|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

NEOTROPICAL HUMMINGBIRDS 2013; PERSONAL PROLOGUE February 13, 2013 was a day of hectic preparation as I (Bill Hilton Jr.) tried to pull-together loose ends and compensate for time lost to a month-long series of strength-sapping viral illnesses--all while preparing to depart early the next morning for our first-ever Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expedition to Nicaragua. Sickness already forced me to cancel our annual research trip to Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica (scheduled for early February) but--if the doctor approved--I wasn't going to disappoint 12 people signed up as citizen scientist field assistants for Nicaragua. I breathed a labored sigh of relief when the nurse called on the afternoon of the 13th with news my respiratory infection and resultant pneumonia had "disappeared"; blood counts were normal, I wasn't contagious, and the physician thought it would be okay to depart Hilton Pond Center and fly south--with three caveats: 1) I was still pretty weak; 2) effects of pneumonia often take months to abate; and, 3) I would have to take it easy doing field work in the Central America. Thus, at 3:30 a.m. on Valentine's Day--which also happened to be our 42nd wedding anniversary--wife Susan dropped me curbside at the Charlotte airport, bid me fond farewell, and watched as I lumbered into the terminal with two oversized suitcases, a heavy day pack, and a wheeled camera bag stuffed with all the equipment and personal items I'd need for the next 35 days in the Neotropics. (Editorial note: The person who invented rolling luggage deserves a crown in heaven.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From Charlotte it was a quick hop to Miami for a two-hour layover--followed by the three-hour flight into Managua, whose Augusto César Sandino International Airport (above, from Google Earth) is a single 8,000-foot-long asphalt strip just south of Lake Managua. It's the fifth-busiest airport in Central America.

15 February 2013 Primary highways around Managua are reasonably flat, well-maintained, and with good traffic flow, but the last few miles to Montibelli climbed perhaps 2,000 feet over very bumpy dirt roads that slowed travel considerably. Montibelli ("beautiful mountain") is a series of old coffee plantations in the municipality of Ticuantepe ("Hill of the Fierce"); these fincas were established by Italian immigrants early in the 20th century on a chain of sloping-to-steep hillsides (above); the ridges--Las Sierras de Managua--are transected by small seasonal streams and have been farmed extensively for more than a hundred years. Although Montibelli is still in agricultural use, nearly 400 acres have been set aside as a sustainable tourism destination where native plants and animals are, for the most part, protected from human harm.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This region of Nicaragua is tropical dry forest somewhat reminiscent of our Operation RubyThroat study site in Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica, but more densely vegetated and lacking the vast savannas that support herds of cattle. We arrived during the peak of the dry season, so none of the local wet-weather tributaries had much water; partly as a result, butterflies (Banded Peacock, Anarta fatima, above) and more pestiferous insects like mosquitoes were few and far between.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The reserve boasts of more than 150 varieties of resident and migratory birds; 30-plus species of bats and terrestrial mammals; numerous frogs, toads, and reptiles (including a young Basilisk lizard, Basiliscus sp., above); plus a noisy dawn and dusk chorus provided by several troops of vocally competitive Golden Mantled Howler Monkeys. The complement of native trees, shrubs, vines, and herbaceous plants is equally diverse.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Montibelli includes a small lodge (Eco-albergue Oropendola) that became our home for the next ten days. Accommodations included several cabins such as the duplex in the photo above. Each room had a comfortable bed or two, a small fan, mosquito netting (which we did not need), a sink and flush toilet, and plenty of hot water for a shower. A spacious deck with rockers and a hammock was a nice amenity, especially because it enabled us to look out--or down--on big trees that shaded the entire area. There's nothing like watching birds from a hammock after a hard morning of field work! The Omega Crew quickly added a final touch by hanging sugar water feeders above the deck railings of several cabins, allowing a close view of hummingbirds and providing a spot for hummer traps.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Montibelli's open-air dining area served home-cooked meals that typically included meat (beef, chicken, or fish), vegetables (squash, greens, etc., with beans and rice frequently as a side dish), juice, and sometimes a salad. Since we were in the tropics we were surprised fresh fruits were seldom on the otherwise tasty and filling menu--even though adjoining farms grow white pineapple, lemons, passion fruit, plantain, bananas, and dragonfruit (known locally as pitahaya) that is produced by a night-blooming epiphytic cactus, Hylocereus costaricensis (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From their respective porches, members of the Omega Group had an excellent perspective of the surrounding forest, including the valley trail (see photo above). This well-traveled path wound up a shallow gorge toward an area of Montibelli where earlier researchers had run mist nets and banded resident and migratory birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After scouting the valley trails the Omega Group returned for an afternoon siesta and to watch feeders they had hung on the cabin decks that morning. Among other things they could watch the antics of long-tailed Squirrel Cuckoos (above) as they slurked about in treetop foliage.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center More important, however, we soon began to hear the familiar buzzing of hummingbird wings--a good sign there was at least one species of trochilid in the neighborhood. First to visit the porch feeders were Cinnamon Hummingbirds, but we were delighted shortly thereafter when a green-backed hummer with an unmarked throat and white spots on outer tail feathers zipped into view and stopped long enough to lap up a little sugar water. Yeehaw! It was a Ruby-throated Hummingbird! This first bird (above) was a female whose central rectrices were missing--an indication she had begun molting her tail feathers in preparation for the long migration back north a month or two hence. Needless to say, the presence of this RTHU was exciting and a bit of a relief since it was the species our Operation RubyThroat team was traveling a long way to study.

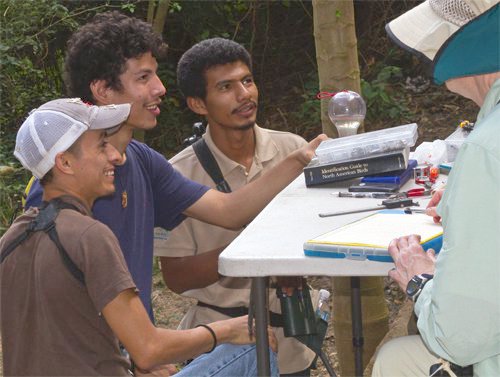

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Thanks to our request relayed by Holbrook Travel in-country representative Gilberto, several weeks earlier Montibelli's resident guides had hung a few hummingbird feeders at a likely site along the valley trail where we would be running mist nets after our citizen scientists arrived. These guides--Allan, Allejandro, and Juan (front to back, above)--assisted immensely by orienting us to local habitats, providing metal poles on which we deployed our mist nets, checking old banding data from earlier researchers, carrying gear, making everyone feel welcome, and generally helping out in any way asked. We're grateful for all they did.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 16 February 2013 On the morning of 16 February the Omega Group and Mizael headed for the airport in Managua to meet and greet 12 incoming members of the first-ever Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expedition to Nicaragua. Wise to the ways of customs and immigration (above), many in the group were old hands at this sort of thing; in fact, eight team members had been on at least one of our previous expeditions--and four had participated in FOUR! Returnees were Pat Barker (Charleston WV), veteran of Costa Rica-West 2010, Belize 2011, Guatemala 2011 & Costa Rica-East 2011; old pals Anne Beckwith (Durham NC) & Kathy Roggenkamp (Carrboro NC), veterans of Costa Rica-West 2008, Belize 2010, Guatemala 2011 & Costa Rica-East 2012; Ethelyn Bishop (Laurel MD), veteran of Costa Rica-East 2011 & Costa Rica-West 2012; spouses Mary Kimberly & Gavin MacDonald (Decatur GA), veterans of Costa Rica-West 2009, Belize 2010, Guatemala 2011 & Costa Rica-East; Elisabeth Curtis (Carrboro NC), veteran of Costa Rica-West 2007 & Belize 2010; and Nancy Meier (Catonsville MD), veteran of Costa Rica-East 2011. Our four newcomers were best buddies Nancy Cowal & Marcia Lyons (Buxton NC) and the husband-and-wife duo of Helen & Lee Peachey (Merion Station PA).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were especially thankful in Nicaragua to have those eight team members who already knew our modus operandi and who, for the most part, had worked together in the field at various study sites. In light of the trip leader's health difficulties, it was good to know the veterans would be able to take up the leader's slack as he continued to recover from effects of pneumonia. It was also great to see the four newbies fitting in almost instantaneously; by the time we had finished the 40-minute bus ride from airport to Montibelli they had already bonded and become integral members of the group.

Nicaragua was the fourth Central American country to which teams of citizen scientists had journeyed on behalf of Operation RubyThroat. That first expedition to Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica 'way back in December 2004 was appropriately named "The Pioneers," so all subsequent first-time groups at a new study site have honored those Pioneers with names that have the "-eer" suffix. Thus, the first team to Crooked Tree became the "BelizeOneers," the Guastatoya group was the "Guateneers," and the 12 folks who first worked in Chayote fields at Ujarrás in eastern Costa Rica were dubbed the "Chayoteers." With this theme in mind, it was pretty obvious our first-ever team at Montibelli just had to be the "Nicaneers"--an appropriate nickname because both male and female Nicaraguans refer to themselves as Nicas.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After checking into their rooms and unpacking, the Nicaneers got a brief walking tour of the area near the lodge and then spent the rest of the afternoon wandering about looking for birds. (Marcia Lyons & Nancy Cowal, above, especially enjoyed watching canopy birds from the deck outside their cabin.) Mary Kimberly once again volunteered to keep the team's Official List of Species Seen or Heard; our only rule is that to be counted a bird must be observed and identified by at least two members of the group. After supper we had our usual orientation meeting, an initial review of the history of Operation RubyThroat in the Neotropics, and a discussion of project goals and what the group would be doing the next day and thereafter in the field. 17 February 2013 Next morning (17 February) ever-dependable Ernesto made a woodpecker-like knock on the cabin door of each team member, awakening them all in time to get dressed and have a sip of coffee before heading out for the first day of field work. Unlike our previous expeditions to Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Belize, there was no need to board a bus to travel to the study site; at Montibelli it was merely a matter of walking a few hundred yards from the lodge. The team divided up the gear--including net poles; mist nets and traps packed into what we nicknamed the "Blue Suitcase Formerly Known as Green" (in honor of a battered and just-retired suitcase used on all 20 previous expeditions); a folding table and chairs; and the leader's personal items he was too weak to carry--and headed down the valley trail.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Nicaneers soon arrived at a spot called "The Wall," remains of a now-demolished building used during the Sandinista insurrection in the 1970s. It was at this site where our Nica guides had hung hummingbird feeders in anticipation of our arrival, and where mist netting had been conducted by previous researchers. The Wall provided a centralized shady spot where each morning we would unfold the banding table (above, with Ernesto processing a bird and Kathy Roggenkamp scribing while Nica guides look and learn), put up a trap baited with sugar water (below), and deploy the first of a dozen nets to be operated during the week.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our experienced Nicaneers worked rapidly that first morning, selecting and clearing net lanes and putting up the 42-foot-long mist nets designed to catch birds. The newbies caught on quickly and even before everything was in place we heard the call of "Bird!"--requiring that Ernesto jog to the net in question and carefully extract the new capture from the mesh. As might be expected when using non-selective capture methods such as mist nets we had no control over which birds might become entangled, so were were bound to catch more than just our Ruby-throated Hummingbird target species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In fact, that first capture turned out to be a Neotropical migrant even more colorful than a ruby-throat: An adult male Painted Bunting (above) in full breeding plumage--quite a bird to start our banding adventures in Nicaragua. Through our Master Bird Banding Permit we are authorized by the Bird Banding Laboratory in Laurel MD to apply U.S. bands to Painted Buntings we catch in Central America, but only because these Neotropical migrants eventually could be encountered someday back in North America. Such authorization includes warblers, thrushes, and other birds that travel far north of Nicaragua to breed; the permit does NOT allow us to band resident Central American species that don't occur north of the Rio Grande. Our newly captured male bunting received an aluminum band bearing a number in BBL format: A four-letter prefix inscribed over a five-digit individual number--in this case 2151-29901. We ended up with three male and two female Painted Buntings banded that first day, along with a second-year male Indigo Bunting.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our next capture was a resident non-migratory tropical species we have mist netted elsewhere in Central America--a female Barred Antshrike (above). It was nice to have this familiar species in-hand again--especially when we looked at her legs and saw that she already bore a band, but one with a very different inscription than those we brought from the U.S. The band read simply "NIC 122"--obviously a band of Nicaraguan issue. When we asked our Nica guides about this bird they told us there had been no banding at Montibelli in at least three years, so the band likely had been applied by local researchers in 2010, or before. Alas, although the Nicas had copies of some local banding data, they didn't have any info about our newly recaptured antshrike.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Things moved very quickly that first morning--so much so that we frequently called in team members for "show and tell." During these sessions we had them examine birds in the hand and work through the identification using field guides to Central American birds. This is sometimes a difficult task because resident avifauna are all new to our citizen scientists from up north and it often takes a while to figure out subtly different species such as the male Red-throated Ant Tanager above--which the Nicaneers claim looks an awful lot like a male Red-crowned Ant Tanager. The Omega Group is always careful not to blurt out the name of a new species, knowing team members learn and remember much more by figuring out the I.D. themselves.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At 8 a.m. we definitely had to call in the Nicaneers to see the latest capture. The first net we had erected had a tiny bird in it--a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird (above) that soon was to become the first of her kind ever banded in Nicaragua. Since this was our target species the group was elated and looked on intently as we measured and banded the hummer, finishing up the procedure by adorning her throat with temporary orange dye we used in Nicaragua to allow us to make observations of banded RTHU after release. The dye lasts only about six weeks and should disappear by the time this female migrated back to North America sometime between March and May. (NOTE: We use different colors of dye for ruby-throats at our various banding sites: Turquoise in Costa Rica, purple in Belize, black in Guatemala, and green at Hilton Pond Center in York SC.) It was quite satisfying to get a Ruby-throated Hummingbird on our first field day in Nicaragua! After we released the hummer half the team took a short walk back to the lodge for breakfast while the remaining six stayed to monitor mist nets. When the first bunch returned they brought breakfast to Ernesto and the bander as the other half of the team went to the lodge. This procedure worked well during the week and meant the kitchen staff didn't have to get up extra early to feed us before we went out to band birds. It also allowed us to make optimal use of the hours just after dawn--usually the best time to catch birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That first morning continued to be eventful. Among other things we captured three more female Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, plus two birds with Nicaraguan bands--NIC 155 and NIC 1028. Both were brightly colored Rufous-capped Warblers (above), a non-migratory species that is sexually monomorphic, with both sexes looking essentially alike.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On 17 February we also caught and banded a Neotropical species we doubt will ever appear at Hilton Pond in South Carolina. It was an adult male MacGillivray's Warbler (above)--a migratory parulid that breeds in the northwestern U.S. and western Canada. Its similar-looking congeners--Mourning Warbler and Connecticut Warbler--do occur in the east; MacGillivray's is usually distinguished from them by a broken white eye ring. Although our only other species banded on 17 February was a Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, all in all it was a great first day in the field. Bird activity did slow down considerably by late morning so at 11:15 a.m. we gave the order to furl the nets but leave them in place overnight--a luxury we'd never had at any of our other Neotropical study sites where pedestrian or vehicular traffic might have led to net damage or theft. Since Montibelli is private property with a history of ornithological research, we felt confident in simply rolling the nets tightly so nothing would get caught in our absence. After lunch the team had the afternoon free--a chance to wander the trails with camera and binoculars or to rest up a bit after the previous day's flights from up north.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the nicest things about the view from decks outside each room was the lush vegetation--particularly all the blooming Sacuanjoche trees, known technically as Plumeria alba. These showy white and yellow blossoms (above) are the national flower of Nicaragua (and oddly enough, of Laos, where the species is not native). The flowers are very fragrant at night when the odor attracts nocturnal Sphinx Moths as potential pollinators. Curiously, Plumeria flowers have no nectar, so the moths get no reward for their pollination efforts. After watching birds and blossoms all afternoon it was supper at 6 p.m., followed by the evening meeting from 7-8:15 p.m. Then it was off to bed for a sound night's sleep--and dreams of banding a total of four ruby-throats during our first field day in Nicaragua. 18 February 2013 We got off to a fast and early start on 18 February, mostly because the nets were already up and we merely had to unfurl them and--in a few cases--tighten up the guy wires. By 7 a.m. we had our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird, another female that brought our running total to two. We caught no more RTHU that morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also in the nets early were another female Painted Bunting and our first two Ovenbirds (above) for Nicaragua. (One of these ovenbirds was recaptured two more times during the course of the week.) Despite their thrush-like appearance, Ovenbirds are warblers. They breed in the northeastern and north central U.S. and into central Canada and take their name from the habit of building a nest with a "roof"--a structure reminiscent of old-time outdoor clay ovens.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Of significant interest to our Nica guides were three other resident birds that ended up in our mist nets--all of which bore Nicaraguan bands. One was a male Dusky Antbird (above), a sparrow-sized gray bird whose most significant field mark is a tuft of white shoulder feathers that usually aren't visible. A close-up of the antbird's leg shows a band (NIC 1056) that is dull rather than shiny and somewhat worn--a good sign it had been on the bird for at least a few years. (Remember, there apparently had been no banding activity at Montibelli since about 2010.) The other two recaptures were a Gray-headed Tanager (NIC 815) and a Rufous-and-white Wren (no prefix 481).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Back at Hilton Pond in the Carolina Piedmont, there's only one member of the Pigeon Family (Columbidae) we're likely to see and it's the Mourning Dove. In Central America, however, there seem to be all sorts of doves that vary in size from the diminutive Common Ground Dove to big lunkers like the Scaled Pigeon. One of the larger, heavier bodied columbids that weighed down a mist net on 18 February was a White-tipped Dove (above). This species takes its name from prominent white tips on its outer tail feathers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When we capture any sort of dove we always take a close look at its legs and plumage, and we especially attend to its eyes. Bird eyes are fascinating structures with much greater acuity than those of humans, but what we find of particular interest is the appearance of a dove's iris and color of its eyelids. In the case of the White-tipped Dove above, the large pupil appears black, with an highly granular iris that's yellow rimmed with red. There's no white in the dove's eyeball--just an orb of deep black. To top it off, the eyelids are naked with blue skin--an avian form of mascara that undoubtedly is some sort of signal to other White-tipped Doves.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Nicaneers were equally fascinated by the dove's eyes, but that bird got upstaged a few minutes later when the national emblem of Nicaragua flipped into one of our nets. It was a Turquoise-browed Motmot (above), a species we had seen perched in trees along the trail at Montibelli--swinging its long unusually shaped tail back and forth in pendular fashion. Motmots, in the same order (Coraciiformes) as the kingfishers, are cavity nesters that use their strong serrated bills (see photo) to catch lizards and big insects and to excavate burrows in cliffs and stream banks. Although conventional wisdom is that motmots intentionally preen their long central feathers to create the distinctive paddle shape, this is not the case; barbs on these feathers are not well-formed and break off due to abrasion and normal preening activity. Ernesto remarked that Turquoise-browed Motmots in Nicaragua seemed to have heavier brows than their conspecifics in Costa Rica.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We'd be remiss if we didn't mention an interesting phenomenon most of the Nicaneers experienced while scribing data at the banding table. Every now and again we'd be distracted by what looked like a crystalline butterfly flitting through the sunlight but always turned out to be a transparent winged seed (above) dancing down from the canopy. Initially we were confused about the source of these unusual seeds but finally concluded they came from six-inch ball-shaped fruits on vines that twined their way into the tallest trees. We believe we're correct in identifying these as the imported Javan Cucumber (AKA Malay Climbing Gourds), Alsomitra macrocarpa.

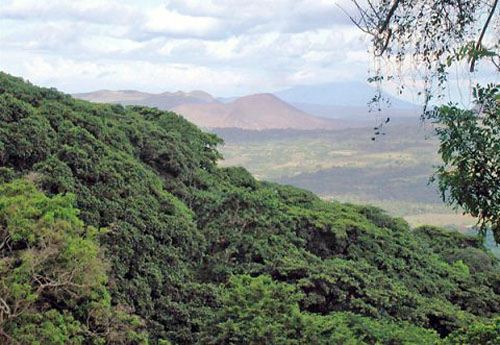

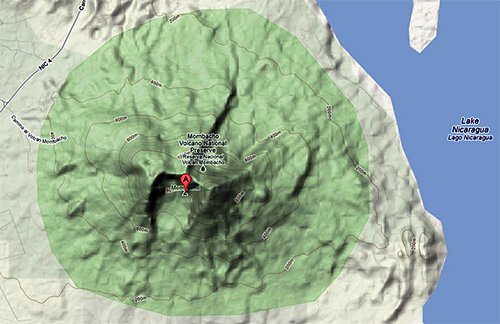

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a successful morning of banding the group closed the nets, went to lunch, and took a short break before boarding a sleek and shiny minibus for our first off-grounds excursion to one of several volcanoes that dominate the landscape of southwestern Nicaragua. The day's destination was Mombacho, a "stratovolcano" (AKA "composite volcano") that was formed by successive build-up of many layers of lava, pumice, and ash. Steep-sided Mombacho arises abruptly from the western shores of Lake Nicaragua near Granada. The Google Maps topographic map (above) gives a feel for just how abrupt the elevation change really is--from 300-foot elevation at lake level to 4,409 feet at the apex.

Mombacho (above) is an active volcano that last erupted in 1570 AD but still releases hot water vapors and gases. On many days--including the one when we visited--the top is shrouded in fog. This creates a cloud forest--one of very few on the Pacific slope of Central America (most are on the Caribbean). The cloud forest engulfs all four of Mombacho's craters and includes lush vegetation such as epiphytic orchids, bromeliads, lichens, and mosses. This super-rich ecosystem is home to at least 60 mammalian species, 174 kinds of birds (perhaps a third of which are Neotropical migrants), 30 varieties of reptiles, ten amphibians, and 750-plus plant species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The cobblestone road up Mombacho is so steep in places (above) that most bus drivers transfer passengers to special trucks with low gear ratios. Private vehicles with four-wheel drive and adventuresome drivers sometimes attempt the trip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One advantage of taking a Mombacho truck is that it's open-air, which gives unimpeded views of birds and vegetation along the way. Several groups of White-throated Magpie Jays entertained us as the truck chugged to the incline. Halfway up the mountain we stopped at the home of Café Las Flores, a well-known Nicaraguan coffee that apparently thrives in the higher humidity and cooler temperatures of Mombacho's middle elevations.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a quick stop to sample the coffee we re-boarded the truck and headed back up the mountain to the top, where a local guide met us for a 2.5-hour walking field trip around one of Mombacho's craters. Again, because the day was overcast and we were in the cloud forest there were no scenic vistas, but the group had plenty of good looks at local birds and even a gray-haired Two-toed Sloth (above) huddled up and sleeping on an overhanging branch--with two of its massive claws barely visible. While waiting for the truck to take the group down the mountain, a young man emerged from the visitor center and extended his hand to trip leader Hilton, 19 February 2013 On 19 February the Nicaneers had nets open and running by 6 a.m.; by this third day of field work they were getting quite efficient. An second-year male Painted Bunting at 6:40 a.m. was the first catch of the day, after which things slowed down considerably, with a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird at 8:20 a.m. bringing our running total for her species to six. An Ovenbird followed at 10:12 a.m. as one of just three Neotropical migrants banded that morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite our lack of banding productivity, we kept catching resident birds that already carried Nicaraguan bands. One was a male Barred Antshrike (above) with striking black and white plumage and big yellow eye; his number was NIC 893. We also caught a third banded Rufous-capped Warbler (NIC 30), and then netted three birds of special interest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first was another adult male Painted Bunting (above). Although we had already captured and applied bands to several PABU, this bird already had a band--and it didn't have a NIC prefix. No, it was a band issued by the Bird Banding Lab (BBL) back in the U.S. and the number was 2321-32693. The Nicaneers were quite excited by this bird because a U.S. band meant either it had been banded at Montibelli by earlier researchers and returned to this wintering site OR that it had been banded in the U.S. and had flown south to Nicaragua. Since the BBL now has an on-line Web form for reporting banded birds one might encounter, we whipped out our trusty iPhone and decided to use some precious international roaming minutes to see if we could connect via the Nicaraguan cell phone provider to learn more about the bunting. Sure enough, the Web form came up--pretty phenomenal when you consider we were in the middle of the dry tropical forest at Montibelli in a Central America country--and we began the tedious task of keying in our recapture data on the tiny on-line form.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eventually we were able to input all the pertinent information--band number, bird species, location and date of recapture, and our contact info--so we just had to wait for the BBL computer to do a search of its massive database. The download seemed to take forever but eventually we got the following on-line response: 1) There is a discrepancy or potential error in your report that will place it in a hold file until time allows us to work on resolving it; or, 2) The bander has not yet submitted the data for this band so we are unable to process your report at this time. With the bird in-hand and its band examined closely by several Nicaneers we knew our report was not in error, so that left the disappointing possibility that whoever had banded this Painted Bunting had not yet submitted his/her data to the Bird Banding Lab. If the bird was originally caught at Montibelli and there had been no banding there for at least 2-3 years, that meant the bander was 'way behind on the required task of submitting records to the BBL in timely fashion. Likewise, if the bunting had been banded on North American breeding grounds in a preceding season, the bander had some catch-up paperwork to do. [NOTE: After a tedious inquiry by the Bird Banding Laboratory we finally learned in February 2018 that the Painted Bunting in question had been banded 27 March 2011 at Montibelli as an after-2nd-year male by another researcher who had finally submitted his data. At time of our recapture in 2013 the bird would have been classified as after-4th-year.]

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The next bird of interest also bore a U.S. band (2321-32638) that was close to the number of the Painted Bunting just described, but this individual was perplexing in a different way. It was obviously a Lesser Greenlet, a Central American species that does NOT migrate and that should not have carried a U.S. band from the Bird Banding Laboratory. The group pondered the possibilities on this banding anomaly and finally concluded by consulting field guides (above) that the bander must have confused the greenlet with some Neotropical migrant--most likely a Tennessee Warbler in breeding plumage. In any case, when we submitted the band number via the BBL's Web form, we AGAIN got the same dreaded response: Either we had made an error--we didn't--or the bander had not yet submitted the required data. Here was another Nicaraguan banding mystery that remains to be solved. [NOTE: At the same time we found out about the history of the banded Painted Bunting described above, we learned the same researcher finally agreed he must have improperly identified the Lesser Greenlet in 2011 as a Tennessee Warbler. As non-migratory Neotropical residents, Lesser Greenlets should not be banded with U.S. bands issued by the Bird Banding Laboratory.]

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The morning's third mist-netted bird that bore a band (NIC 766) was one that had the Nicaneers all a-twitter: An adult male Long-tailed Manakin (above) with jet-black body, brilliant scarlet crown, and sky-blue back--to say nothing of those amazingly long, slender tail feathers that must play a significant role in attracting attention of prospective mates. Manakins exhibit complex breeding behavior in which several males gather together to form a "lek" in which they call and dance. This assemblage apparently attracts more females than a solitary male can bring in on his own. Like most birds, manakins look much smaller in-hand than they do in a natural setting; the male above was smaller than your average sparrow. With another intriguing morning of banding--and recapturing--under their belts, the Nicaneers had the afternoon free to explore the hills and valleys of Montibelli and to add to the ever-growing list of birds seen or heard. Some folks also took well-deserved siestas before coming to supper and the usual evening conclave at which team members told us a little more about their backgrounds and their lives back home. 20 February 2013 Despite an early start, 20 February turned out to be even slower banding-wise than the day preceding. Only one Ruby-throated Hummingbird--yet another female--mist netted at 7:38 a.m. brought our running total at Montibelli to seven, which was a surprisingly low number after four days in the field. As the morning progressed we captured and banded four more of those seemingly ubiquitous Ovenbirds but caught no local birds bearing Nicaraguan bands.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We did manage to net a few unbanded resident species, however, including a female Long-tailed Manakin (above) that looked very different from the male we caught one day earlier. Female manakins are far less colorful than their mates, suggesting their drab olive green plumage serves not to attract attention but to defer it as they sit on a nest incubating for long periods of time. The female does have central tail feathers longer than the others, but not nearly the length of those on the male.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps more common than Ruby-throated Hummingbirds at Montibelli were Cinnamon Hummingbirds (above) a non-migratory species we have encountered on our expeditions elsewhere in Central America. The species occurs most commonly in tropical dry forests and shrub land on the Pacific slope. This sexually monomorphic hummer is distinguished by a bronzy-green dorsum and buffy coloration on its throat, breast, and belly. Tail feathers are rusty at the base, which sometimes leads observers to confuse the species with the even more-common Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, but the latter has an iridescent green throat and breast. Both species also have red bills with black tips; the amount and intensity of red appears to increase as younger birds age.

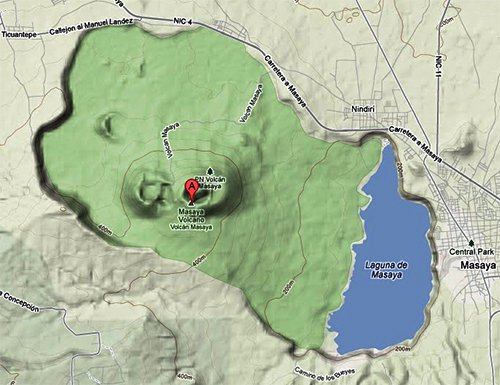

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a slow morning in the field and a tasty lunch, the Nicaneers again boarded our tour bus for a short road trip to Masaya Volcano, formed by on-going flows of liquid lava. Because such mountains are big, wide, and relatively flat they are called "shield volcanoes"--very different from steep-sided stratovolcanoes like Mombacho that we visited earlier in the week. As shown by the Google Maps topo map above, Masaya includes two volcanoes and a total of five craters. Its "shield" ranges in elevation from 985 to 2,066 feet, with a large freshwater lagoon on the eastern perimeter between it and the town of Masaya.

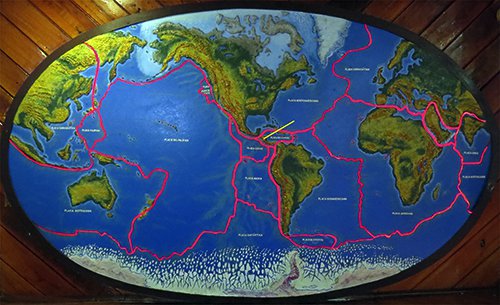

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the image above--taken from Mombacho--Masaya is in the middle of the photo; its flattened, shield-like shape is visible, as is the plume of sulfur dioxide gas and water vapor constantly yields. Relatively recent major lava flows occurred in 1670 and 1772, with major explosive events in 1999, 2001, and 2003. Needless to say, all this qualifies Masaya as an active volcano--one that supports only sparse vegetation over most of its breadth. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Masaya boasts of a large and attractive visitor center--the best we've seen in a national park in Central America--complete with artwork, dioramas, and expansive observation decks. One 20-foot-wide exhibit (above) nicely portrays the various geological plates of the world--locations where there is exceptional volcanic and earthquake activity. You'll note that Nicaragua (yellow line) is quite close to the intersection of two very dynamic plates. (NOTE: Click on the photo above to open a larger version in a new browser window.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After getting oriented at the visitor center we took the bus to the very edge of the largest crater (above), where a rotten egg smell reminded us Masaya was producing large amounts of sulfur dioxide. The steam and smoke was so dense we were unable to see the crater bottom several hundred feet below. We birded the area for a while and the descended for a short trip to the little town of Catarina a few miles to the southeast.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Catarina is a small (population 4,500) tourist-oriented town with lots of eateries, galleries, and small shops. At one (above) we haggled with a Mayan woman over purchase of an embroidered purse and matching sun dress for McKinley Ballard Hilton, our one and only granddaughter. (We got a great deal.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The main street of Catarina dead-ends at a large outdoor hillside amphitheater that looks out over Apoyo Lagoon (above), another scenic freshwater impoundment. (Much-larger Lake Nicaragua is in the far background, with the town of Granada not visible but just over the ridge.) Musicians playing everything from portable marimbas to guitars and trumpets serenaded passersby while street vendors sold traditional pastries, candies, and ice cream. After a pleasant interlude at Catarina it was back to Montibelli and the evening meeting.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 21 February 2013 On our fifth field day (21 February) we adopted an expanded strategy. Not only did we deploy our usual complement of mist nets, Other bandings on the 21st included two Ovenbirds, an adult male Painted Bunting, and three Indigo buntings (one adult male and two females). We also recaptured three birds with old bands on their legs: Two with Nicaraguan bands--another male Barred Antshrike (NIC 732) and a Plain Wren (no prefix 488)--and yet another Neotropical migrant with a U.S. band (2510-63862), in this case a Black-and-white Warbler with a pale face indicating she was a female. We dutifully went on-line with our iPhone Web application and attempted to determine the banding date and location for the BAWW, only to get the same response that the data had not yet been submitted by the bander. We suspect the three birds with U.S. bands were all captured originally at Montibelli, but we'll have to wait for further word from the banding lab to be sure.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With six ruby-throats banded that morning the Nicaneers were feeling pretty flush, so we shut down the nets and traps by noon, had lunch, and boarded the bus for a longer ride than usual. We were about to do something a little different than we'd done on any of our 18 previous Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Central America: Go to an entirely different location for an overnight field trip. Our destination was Ometepe, the towering two-volcano island in the middle of Lake Nicaragua--the largest lake in Central America and 19th largest in the world. To get to Ometepe we first drove more than two hours to San Jorge to catch a one-hour afternoon ferry. At the port we left the bus behind and boarded a three-decker boat named for Che Guevara (above), the Argentine Marxist revolutionary still revered by many Latin Americans.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center While we waited for the crew to load cargo--we watched with some amusement as several men wrested with and punctured a 55-gallon drum full of sticky molasses--we also go to do a little birding. On the jetty next to the dock were quite a few Snowy Egrets (above) with distinctive yellow feet at the end of long black legs. the individual in the photo had a splendid set of mating plumes--aigrettes that give such tall wading birds their common name. (NOTE: It's showy feathers like these that threatened herons and egrets worldwide in the 1890s as hunters shot birds for the feather trade. Fortunately groups such as the National Audubon Society--whose emblem is a Great Egret--stepped in and helped bring an end to the popularity of adorning ladies hats with feathers from dead birds.) When the crew of the good ship Che Guevara completed their sundry tasks, we said goodbye to the egrets and cast off in an easterly direction toward the distant peaks of Ometepe.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The boat ride out was a bit uncomfortable for some because the day was windy and the water was quite choppy, causing our craft to lurch more than we might have liked. This also made binocular use and camera work a bit difficult, so most of the group settled in on the bench seats (above) to talk about the events of the day, watching across the bow as we drew slowly closer to Ometepe.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As shown on the Google Maps image above, hourglass-shaped Ometepe likely would be TWO islands if Lake Nicaragua were just a little deeper. Its massive volcanoes--mile-high Concepción (5,2822') and Maderas (4,573')--are connected by a narrow, low-altitude isthmus only a few dozen feet higher than surrounding water. The island is 19 miles wide east-to-west and about six miles wide at its broadest point. A well-maintained road circles the base of each of the two volcanoes, providing access for Ometepe's 42,000 residents. The vast majority of locals are Nicaraguan citizens, with very few expatriates from other countries.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When approaching Ometepe it looks like both volcanoes are active, but only Concepción emanates steam and gas; the clouds above Maderas are atmospheric, not volcanic. Concepción's most recent major eruption was in 1880, although minor events since then and as recently 2010 have resulted in non-mandatory evacuation orders. Maderas is extinct, with a small crater lake at its peak. The entire island of Ometepe is covered by nutrient-rich volcanic ash, making it a fertile place to grow plantains that are the island's primary export. Much of Ometepe is too steep to farm.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we approached Ometepe we could see its perfect conical shape (above) and that some of its slope was covered by ash landslides and old lava flow. Also visible was the lush vegetation of the lowlands. When our ferry docked in late afternoon we were met by local guide Aristides Flores Vanegas and his 15-passenger van that was our transport to our hotel, where we had supper and settled in for the night.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 22 February 2012 Next morning on Ometepe the Nicaneers were up bright and early, although several elected not to take showers because only cold water was available in some rooms. During breakfast at the hotel we had to deal with a small but brazen flock of White-throated Magpie Jays (above) that swooped onto tables and competed with us for food. We enjoyed the antics of these big corvids, but much to our chagrin the waiters were armed with slingshots and tried to shoot them. Fortunately, we witnessed no casualties.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our guide had arranged a whirlwind tour of Ometepe that included stops at a local finca where indigenous people had carved intricate petroglyphs (above) into surrounding rocks. Ometepe's oldest petroglyphs are pre-Columbian and date to about 1,000 B.C. The carvings often include spirals and circles, and there's even a somewhat newer rock calendar indicating the makers recognized a year about 360 days long. Turtles are a common theme for petrogylphs, as are other zoomorphic and anthropomorphic subjects.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center During our Ometepe tour we observed plenty of vegetation far too diverse to describe here. Among other things we saw Cacao trees, Theobroma cacao, with elongated fruits (above) that contain the seeds and mucilage from which chocolate is made.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One stop on the tour was at a large freshwater pool where tourists could refresh themselves. Most of the Nicaneers went swimming and also had opportunities to observe local wildlife, including a colony of camouflaged Proboscis Bats, Rhynchonycteris naso (above), roosting high up on a shady tree trunk. These bats often sleep lined up in a long row that some observers claim makes the group look like a big arboreal snake--something likely to deter potential predators.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From the swimming hole it was off to Charco Verde, part of the Ometepe Biosphere Reserve, where we observed Nicaraguan Sliders, Trachemys emolli (above). Several were sunning on exposed logs. Big females of this species can lay up to 35 eggs--which helps explain how this is the most common turtle on Ometepe (and elsewhere in Nicaragua).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In a tree not far from the slider we got our best look so far of a Golden Mantled Howler Monkey, Alouatta palliata, obviously a male. Various subspecies of this New World primate occur from Mexico to northwestern South America. Howlers are folivores that eat prodigious quantities of green leaves--something very difficult to process. This requires the monkeys to spend a great deal of time just resting and digesting, so rather than defending territories by energy-demanding physical confrontations they use distinctive vocalizations--their deep, resonant howls--to ward off trespassers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As our walking tour of Ometepe neared its end, we were pleased to see Prickly Pear cactus (Opuntia sp.) growing in well-drained soil along the trail. The succulent apparently had been flowering for a few weeks, with four unripe fruits forming on the pad next to one current yellow blossom. These seed-filled fruits eventually turn a reddish-purple and are relished by all sorts of wildlife from small mammals to terrestrial turtles. One can even find de-spined prickly pears at neighborhood grocery stores back in the U.S.; they can be eaten raw and make a tasty jelly. At the dock we bid farewell to our local guide and boarded the ferry for the return trip to the mainland. En route we had interesting conversations with several passengers, When the ferry put in at the dock we were met again by bus and driver, who took us back to Montibelli for a late supper and fond memories of Ometepe.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 23 February 2013 The Nicaneers approached their sixth and final day in the field with mixed feelings. They were tired and looking forward to getting back home but they also were very much enjoying their time in Nicaragua. With one final chance to capture birds for banding they unfurled their nets and had a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird in hand by 6:30 a.m. Once more we dispatched two people to run traps at the lodge and this paid off with an immature male RTHU caught at 10:30 a.m. These were our final two ruby-throats, bringing our six-day total to 15. We hadn't caught a ton of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds at Montibelli but could take satisfaction that these were the first ones ever banded in Nicaragua. Other birds banded during the final morning were all quite familiar to the crew: Three adult male Painted Buntings, a female Indigo Bunting (above), a second-year male MacGillivray's Warbler, and one more Ovenbird. With all these birds processed, it was time to close and take down the nets and place them in bags for transport, and to collect the ten-foot-long metal net poles to be stored at Montibelli.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For lunch we headed into the capital city of Managua for a stop at the open-air Restaurant Bucanero. There we we treated to great food and a serenade from a mariachi band (above) that at times sounded a lot like Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The view from the dining porch of the restaurant was especially pleasant, as shown by the photo above. Masaya Volcano is at upper left and Masaya Lagoon at center, while a Black Vulture wheels out of the picture on the right. Bright days and blue skies like this are standard during Nicaragua's dry season.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We took our time at lunch in Grenada because we were in no big hurry to get to our next stop--not because we didn't want to go but because the reason for going required we arrive there late afternoon. Our ultimate destination was Chocoyero-El Brujo Natural Reserve, one of Nicaragua's 78 public or private protected areas. Even if you don't know a lot of Spanish you can probably interpret an entry sign (above) at the visitor center: "Welcome. Chocoyero-El Brujo Wildlife Refuge in Ticuantepe. Nature, bird observation, hiking, and fun." The real draw at Cocoyero, however, are the chocoyos--big flocks of bright green Pacific Parakeets that nest communally in cavities in a huge rock wall within the refuge. They depart at dawn for distant feeding areas and return shortly after 4 p.m. each day in such numbers their raucous vocalizations drown out all other noise.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We got to the visitor center at about 3 p.m. and after a short presentation by a park guide started down the trail with him. Although our Nica guide spoke no English, Ernesto translated for him as he pointed out interesting local flora. At one point along the path we snapped an abstract photo (above) of termite colony's rough and longitudinal mud tunnel juxtaposed against the eye-like limb scar of an otherwise smooth tree trunk. A little further along we had to watch our step when a fast-moving colony of Army Ants marched across the trail. Since these voracious little insects were on their way to a foraging area it was best not to get in their way, lest we suffer more painful stings than we might like.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center About 40 minutes from the starting point we heard the sound of rushing water and suddenly came to a clearing where a tall, thin ribbon of water cascaded down the cliff we were looking for. This waterfall--fed by rainfall from higher elevations--is important for nearby residents; the city of Managua receives 20% of its drinking water from the cataract (up to 20 million gallons per day).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The waterfall was quite scenic but our real goal was to see those flocks of parakeets as they came in to roost. Sure enough, at about 4:15 p.m. we began to hear fluttering and whooshing of wings and then chittering and chattering as the 'keets arrived right on schedule. It was quite a spectacle seeing several hundred Pacific Parakeets swooping in, perching, and taking off again as they jockeyed for positions in nearby trees and on the cliff itself. These highly social birds clung to the cliff, sometimes nibbled on the mineral-rich rock, went in and out of holes, and even preened each others' feathers before settling down for the night. After watching this enchanting behavior the Nicaneers were satisfied to trek back out of the canyon for the bus ride back to Montibelli.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our final supper at the lodge was a feast of meats and vegetables, followed by desert and an evening meeting at which we summarized the results of our six days of field work in Nicaragua (see tables below). We thought that would be it for the evening, but the Montibelli staff had a little surprise in order: They had asked local dance teacher Heriberto Ortiz to bring his Xochipilt Dance Group for a Farewell Fiesta in which performers of all ages (see youngest ones above) demonstrated traditional Nicaraguan dance numbers. It was a touching gesture and we all appreciated the entertainment--and the talent. When the party broke up, the Nicaneers spent quite a bit of time talking and hugging, knowing they would be going their separate ways on the morrow.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 24 February 2013 Several Nicaneers had very early flights out of Managua on 24 February, so they they had to load their gear into the minibus and go off to the airport shortly before dawn. Nonetheless, everybody got up to see them off, and we were happy we had remembered to assemble everybody the preceding afternoon for our traditional group photograph (above). Later that morning the remaining team members made their way to the terminal and said goodbye to the Omega Group. Most of the Nicaneers boarded flights for home, but Bill and Ernesto had more field work to do--this time at Crooked Tree in Belize. We'll talk about those Operation RubyThroat expeditions--with two different groups--in our next installation of "This Week at Hilton Pond." In closing we offer our deepest appreciation to the Nicaneers who underwrote our 2013 Operation RubyThroat expedition to Nicaragua and helped us capture the first Ruby-throated Hummingbirds ever banded in that country. Without the assistance of these 12 dedicated citizen scientists the trip would not have occurred, nor would it have been so successful. We're especially grateful for their kindness and understanding as the trip leader dealt with the aftereffects of pneumonia in a location far from home. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center NICARAGUA BIRD BANDING SUMMARY On 17-21 & 23 February 2013 we spent six five-hour mornings running mist nets and/or live traps at Montibelli Private Natural Reserve near Ticuantepe in southwestern Nicaragua. Operation RubyThroat's citizen scientists ("Nicaneers") captured and banded 15 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris. To our knowledge this species has not been banded previously in Nicaragua. Included in the captures were three second-year males with incomplete red gorgets and 12 females of indeterminate age. (The photo above is of a female RTHU color marked with temporary orange dye; two bars indicate she was one of three birds trapped at the lodge at Montibelli; the rest were mist netted in surrounding dry tropical forest and received one orange bar.) Although Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were our target species, we incidentally mist netted 30 other Neotropical migrants. To the latter we applied bands from the U.S. Bird Banding Laboratory. Non-hummingbirds banded included:

We also mist netted numerous resident Nicaraguan birds. We examined and photographed these non-migrants but did not apply U.S. bands. However, several individuals bore Nicaraguan bands used by earlier researchers, undoubtedly at Montibelli. These included the following 11 birds:

We mist netted three birds with U.S. bands applied by other researchers. Two of these were Neotropical migrant warblers that breed in North America; the third was a non-migrant species (Lesser Greenlet) that likely was misidentified and that should have received a Nicaraguan resident band instead of one intended for migrants. We dutifully reported all three birds via the U.S. Bird Banding Lab's on-line Web form but learned the BBL has no record of these three bands having been used. The original bander apparently has not yet submitted banding data, so we await updated information on:

The Nicaneers observed (saw or heard) 99 species of birds during their nine days in Nicaragua, including birds spotted at Montibelli and during off-site field trips to Mombacho, Masaya, Ometepe, Chocoyero, and other locales. Numerous other vertebrate and invetebrate animal species were also observed and photographed, as were many kinds of native tropical flora. We look forward to mounting a follow-up Operation RubyThroat expedition to Nicaragua in February 2014, returning to Montibelli and perhaps also doing some hummingbird banding in the coffee plantations on Mombacho volcano. Operation RubyThroat: the Hummingbird Project is a research, education, and conservation initiative of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History in York, South Carolina USA. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All contributions are tax-deductible on your

NOTE: Info about next year's citizen science expedition to Nicaragua will be posted within a few weeks. In the meantime, you might consider joining us for our next Operation RubyThroat adventures in November 2013 at Lake Atitlán (southwestern Guatemala) or Ujarrás (Costa Rica's Caribbean slope). Details are at 2013 Tropical Trip Announcements. Summary reports for past trips are linked from the table below.

|

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

Click on image at right for live Web cam of Hilton Pond,

plus daily weather summary

Transmission of weather data from Hilton Pond Center via WeatherSnoop for Mac.

|

--SEARCH OUR SITE-- For a free on-line subscription to "This Week at Hilton Pond," send us an |

|

Thanks to the following fine folks for recent gifts in support of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History and/or Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project. Your tax-deductible contributions allow us to continue writing, photographing, and sharing "This Week at Hilton Pond" with students, teachers, and the general public. Please see Support or scroll below if you'd like to make an end-of-year tax-deductible gift of your own.

|

If you enjoy "This Week at Hilton Pond," please help support Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History. It's painless, and YOU can make a difference! (Just CLICK on a logo below or send a check if you like; see Support for address.) |

|

Make credit card donations on-line via Network for Good: |

|

Use your PayPal account to make direct donations: |

|

If you like shopping on-line please become a member of iGive, through which 1,200+ on-line stores from Amazon to Lands' End and even iTunes donate a percentage of your purchase price to support Hilton Pond Center.  Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. Every new member who registers with iGive and makes a purchase through them earns an ADDITIONAL $5 for the Center. You can even do Web searches through iGive and earn a penny per search--sometimes TWO--for the cause! Please enroll by going to the iGive Web site. It's a painless, important way for YOU to support our on-going work in conservation, education, and research. Add the iGive Toolbar to your browser and register Operation RubyThroat as your preferred charity to make it even easier to help Hilton Pond Center when you shop. |

|

BIRDS BANDED THIS WEEK at HILTON POND CENTER 13-24 February 2013 |

|

|

SPECIES BANDED THIS WEEK: * = New species for 2013 WEEKLY BANDING TOTAL: 4 species 20 individuals 2013 BANDING TOTAL: 32-YEAR BANDING GRAND TOTAL: (since 28 June 1982, during which time 171 species have been observed on or over the property) 126 species (32-yr avg = 65.2) 58,324 individuals (32-yr avg = 1,822.8) NOTABLE RECAPTURES THIS WEEK: Northern Cardinal (1) Purple Finch (1) House Finch (1)

All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center

|

OTHER NATURE NOTES: --The Center's Yearly Yard List 2013 of birds seen on or over the property stands at 32 species as of 13 Feb. --Last week's photo essay was about "Mid-winter Miscellany." It's archived and always available on the Hilton Pond Center Web site as Installment #563. All text & photos © Hilton Pond Center |

Upon clearing customs I was met by my long-time Costa Rican guide and Operation RubyThroat Neotropical collaborator Ernesto Carman Jr. and by new friend

Upon clearing customs I was met by my long-time Costa Rican guide and Operation RubyThroat Neotropical collaborator Ernesto Carman Jr. and by new friend

speaking English with a heavy accent. "Hello, Beal. It's me, Roger. Do you remember me?" It was

speaking English with a heavy accent. "Hello, Beal. It's me, Roger. Do you remember me?" It was

we also sent two Nicaneers to sit on porches back at the lodge while watching portable Dawkins traps we'd hung there and baited with sugar water

we also sent two Nicaneers to sit on porches back at the lodge while watching portable Dawkins traps we'd hung there and baited with sugar water

all of whom were quite curious about our Operation RubyThroat hummingbird research in Central America. One woman noticed the Nicaneers' binoculars and asked about our work; we were pleased to learn she was

all of whom were quite curious about our Operation RubyThroat hummingbird research in Central America. One woman noticed the Nicaneers' binoculars and asked about our work; we were pleased to learn she was

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: