S. and southern Canada before migrating to spend winter months in Mexico and Central America. Not to be deterred, however, Th'Levens--the nickname we bestowed on this year's eight-person citizen science group that journeyed with us as field assistants--rose to the challenge and at alternate sites near Liberia helped catch and band 105 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, bringing our seven-year total for Costa Rica to 727. We had several other setbacks in Costa Rica during the nine-day expedition, including our purloined iPhone 4 and broken digital projector--both of which needed to be replaced when we returned to Hilton Pond Center for a four-day break. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center • ADVANCE TEAM ARRIVAL • Our 2011 expedition to Guatemala began on 19 February when the advance team (trip leader Bill Hilton Jr. & expert guide/interpreter Ernesto Carman Jr.) flew from their respective airports (Charlotte, North Carolina & San Jose, Costa Rica) into Guatemala City (see map above), where they were met by Hugo the cab driver. Hugo then drove us all over the capital looking for a hardware store that carried rebars and 10' EMT steel tubing needed for mist net poles, stopping for lunch at--what else in the tropics?--the local Taco Bell. Alas, it was Saturday afternoon and most stores were closed--plus downtown was extremely crowded by hundreds of brightly colored buses that brought thousands of folks to town for a big political rally. We never located any tubing but did find a store that cut rebar into three-foot lengths we could use as anchors to hold net poles in place if we happened to acquire some. We also finally found our long-lost bus driver--Alex Figueroa--who had to add two hours to his five-hour drive from Honduras because a bridge was out. After transferring our luggage, field gear, and newly purchased rebar from cab to bus the advance team began its two-hour journey northeast to Casa Guastatoya--the hotel that was to serve as home base when the rest of the team arrived from the U.S.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our hotel was right on a main square in Guastatoya that appeared to be the center of the universe for people of all ages; each evening local folks made countless trips around the square on motorbikes and in assorted other vehicles from farm trucks to pickups to those ubiquitous "tuk-tuks"--a sort of covered three-wheeled motorcycle (above) whose seemingly ceaseless horn toots give the tuk-tuk its name. Most cars were outfitted with super-bass sound systems and a few even had loudspeakers mounted on their roofs! That first night we were witness to this Guatemalan version of cruising from supper until well after 10 p.m., at which time we had to crank up the hotel room air conditioner until it was loud enough to drown out street noise.

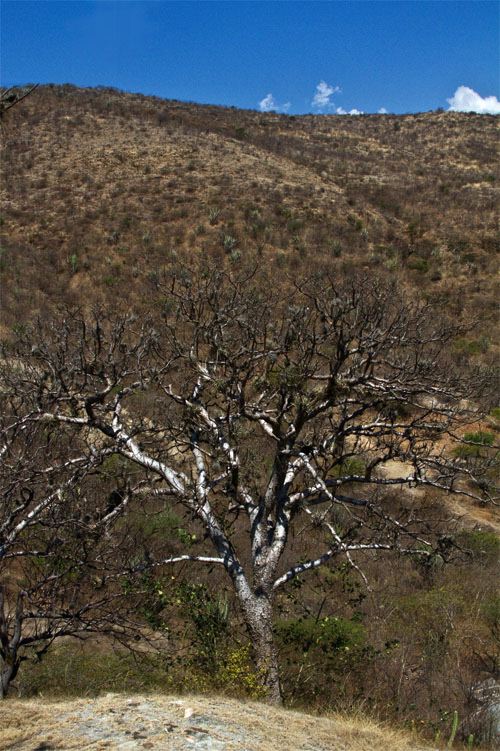

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY ONE • Next morning we rose at dawn for breakfast and a drive to Alfredo's aloe farm about six miles southwest of the hotel. Alfredo was kind enough to transport us in his personal car, which turned out to be a good idea; the first two miles were on blacktop but the remaining route followed amazingly steep and bumpy and dusty dirt roads that would have taken a bus twice as long to traverse. As we drove down a steep slope we observed the surrounding land was VERY dry--more so than we had anticipated even though Guatemala was in the midst of its annual dry season. Alfredo explained the surrounding habitat was deciduous "dry thorn forest" (above) and that the Motagua Valley that includes Guastatoya is reportedly the driest place in Central America!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We went past the small Mayan town of Subinal and continued on to the bottom of the hill where a live stream provided water that helped non-deciduous vegetation remain lush and green. Crossing a bridge over the waterway we passed through a grove of limon verde (limes)--a crop that supplemented Alfredo's aloe-based income. We eagerly anticipated what we knew as just ahead--the aloe plantation whose nectar would attract lots of hummingbirds--but were dumbstruck by what we actually saw: 400 acres of aloe spread out before us in a beautiful landscape (above), but--with a mere handful of exceptions--the aloe plants were NOT in bloom! This tableau was eerily reminiscent of our first trip to Costa Rica in December 2004 when we got to the aloe farm at Cañas Dulces BEFORE the aloe had flowered. This time, Alfredo explained, plants weren't in bloom because Guastatoya's dry season had come early and virtually all the cultivated and native flora in the valley had already blossomed. In other words, we were six weeks LATE! It goes without saying we were completely stunned that neither nectar-bearing flowers nor nectar-eating hummingbirds were anywhere to be seen. Alfredo, gracious host that he was, apologized profusely that we had come so far to band Ruby-throated Hummingbirds among the aloe and wouldn't be able to do so. We assured him we knew it was not his fault but that of strange weather (and maybe even what some folks call "global warming").

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We spent the next hour touring Alfredo's lovely but flower-less aloe plantation, cursing our luck the whole time. We eventually did see a Canivet's Emerald and one lonely Ruby-throated Hummingbird--an apparent female (above) that Ernesto was able to photograph as a sad record of what may have been the only RTHU still around. She sat there a long time, perhaps pondering the whereabouts of nectar-laden yellow flower stalks that not too long ago had sprung from each of Alfredo's millions of aloe plants. On the way back up the mountain we complimented Alfredo on a well-managed aloe farm but wondered how our incoming group from North America would respond when they, too, saw that Ruby-throated Hummingbirds would NOT be concentrated among the aloe and available for banding.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center With all this in mind the advance team returned to the hotel, boarded Alex's air conditioned bus, and headed back toward Guatemala City to meet the rest of the group. We didn't get far out of Guastatoya before Alex realized we had a flat front tire that needed to be fixed; fortunately, Alex (at left above) and a worker at a roadside wheel repair shop were able to manhandle the tire and put in a new tube that made everything almost good as new, avoiding what would have been a real problem had the flat occurred in the Guatemalan wilderness. Arriving at Guatemala City airport a couple of hours later we waited impatiently for flights to land and our cadre of volunteers to clear customs and immigration.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Happily, by mid afternoon we had our complete 2011 Guatemala crew, six of whom were alumni from previous Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expeditions: Pat Barker (Charleston WV, alum of Costa Rica 2010), Anne Beckwith (Durham NC, CR2008 & Belize 2010), Lin Gossman (Chicago IL), Mary Kimberly & Gavin MacDonald (Decatur GA, CR2009 & BE2010), Brenda Piper (Middleton MA, CR2010), Kathy Roggenkamp (Carrboro NC, CR2008 & BE2010) & Warren Shuck (Stoughton WI). After a snack at the airport cafe we were off to Casa Guastatoya for check-in, supper, and an evening orientation meeting. In his self-assumed but welcome role as in-country host, Alfredo had arranged for us to meet in a very nice open-air assembly area a few blocks away. Then it was back to the hotel and snooze time for everyone--but only after we all cranked up our in-room air conditioning units to drown out the multitude of Saturday night celebrants cruising past our bedrooms.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY TWO • We were up bright and early on 21 February, with Casa Guastatoya's friendly restaurant staff serving a tasty buffet breakfast at 6 a.m. Especially helpful was Sandy (below left), a young Guatemalan woman who made us feel right at home with her smile and pleasant demeanor.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Guastatoya region was in the middle of a drier-than-usual dry season, and dust covered many plants. As inhabitants of Guatemala's dry thorn forest, various trees and shrubs were armed with a diversity of spines, prickles, and thorns, and we were not surprised to see cacti (Opuntia sp., above) and other succulents growing in the arid soil. When we arrived at the entry to Alfredo's finca, there was an abrupt change in vegetation--mosty because of that small river and irrigation techniques that allowed limes trees to prosper. The participants remarked that this looked like it would be a good place to watch hummingbirds but when they passed through the lime grove and entered the aloe plantation they were as stunned as the advance team had been the day before. "Where are the aloe flowers?" was the universal question, and we had no choice but to admit to the group we had missed the much-earlier-than-usual aloe bloom period by about six weeks. Our team members knew immediately the seriousness of our dilemma; Without aloe flowers to concentrate the hummers it would be almost impossible to catch them in either mist nets or traps.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We spent the first hour or so driving around the 400-acre farm looking for hummers and aloe flowers and found none of the former and precious few of the latter. There were occasional clumps of aloe with a flower stalk or two (above), but for the most part our chances of banding ruby-throats at this locale seemed more than dismal.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ever optimistic, however, the group spent some time talking about our alternatives, one of which was to explore the interface between lime grove and aloe field to see if a few hummers might still be around. That strategy also ended up fruitless, so the next plan was to walk through the dry forest paralleling the stream to see if ruby-throats might be hanging out in that habitat. Alas, all we found was even more spiny vegetation (unidentified tree, above) that gives the dry thorn forest its name.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center To be honest, we did see a few hummers--Rufous-tailed and Cinnamon--but no ruby-throats, and there were some other "good birds" for the group to watch. Ernesto was adept, as always, at finding birds in the scrub and at showing them to the group through binoculars and his ever-ready spotting scope (above). Although such birdwatching was fun, our main reason for coming all this way was to observe, capture, and band Ruby-throated Hummingbirds; we desperately needed a back-up plan, so after returning to Casa Guastatoya we called Holbrook Travel's representatives with a suggestion: Move the entire expedition from the aloe fields of bone-dry Guastatoya to the other side of Guatemala where we had been told ruby-throats were coming to feeders at a lodge in much lusher habitat. Holbrook reps took this suggestion as a challenge and told us they'd see what they could do on short notice.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY THREE • There was little we could do hummingbird-wise in Guastatoya while we waited for Holbrook to facilitate an alternative, so on 22 February we altered our schedule to include a bus trip to the nearby towns of San Agustín & San Cristóbal Acasaguastlán, homes to two churches established long ago by Spanish priests and missionaries. For this excursion the local police chief insisted on providing a vehicular escort that included three officers, one heavily armed with an automatic rifle (see truck at left in photo of San Agustín's ornate church, above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although most Guatemalans we encountered were friendly, the police chief admitted there were ne'er-do-wells who might prey upon a tour bus full of gringos while admiring the ornate interior of the church at San Cristóbal Acasaguastlán (above). He also chided us for going unattended to Alfredo's aloe farm the previous day and suggested we not take any more trips without requesting a police escort. (We should have listened more carefully.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center After our visits to the two churches we headed back toward Guastatoya but were curious about another place on the map, so we turned north on a less travelled road--shadowed, of course, by our police escort. Our new destination was Guaytán, an oft-overlooked national archaeological site.

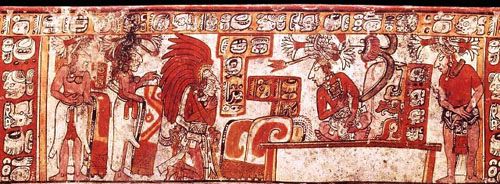

Vase image courtesy AuthenticMaya.com Some Guaytán artifacts were remarkably well-rendered, such as the panoramic exterior of a polychrome vase (above); it supposedly depicts a palace scene. Incidentally, getting to Guaytán's tombs involved a heart-pounding climb up steep steps in hot sun, but our friendly Guatemalan policemen in their black uniforms and bulletproof vests made the ascent with us, stopping occasionally to wipe their brows, check their firearms, and scan the trail behind and ahead.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Upon our return from the morning trip to churches and the archaeological site, we had lunch in the modest restaurant at Casa Guastatoya (above)--including chocolate covered bananas that quickly became our favorite Guatemalan dessert. We also learned Holbrook's personnel had been hard at work and had ironed out logistics for us to move our hummingbird studies to a new venue at Los Tarrales Reserve about five hours west. We should have liked to continue on in Guastatoya, but with few flowers and almost no Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Alfredo's aloe fields it made little sense to stay. As always, we had given a nickname to this year's citizen scientist volunteers; based on our location and the dearth of hummers, we dubbed them the "GuateNaughts"--a temporary epithet everyone hoped would be updated if our hummer-banding productivity improved.

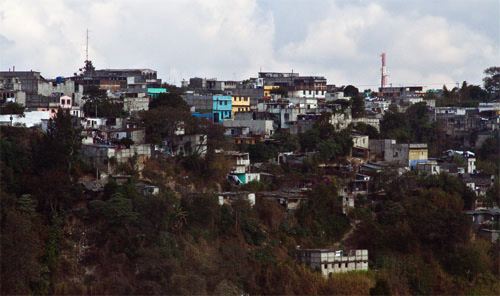

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY FOUR • On the morning of 23 February the GuateNaughts checked out of Casa Guastatoya, boarded Alex's newly washed bus, and turned west on the main highway back toward Guatemala City. As we drove through that mega-metropolis of nearly 3 million people, we were struck by the juxtaposition of beautiful mountain scenery, modern infrastructure, and abject poverty with large numbers of people crowded into substandard hillside housing (above). We were also surprised to see outside every 24-hour teller, car dealership, and appliance store a security guard whose arms cradled an automatic weapon. This was a bit of a shock and something we don't often see back in the U.S., but we imagine the guards' presence serves as an very effective preventive measure against theft and vandalism.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center It took us two hours to get to Guatemala City and another hour to drive through, so we anticipated we would be at our Los Tarrales destination in another two hours (see revised map above). However, a couple of things interfered. For one, we got hungry and we needed baños, so in early afternoon we spotted a pleasant-looking open air restaurant and pulled in to the parking lot for food and relief. The passengers stepped out of the bus, stretched, and made their way to the tables for lunch, which were guarded by--you guessed it--a man with an automatic weapon.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Large aquaria filled with live tilapia (above) guaranteed fresh fish if we so desired, and that's what a few people ordered. While we waited for our meals to arrive a white car pulled into the parking lot on the blind side of the bus and a few minutes later made a speedy exit. This event got special attention from our driver, Alex, who suddenly jumped up, ran to the bus, examined its exterior, and drove off in the direction from which we had just come. Assuming Alex was merely getting gas, no one thought much of the situation until after we had finished our meal, departed the restaurant, and noticed that suspicious white car was following the bus. It turns out someone from the car had spiked Alex's bus tire with a sharp object and undoubtedly intended to commit some nefarious act, perhaps holding up and robbing us passengers when we had to stop to fix a flat. Fortunately, Alex had been observant and had slipped away to get the tire fixed, thereby thwarting the evil intentions of the hoodlums in the white car. It was then we understood the police chief back in Guastatoya hadn't been overly cautious in advising us to have a security escort in certain parts of Guatemala!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It turns out the restaurant was only about 30 minutes away from our destination, so after lunch we looked forward to an afternoon exploration of our new site. Unfortunately, just a few miles from that destination we came upon a line of stopped vehicles and wondered how there could be a traffic jam on this remote road. Alex found out there was another route we could take, so we turned around, drove back about ten miles and then took the alternate route. Once again, as we approached our destination a line of cars and trucks were in the way. It turns out local citizens were holding a demonstration to voice grievances and demand a meeting with the mayor. To make their point perfectly clear they had piled up old tires in the middle of a major intersection and set them ablaze (above). Flames and black smoke billowed skyward, and there was no way we could get through. Our group just sat tight for a couple of hours, hopeful the protestors would disband--especially since a number of armed police had begin arriving. As darkness approached, we decided we should return to a place of greater comfort and headed back toward the restaurant. Almost as soon as we got there we received word the protest was over; Both tired and relieved, the GuateNaughts were welcomed by Los Tarrales administrator Andy Burge (above right), had supper and an evening meeting, and then went off to bed--where we dreamed (ever hopeful) that our run of strange happenings was over and that we could finally get to work banding hummingbirds on the morrow. (NOTE: Despite some usual occurrences during the first part of our Guatemala 2011 expedition, we intend to take future groups to this beautiful country--albeit not to Guastatoya, a rural and sometimes unruly province. Instead we will concentrate on Lake Atitlán, where trip leader Hilton took a highly successful exploratory solo trip in November 2008. There, near the mile-high lakeside village of San Pedro, he captured 56 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in less than a week--the first RTHU ever banded in that country. This idyllic and picturesque region of the Guatemala is a safe and popular tourist destination where much is to be learned about wintering ruby-throats.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY FIVE • We had come to Los Tarrales because several sources had told us this private reserve hosted a winter population of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, and that staff members and local residents maintained hummer feeders. The site--on the south slopes of the Atitlán Volcano--is an old colonial plantation fashioned into a sustainable community that produces coffee, ornamental plants, honey, and other products. It wasn't all that far from San Pedro la Laguna, a small town on the other side of the volcanic ridge where we had spent a week in November 2009 on the shores of Lake Atitlán, capturing the first ruby-throats ever banded in Guatemala. We weren't sure how many RTHU we might find at Los Tarrales, but we figured it had to be more than we saw back in Guastatoya. Besides, local scenery was terrific, including the morning view of Atitlan Volcano itself (above)--complete with scars made years ago when government forces fired rockets to break up insurrectionist guerilla encampments.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Andy, our host, welcomed us again on the morning of 24 February and offered some good news: We could use the Reserve's two four-wheel-drive vehicles to shuttle the GuateNaughts partway up the volcano to a locale where sugar water feeders supposedly were attracting ruby-throats. We were grateful for the cars but had second thoughts when we found out the trip was over an incredibly rough 3.5-mile road that took 45 minutes to navigate. Having been through unusual diversities, however, the GuateNaughts took the challenge of a mere bumpy roadway in stride. Along with our binoculars and other gear, we loaded a set of bamboo poles (above)--Alfredo had provided them back in Guastatoya--in the hope we'd be able to run mist nets when we got up to the field station on the volcano.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Interestingly, the name of the field station on the volcano was Vesuvio, which was at about 4,500' elevation. There was a permanent building that provided a place out of the tropical sun and that could serve as a banding station. The site also allowed killer sunrise views of still more volcanos on the horizon (above), one of which rumbled loudly in the distance and belched smoke several times each day. Most important, there were several hummingbird feeders containing fresh sugar water, so the GuateNaughts hopeful we could finally achieve our 2011 goal of banding ruby-throats in Guatemala.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The crew set up several mist nets in the grassy areas around the building (above) and moved all the feeders into portable hummer traps we had brought from the U.S. Then it was simply a matter of sitting back to see what we might capture. This was not idle time, however, because we also made observations about what plants were in flower--as in Guastatoya, not much was blooming because of the early dry season--and about other species of birds in the vicinity. There was lots of activity around the hummingbird feeders, but not from ruby-throats; instead we heard the incredibly loud wing beats of really big hummers such as Violet Sabrewings.

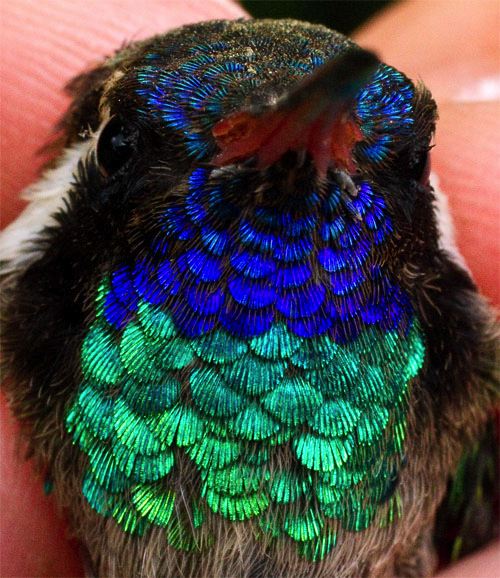

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of Violet Sabrewings, it wasn't too long until we had snared a male of this species in one of our nets. It was a resident bird--not a Neotropical migrant--so we wouldn't be applying a band to its leg, but we did take a close look at its long decurved bill and brilliantly iridescent plumage (above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sabrewings--we also later caught the slightly smaller Rufous Sabrewing--are so-called because of their stout primary feathers (above). In males the vanes of the lead primaries are much reduced and the shaft (rachis) is very wide and thick. The Violet Sabrewing is a BIG six-inch-long hummingbird--the largest hummer species outside South America--and he could probably give a person a substantial judo chop if he so chose.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Within a few minutes of capturing, photographing, and releasing the Violet Sabrewing, we netted two other hummers that were smaller but had even brighter iridescence. These looked very much alike but were actually two different species: Blue-tailed Hummingbird (above) and Berylline Hummingbird.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Adult males both have red lower mandibles and bright green bodies and are so similar one has to look at the rectrices to differentiate them. The Berylline has brownish tail feathers and undertail coverts (above right) and the Blue-tailed sports rectrices (above left) in a dark hue that gives the species its common name.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly after we had puzzled through the Berylline and Blue-tailed hummingbirds another big hummer hit the net, this time one of those Rufous Sabrewings we mentioned earlier. In addition to being a bit smaller than Violet Sabrewings and having a straighter bill, this species also differs in that it is sexually monomorphic--males and females look alike--wheareas its larger relative is dimorphic with the female being far paler and nearly lacking in iridescent purple plumage. By mid-morning at Vesuvio we already had netted four kinds of hummers but they weren't our target species, the Ruby-throated Hummingbird. In fact, we hadn't even SEEN any ruby-throats for sure until late morning when keen-eyed Kathy Roggenkamp, a veteran of our Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Costa Rica and Belize, finally found one perched in a distant tree. (In an official ceremony, Kathy received the highly coveted "Magic Hummingbird Coin" for being the first GuateNaught to confirm identity of a free-flying RTHU.) Within minutes we netted a female RTHU--possibly the same bird spotted by Kathy--and had it in-hand at the banding table. At last we thought we might have cause to change the nickname of the GauteNaughts to something else, but such was not the case. As we attempted to band the newly captured ruby-throat she had other ideas. She twisted and squirmed and slipped from the paper tube in which we had restrained her temporarily, speeding to freedom without any numbered jewelry on her leg. The 2011 Neotropical Jinx--which began back in January in Costa Rica with the loss of an entire banding site--seemed to be continuing! Undaunted, the GuateNaughts shook off this latest setback and vowed we would capture AND band another ruby-throat when we returned the following day.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY SIX • On 25 February it was back to Vesuvio to deploy nets and traps in yet another attempt to capture at least one Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Even though our portable traps contained feeders filled with fresh sugar water, no hummers ever entered them, but the nets continued to snare several kinds of birds--both residents and Neotropical migrants. Of the latter, our most commonly captured species was a drab little bird from North America that I had never handled back home: The sexually monomorphic Warbling Vireo (above).

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center While we waited anxiously for those elusive ruby-throats to hit the nets, we captured still more hummer species. Next up was an immature Magnificent Hummingbird (above and below), which we had always thought was a really big species until we captured those "huge" sabrewings a day earlier.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center We had observed Magnificent Hummingbirds twice before--once on a field trip to southeastern Arizona and again during our 2009 solo trip to Guatemala, but those had been adult males with purple crowns and turquoise gorgets. This young Guatemalan male with a pollen-covered bill was a bit of an identification mystery that we had to consult the field guides to solve.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our next netted species wasn't a hummer, but it was every bit as colorful as the metallic-plumaged hummingbirds we had been handling. This intensely blue bird (above) was an adult male Red-legged Honeycreeper. In the hand, this bird was nothing short of breathtaking. His name correctly suggests he uses his long hummer-like bill in part to take nectar.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center The "red-legged" part of this bird's name is also perfectly apt, as shown in the photo just above. It's hard to imagine a more brilliant contrast that the red skin of a honeycreeper's legs against the deep, rich blue of his contour feathers.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's interesting that female Red-legged Honeycreepers (above) exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism with their dull neon green body plumage. Female legs are also somewhat paler than those in males.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along with honeycreepers, the hummingbirds kept on coming on 25 February, with an appropriately named Long-billed Starthroat (above and below) being the next species to be captured at Vesuvio. The bird in the photo is an immature male just starting to get its greenish-blue crown and purplish-red gorget--plumage that is similar but not quite identical in males and females; the latter have green crowns and mostly black gorgets. Its congener--the Plain-capped Starthroat that we have captured several times in Costa Rica--has a bronze-green crown and a metallic gorget that is more red.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Long-billed Starthroats have a vast distribution, from southern Mexico south to the entire Amazon Basin; the species also is reported from Trinidad. Both starthroats do indeed have very long mandibles, all the better to probe for nectar in the tubular flowers of various species of Erythrina trees.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of the birds we captured at Vesuvio, non-migratory hummers and honeycreepers did not have a lock on colorfulness--as shown in the breeding attire worn by an adult male Wilson's Warbler (above). First described in 1811 by Alexander Wilson, an early American ornithologist who preceded John James Audubon, the species breeds across Canada and into the western U.S. We've encountered it rarely at Hilton Pond Center, with only four individuals banded during 30 years of study; all came through South Carolina during autumn migration.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY SEVEN • The morning of 26 February we took our usual bumpy ride back up Atitlán Volcano to our Vesuvio banding station, ever-hopeful that today would be the day we would finally capture AND band a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Ernesto had been watching several ruby-throats foraging in a little settlement a couple of hundred yards from our original net lanes, so we moved some mist nets to that locale. Right away we caught . . . yet another NON-Ruby-throated Hummingbird! This time it was an apparent adult male Green-throated Mountain Gem (above), a species we had handled once before during hummingbird banding session we offered for young ornithologists in El Salvador. The taxonomy of the various mountain gems (Lampornis spp.) is poorly understood, but the Green-throated Mountain Gem (L. viridipallens) ought not be confused with the somewhat similar Green-breasted Mountain Gem (L. sybillae) that occurs only in eastern Honduras and northwestern Nicaragua.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our next hummingbird capture was yet another dark and iridescent species, this time an apparent subadult Green Violetear (above and below). The species is named for its ear patch, although the violet is not so obvious in younger birds and in the female; the latter has a narrower violet throat band than do adult males. Green Violetears breed from southcentral Mexico to Bolivia and northern Venezuela and are not known to migrate. Nontheless, this Neotropical species is notorious for vagrancy and has shown up in at least 18 states and even as far north as Canada!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Finally, at 7:24 a.m. on 26 February--our third field day at Los Tarrales--one of the new nets snared a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. We carefully transported her to the banding table and made darned sure she didn't wiggle loose until we adorned her right leg with a tiny aluminum band inscribed with a unique number: H81101. This bird exhibited molt progress that--based on what we observed in late January in Costa Rica--we would expect for the end of February in Guatemala: She was about halfway finished with bringing in the new wing and tail feathers she would need to begin her long migratory flight back to North America in a month or so. Our banding scribe dutifully recorded molt condition and measurements on the data sheet and then watched as we colored the hummer's lower throat with non-toxic marker, using black ink (above) reserved for Guatemala RTHU. (At Hilton Pond Center we color mark all our ruby-throats with green dye, using blue in Costa Rica and purple in Belize. Color marking allows us to observe banded birds after release and greatly increases the possibility of a re-sighting back north on the hummer's breeding grounds.) With that we offered the newly banded female RTHU a little sugar water and sent her on her way, satisfied that the GuateNaughts had just become our first citizen science group to capture AND band a ruby-throat in Guatemala. In honor of this auspicious accomplishment, we officially re-christened them the "GuateNeers," a name that also acknowledged earlier ground-breaking hummingbird work by our Costa Rica "Pioneers" in 2004 and the "Belize-Oneers" in 2010.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Relieved at finally capturing a Ruby-throated Hummingbird, the GuateNeers went right back to their stations and within a few minutes had netted a bird very different from a hummer. It was an LBJ--a "Little Brown Jobber"--and we knew just what it was because we had banded one not too long ago back in West Virginia. The GuateNeers had to pull out their field guides, however, and puzzled over the illustrations of sparrow-like Neotropical migrants; they were surprised when they realized they had just captured a Lincoln's Sparrow. The group was especially pleased when they consulted the official list of birds for Los Tarrales and found Lincoln's Sparrow had never been reported from the Reserve. Needless to say, it was pretty cool being able to add to a long list that already contained at least 331 bird species. Lincoln's Sparrows nest on the ground in boggy habitats across Canada, Alaska, and the northeastern and western U.S. and migrate only about as far south as El Salvador. We occasionally get them on Christmas Bird Counts in South Carolina and since 1982 have banded just six as migrants at Hilton Pond Center.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center At 9:10 a.m. one of the net tenders again yelled out "Bird!" and then changed the call to "Hummingbird!" Then, with even more emphasis, she cried "Ruby-throat!" and we knew we had our second target bird in Guatemala. This RTHU turned out to be an immature male (above) with moderate dark throat streaking and two tiny red gorget feathers. He, too, was about halfway through his wing and tail molt and needed to get on the stick about bringing in a full red gorget he would need sometime soon to attract the attention of females within his North American breeding grounds. And at 11:58 a.m.--just as we were getting ready to shut down our netting operation--we heard the "Hummingbird!" call once again. This time we'd caught another female ruby-throat, giving us a total of three Ruby-throated Hummingbirds for the day. Perhaps the 2011 jinx had been broken after all. Not!

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY EIGHT • With three ruby-throats banded, the GuateNeers felt pretty positive as we drove up the volcano on 27 February for what would be our final day of field work in Guatemala. Once at Vesuvio everyone took a final look at sunrise over a distant volcano and went right to work deploying mist nets and traps. The latter never did capture anything but the nets were working as desired. First bird caught was a warbler with a yellow belly and gray bib; we knew it had to be one of three species: Mourning, Connecticut, or the almost unpronounceable MacGillivray's Warbler. One look at the broken eye ring and we knew we had in-hand the first MacGillivray's Warbler we'd ever held (above)--likely an immature female. This species breeds west of the Rockies in the U.S. and Canada and almost never strays eastward. As a Neotropical migrant, however, we banded it in the hope it would show up again in North America.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly after we released the MacGillivray's another hummingbird hit the nets. This one was by far the darkest, least iridescent hummer species we'd ever seen. Turns out it was an immature male Blue-throated Hummingbird (above) whose dark gorget had not yet become blue. The white facial stripes and very black tail with white outer tips were the most useful field marks in identifying this bird.

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center At 9:50 a.m. we captured our fourth Ruby-throated Hummingbird for the Vesuvio banding site--a female that ended up being the last of her species to be banded by the GauteNeers. Just after than yet another hummer hit the nets--this time a subadult male White-eared Hummingbird (above). This bird's metallic gorget was two-tone, with rich blue feathers close to the bill and brilliant green ones below that. The red mandibles and very large white ear patch added to the diagnostic characters that helped confirm the species. This White-eared Hummingbird was the 11th hummer variety we'd captured at Vesuvio--an amazing accomplishment when one considers we were there for only four mornings AND that there are only 39 species of hummingbirds in all of Guatemala! (By comparison, we've captured just eight kinds of hummingbirds in 11 trips to Costa Rica--a country that hosts more than 50 hummer species.)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center As the clock neared noon on 27 February, the dedicated GuateNeers knew our time for banding hummingbirds and other Neotropical species at Vesuvio had come to an end, so with mixed feelings they took down the mist nets, removed them from poles we stored in the building at the field station, folded up the portable traps, posed for the traditional group photo (above), and said goodbye to some local boys who had taken quite an interest in our operation.

|

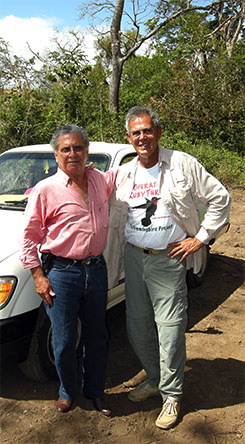

After that we headed back south for another excursion, this time with a new eight-person team that for the first time went to Guatemala. We traveled there because Alfredo Oliva Veliz, former owner of that now-lost Costa Rican aloe farm (at right with Bill Hilton Jr.), had another aloe finca a few miles southwest of Guastatoya in the Guatemala's Motagua River Valley. Alfredo had been most gracious in allowing us to conduct field research on his Costa Rica property and was quite pleased when we accepted his invitation to visit his stomping grounds. Little did we know last spring when we set up the expedition that our 2011 travails in Costa Rica would follow us across Central America to Guastatoya--hence this installment's reference to "fun and tribulations" in Guatemala. For an almost unbelievable but absolutely accurate account of what transpired in our first and latest and maybe last Guatemalan trip, please read on . . . .

After that we headed back south for another excursion, this time with a new eight-person team that for the first time went to Guatemala. We traveled there because Alfredo Oliva Veliz, former owner of that now-lost Costa Rican aloe farm (at right with Bill Hilton Jr.), had another aloe finca a few miles southwest of Guastatoya in the Guatemala's Motagua River Valley. Alfredo had been most gracious in allowing us to conduct field research on his Costa Rica property and was quite pleased when we accepted his invitation to visit his stomping grounds. Little did we know last spring when we set up the expedition that our 2011 travails in Costa Rica would follow us across Central America to Guastatoya--hence this installment's reference to "fun and tribulations" in Guatemala. For an almost unbelievable but absolutely accurate account of what transpired in our first and latest and maybe last Guatemalan trip, please read on . . . .

She spoke absolutely no English, but with Spanish-interpreting Ernesto around we were able to learn a great deal about local Guatemalan fare. Following the morning meal, the hummingbird crew bid Sandy adiós and boarded a sleek and shiny air conditioned bus for the steep traverse back down to Alfredo's Aloe Vera farm--the condition of which we had not yet described for our new participants. The team--eager to work after their previous day's flights, the bus ride over to Guastatoya, and what turned out to be a good night's rest--made note along the route of rugged terrain and mostly leafless vegetation (see photo above).

She spoke absolutely no English, but with Spanish-interpreting Ernesto around we were able to learn a great deal about local Guatemalan fare. Following the morning meal, the hummingbird crew bid Sandy adiós and boarded a sleek and shiny air conditioned bus for the steep traverse back down to Alfredo's Aloe Vera farm--the condition of which we had not yet described for our new participants. The team--eager to work after their previous day's flights, the bus ride over to Guastatoya, and what turned out to be a good night's rest--made note along the route of rugged terrain and mostly leafless vegetation (see photo above).

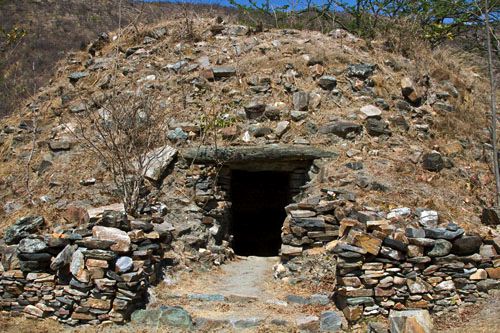

Situated in Guatemala's Eastern Highlands, Guaytán was a Mayan settlement occupied from about 200 BCE until as late as 900 AD. According to AuthenticMaya.com, Guaytán--which sits in part on a high hill--encompasses 142 mounds (dwellings or burials), three temples, two ball courts, five sculptured monuments, and 14 elaborate tombs with Mayan arches at their entrances (above). Guaytán was an important trading crossroads noted for its jadeite quarries and artisans who worked in jade (partially polished raw stone above right). Archaeologists have recovered many significant items at Guaytán, including stone and ceramic pottery, Pacific sea shells, green jade and black obsidian objects, and a Mayan codice.

Situated in Guatemala's Eastern Highlands, Guaytán was a Mayan settlement occupied from about 200 BCE until as late as 900 AD. According to AuthenticMaya.com, Guaytán--which sits in part on a high hill--encompasses 142 mounds (dwellings or burials), three temples, two ball courts, five sculptured monuments, and 14 elaborate tombs with Mayan arches at their entrances (above). Guaytán was an important trading crossroads noted for its jadeite quarries and artisans who worked in jade (partially polished raw stone above right). Archaeologists have recovered many significant items at Guaytán, including stone and ceramic pottery, Pacific sea shells, green jade and black obsidian objects, and a Mayan codice.

the crowd had dispersed and police had bulldozed the burning tires from the intersection, so we were free to drive through. And so it was that we arrived at Los Tarrales Reserve at dusk--ten and a half hours after we had departed Guastatoya on an expected five-hour trip.

the crowd had dispersed and police had bulldozed the burning tires from the intersection, so we were free to drive through. And so it was that we arrived at Los Tarrales Reserve at dusk--ten and a half hours after we had departed Guastatoya on an expected five-hour trip.

.

.