|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center NEOTROPICAL HUMMINGBIRDS 2013; PROLOGUE This year for the first time, Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project recruited TWO groups of volunteers for what had become an annual nine-day expedition to study Ruby-throated Hummingbirds (RTHU) at Crooked Tree village in Belize. The first team arriving 27 February 2013 included birders, former teachers, and other adults from the U.S. & Switzerland (see last week's photo essay); this group was nicknamed "The Belize Brata." The other team--coming 11 days later--was our second consecutive undergrad student group from Keystone College in La Plume, Pennsylvania. On their annual spring break, they--logically nicknamed "The Keystone '13"--again were recruited and escorted by biology professor and bird bander Dr. Jerry Skinner.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Omega Group (team leader Bill Hilton Jr. and colleague Ernesto Carman Jr.) flew to Belize on 24 February from Managua, Nicaragua after completing the first-ever Operation RubyThroat expedition to that country NOTE: The rest of this account summarizes activities of the Keystone '13 during their eight-day trip to Belize. (Nearly all Operation RubyThroat expeditions are nine days--Days One & Nine for travel, with six days in the field separated by "Hump Day" in the middle--but the Keystoners come for eight days to accommodate timing of their spring break.) Because their schedule was otherwise the same as that of the Belize Brata who were on-site the previous week, this report for the Keytone '13 team may not repeat all the deep background related to our Belize trips; please refer to last week's photo essay for that info.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 8 March 2012 On 8 March the Omega Group once again set traps at the lodge, and once again caught a bunch of Baltimore Orioles: Five after-second-year birds (one female, four males) and four second-year birds (two males, two females). Of even greater interest was the retrapping of a female oriole (above; compare to SY-M in image just before that) because she already bore a band. Her number (2411-56749) sounded familiar so we checked our data to find we first captured this individual in the same trap at the lodge almost a year previously on 18 March 2012. As a second-year bird then she was now in her third year--and a very good example of just how site-faithful Neotropical migrants can be within wintering ranges far from their breeding grounds in North America. Such proof of site fidelity also justifies why bird habitat needs to be protected at BOTH ends of migration--to say nothing of all along the way.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps our most unusual capture of the entire time we were in Belize came when Ernesto walked through the open door of the dining room at Birds Eye View Lodge on 8 March and realized an American Pygmy Kingfisher (above) was flying around inside. Odd enough there was a bird in the building, but it was one of a half-dozen elusive species birders always seek out when they come to Crooked Tree. Ernesto moved quickly and had the bird in-hand without hurting it, after which we took numerous photos of this diminutive, 5-inch kingfisher. Because it lacked the green necklace of the female, we knew it was a male.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center While sitting on the lodge's outdoor patio, sipping cucumber juice with mint, running traps, and relaxing a bit, the Omega Group had ample opportunities to gaze across the freshwater lagoon. The water was already at least a foot lower than when the Belize Brata had come ten days previous, and the level was continuing to drop rapidly. As the lagoon dries up, fish become more and more concentrated--as do wading and diving birds that eat those fish. Most years we don't even get to see White Pelicans at Crooked Tree, but on 8 March a whole flock (above) was attracted to a school of fish less than 150 yards offshore. These massive birds with ten-foot wingspans paddle about instead of diving, working cooperatively to herd their prey into tighter schools. So concentrated, the fish are more easily engulfed by the pelicans' distendible gular pouches. (Note the head of a flopping fish in the pouch of the pelican at upper left.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As fish get crowded and oxygen content diminishes in the lagoon, some finny residents die and wash up on shore. There, three vulture species take advantage of the bounty. Most plentiful are Black Vultures (at rear above), with naked gray-black heads. Harder to see and photograph at Crooked Tree are Lesser Yellow-headed Vultures (foreground above)--which are sometimes confused with much more common and similar-looking Turkey Vultures with featherless red heads. (NOTE: Although in our image above the Black Vulture looks larger than the Lesser Yellow-headed Vulture, this is a photographic illusion; the two species are actually about the same size with a five-foot wingspan.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At mid-afternoon Bill & Ernesto visited Crooked Tree Elementary with Derrick Hendy from Belize Audubon and hung several hummingbird feeders for the students to monitor--we hope indefinitely. Staffers also helped put up a feeder at Audubon's visitor center--something we'd wanted for several years. After supper and with no group meeting to organize, the Omega Group went out after dark to look for owls. None were found, but two night creatures did appear. First was a Mexican Hairy Dwarf Porcupine (spotlighted above, and rendered in black and white) running along the aerial power line about as fast as it could move on terra firma. This species, Sphiggurus mexicanus, occurs throughout Mexico and Central America and is the nemesis of too-curious canines at Crooked Tree; we saw several dogs with porcupoine spines in their snouts. The porcupine itself--about 30" long from nose to tail tip--eats leaves, fruit, seeds, and the occasional lizard. (Note: No joke, a family of porcupines is known as a "prickle.")

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Ernesto also shined his flashlight along the roadside near the lodge, revealing bright red eyeshine. It was a Common Pauraque (above), one of the wide-mouthed goatsuckers (nightjars) related to Whip-poor-wills and Common Nighthawks. We'd always wanted to get a close photo of this species and jumped at the chance. The Common Pauraque builds no nest, laying her eggs directly on the ground. After all this noctural excitement that followed a relatively leisurely day the Omega Group actually went to bed early, getting enough rest to welcome the college group that would arrive on the morrow.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 9 March 2013

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The incoming team was our fifth for Belize since 2010 and our 21st group expedition to the Neotropics as part of "Follow the Hummingbirds North" field investigations. We are ever-indebted to our 2013 participants for field assistance and for helping underwrite expenses of the Omega Group and the overall project so our Operation RubyThroat hummingbird research in Belize could continue. (We're also grateful these camera-happy students were kind enough to share some of their Belize images as part of this photo essay, knowing we couldn't be everywhere they were all the time.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Keystone '13 team flight came in a little earlier than usual, allowing everyone to get to Bird's Eye View Lodge by early afternoon. The dining hall staff put together a tasty snack on the dining patio (above), complete with salad, freshly squeezed orange juice, finger sandwiches, and ripe watermelon to tide them over until supper. Yummy!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Meanwhile, the Keystoners excitedly explored the area around the lodge and got their initial views of birds on the lagoon. One of the first species they were able to identify were wide-mouthed Mangrove Swallows (above) that swooped around the lodge chasing insects; these graceful fliers occasionally perched on power lines, revealing big white rump patches. After supper we had our usual first-night orientation meeting and sent the team off to bed to dream of catching hummingbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 10 March 2013 Because Recia's Cashew Farm in Crooked Tree's pine savanna had been somewhat productive this year for the Belize Brata, we elected to start the Keystoners' at that study site on 10 March. After initial instruction--made easier because several students had done bird banding back home with Dr. Skinner--the team erected mist nets in lanes we had already established and marked with flagging tape the week before. At 10:25 a.m. the Keystone '13 snared their first Ruby-throated Hummingbird--a white-throated individual (above left)--so we called everyone in to the banding table where we demonstrated how to make and apply hummingbird bands, how to scribe data and take measurements (length of wing, tail, and bill), and how to evaluate age, stored fat, and wing and tail molt.

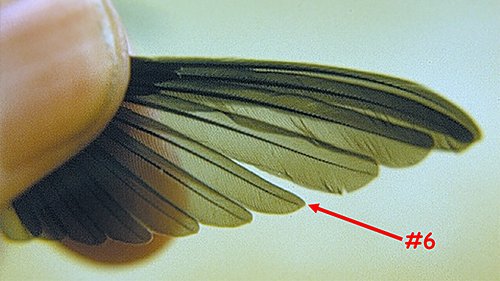

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This first RTHU lacked any red or dark throat streaking, suggesting she was female; however, one must be careful with white-throated ruby-throats because some of them are bound to be immature males. Thus, we had to confirm our in-hand bird was a female by looking at the rounded, untapered tip (above) of her #6 primary wing feather. (Male RTHU have sharply tapered #6 primaries.)

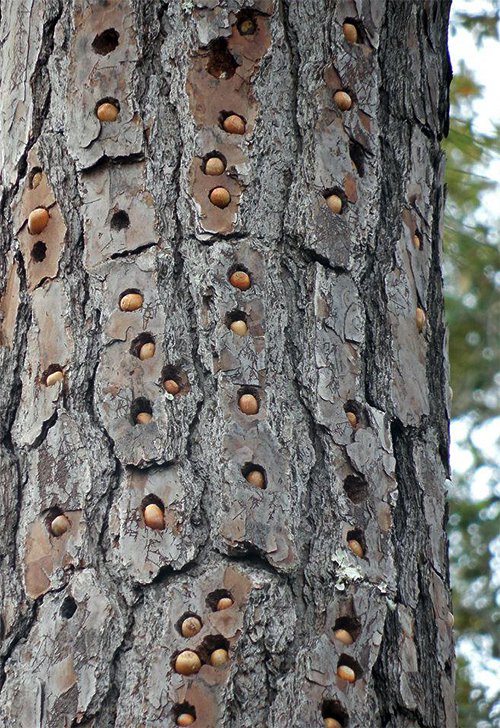

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Banding-wise, things went very slow for the rest of the morning. It wasn't until we were almost ready to shut down at noon that we caught our last two bandable birds: A male Black-and-white Warbler and a female Summer Tanager. We did get a couple of dynamite resident species, however, the most notable of which was a Acorn Woodpecker (above). The stark contrast between deep red, jet black, and pristine white on this bird is breathtaking--especially when one can examine it up close. We weren't surprised to capture this bird--there's been a resident colony of them at Recia's Cashew Farm for at least four years--but we hadn't had one in-hand since our first visit to Belize (2010). Back then we captured an adult male but this newest one was a female, as indicated by the black headband between the eyes; in males this area is bright red like the crown.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Acorn Woodpeckers take their name from their habit of collecting acorns and storing them in a larder or granary; for this particular colony it's a tall, straight pine tree at the edge of Recia's farm. The Keystoners were amazed to find this larder and to see how many holes had been drilled and stuffed with acorns--likely the result of several years of work. Such a cache indicates Acorn Woodpeckers are quite sedentary; a colony wouldn't be able to maintain and defend a larder if its members ranged widely or migrated away.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The other brightly colored bird we handled on the Keystoners' first day in the field was a Great Kiskadee (above), a large, 11-inch-long tyrant flycatcher we've seldom caught in mist nets. The kiskadee's heavy bill with a hooked tip is well-adpated to catching insects in mid-air, but the species also hunts down lizards and small rodents. Some individuals have been documented diving for fish and tadpoles, and occasionally the species will eat fruit. Although Great Kiskadees occur in open woodlands throughout their range, they're also abundant in urdan areas where they often make large messy nests on power poles. Since it was a non-migrant, we didn't band the kiskadee.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the highlights of the morning at Recia's came when the team was visited by Khadija (above), a beautiful hazel-eyed Creole girl we met on our first trip to Crooked Tree in 2010. Back then Khadija showed an immediate interest in our hummingbird work and appeared at various study sites several times through the years. It's been fun teaching and learning from her and watching her grow up.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite talking with Khadija and banding one ruby-throat, the morning at Recia's Cashew Farm was too slow for our liking. (It was also hot, and shade was hard to come by. Jackie Crozier, above, managed to find a spot out of the sun as she tended nets and recorded field notes.) Thus, we pulled all the mist nets and flagging tape shortly after noon and headed back to the lodge--already sure we would visit a different locale the next day. (We have a pet peeve to air at this point: Field researchers who leave unsightly flagging tape in place after completing their studies are thoughtless litterbugs.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Following lunch the Keystone '13 took full advantage of a "free afternoon," taking catnaps to catch up from the previous day of travel from Pennsylvania. There was still plenty of time to explore, however, and most students eagerly looked for birds and other wildlife on the lagoon or along one of the trails through neighboring woods. Nearly every resident Belizean bird was new for the newbies, so they took just as much delight from identifying the commonly seen Tropical Kingbird (above) as they did from more elusive species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center More adventurous types--half the group, actually--contracted with a local vendor for a lengthy horseback ride around Crooked Tree byways (above). Despite a nice invitation, trip leader Hilton graciously declined to mount up, having broken his ankle while riding horses on an Operation RubyThroat expedition to Guanacaste Province, Costa Rica in 2008. (It's not that the trip leader fears horses; he doesn't. It's that wife Susan has forbidden him to ride ever again, or else.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 11 March 2012 On Day Two of field work (11 March) we moved our operations to the Hurricane 2 Woodlot (above), a more forested spot where we hoped we'd be more productive than at Recia's place the day before. Indeed, by 8:50 a.m. we had our first Ruby-throated Hummingbird, another female of undetermined age; she brought the Keystoners' total to two, but that was it that day for hummers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We did capture and band quite a few other Neotropical migrants, however, giving the students opportunities to examine species they might see back in Pennsylvania when spring migration occurs. Banded birds included a Halloween-colored adult male American Redstart (above), second-year male Yellow Warbler, male Magnolia Warbler, White-eyed Vireo, Yellow-breasted Chat, Orchard Oriole & Baltimore Oriole (both second-year females), female Summer Tanager, and three Gray Catbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Every species we catch is worth examining, but perhaps the most interesting resident captured on Day Two was a little five-inch brown bird with unusual upturned bill. This was an elusive species whose common name--Plain Xenops--is about the same as its scientific epithet--Xenops minutus. In the tropical Ovenbird Family (Funariidae), this bird is related not to "our" Ovenbird (a Wood Warbler in the Parulidae) but to woodcreepers. Like the latter, Plain Xenops rambles around tree trunks, using its bill to forage for insects under loose bark or in soft, decaying wood; the unusual shape of its mandibles may allow it to pry into places other birds do not reach.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When a mist net snared a bird, a team member called out and Ernesto went running to extract it. If the bird was a new species or had some new attribute worth examining, the bander summoned everyone to the banding table for a show-and-tell session in which the Keystoners looked at the captures and identified them by working through field guides. If lots of birds were caught, there were lots of visits to the table; if not, participants spent their time making observations of local flora and fauna--especially free-flying Ruby-throated Hummingbirds that mightr be forgaing within view. In the photo above, Sara Kowalksi monitored two nets, watching activity in the Cashew tree in front of her, and studying her field guide.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the highlights of the morning had nothing to do with birds. It was the sighting of a rather large mammal--the first Collared Anteater (above) we had seen on five expeditions to Belize. This five-foot-long animal-- Tamanduas are semi-arboreal, spending as much as half their time in trees where they lap up ants and termites with their extensible 16-inch tongues. Strong decurved front claws enable them to tear open termite nests such as the large brown object in the photo above, exposing soft-bodied insects within. To keep from stabbing their forepaws with sharp claws, Tamanduas walk on the backs of their wrists. The individual we were fortunate to observe and photograph eventually climbed a nearby tree too fast for us to get another really sharp image (above left), holding on with all four legs and sometimes with its partly prehensile tail.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That afternoon the Keystoners went with Leonard to Altun Ha, the Mayan settlement that's always a memorable excursion for our Belize groups. They were met by Anne-Marie Avona (chatting in the shade, above, with Anne Elizabeth Castiglioni), an accomplished, jovial Creole woman who is internationally known for her expertise on Mayan cultures.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Going to an ancient Mayan site might seem like a touristy thing to do for an Operation RubyThroat research expedition, but because of Ann-Marie's interpretation the trip makes for an educational and thought-provoking afternoon. Besides, Ann-Marie is also a naturalist who frequently points out birds that are calling or displaying among the Mayan temples. The Keystoners, as expected, climbed one of the pyramids--Anne Elizabeth Castiglioni, Sarah Langan, and Rebecca Schulze hammed it up for the camera (above)--but from atop the towering structure they got a real feel for what it must have been like a millenium ago when 5,000 Mayans gathered in the plaza below to watch rituals at various temples.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 12 March 2012 It was partly cloudy at dawn on 12 March, a good sign it might rain later that day. Sure enough, after we ran the nets at Hurricane 2 Woodlot for a few hours we got a bit of a shower that required folks to break out their rain gear--

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Other Neotropical migrants were also active that morning, so by shut-down at noon we had banded two male Common Yellowthroats and one each of the following: Ovenbird (above), female Chestnut-sided Warbler, female Hooded Warbler, White-eyed Vireo, Yellow-breasted Chat, male Blue-winged Warbler, and after-second year American Redstart. It's interesting that all except the vireo were North American Wood Warblers (Parulidae).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Spotty rains abated during the morning and after lunch the Keystone '13 traveled with Leonard to The Belize Zoo, self-proclaimed as "The Best Little Zoo in the World." (On a hunch Bill and Ernesto stayed back to set up traps at the lodge after lunch and caught a female Orchard Oriole and--at 1 p.m.--one more female Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The latter raised the week's total to 11.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Established in 1983 "as a last ditch effort to provide home for a collection of wild animals used in making documentary films about tropical forests," the Belize Zoo houses only native species. Its main mission is to encourage Belizeans to appreciate and take care of their indigenous wildlife. The facility houses about 125 creatures, most of which would never be releasable into the wild. Kept in landscaped enclosures, animals such as the four-foot-long White-nosed Coatimundi, Nasua narica (above), are well-maintained and appear much as they would in their natural habitats. Folks are sometimes surprised to learn coatis are members of the Raccoon Family (Procyonidae). Found throughout Central America--and even wandering into south Texas and the southwestern U.S.--White-nosed Coatis are omnivorous, taking everything from fruit to road kills and small vertebrates to eggs. Like Raccoons in the U.S., they often raid trash cans in the tropics; unlike Raccoons, coatis are primarily diurnal.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among the favorite animals at The Belize Zoo are spotted Jaguars, Panthera onca (above), some of which have been reared from cubs and are quite docile. Jaguars are the largest felids in the Western Hemisphere. Although they once roamed from Arizona to Argentina, hunting and habitat destruction have decimated wild populations across that range. Belize is believed to host one of the last remaining concentrations of wild Jaguars, and just before we arrived for our first expedition this year an adult was seen on the backwaters of the lagoon--a rare sighting for Crooked Tree.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 13 March 2012 On 13 March we returned for a third day of mist netting at Hurricane 2 Woodlot, hoping to match our eight Ruby-throated Hummingbird captures from the preceding rainy day. Such was not the case, and our only RTHU was an "adult" (after-hatch-year) male with full red gorget (above) at 8:20 a.m. He did, however, make the 12th ruby-throat in four days for the Keystone '13, equalling the Belize Brata total after that group's six days in the field.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This adult male allowed us to show the group another interesting aspect of Ruby-throated Hummingbird morphology. Whereas both female and immature male RTHU have rounded tails in which rounded outer feathers are white-tipped, adult males have forked tails (above) with pointed, all-black rectrices. It makes sense that adult males would have what appeared to be more aerodynamic tails that might facilitate their courtship displays and territorial defense flights, but white tail tips in young males are harder to understand. We've always hypothesized these "female-like" feathers help immature males provoke fewer antagonistic attacks from adult males.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Any incoming feather on a bird may develop fault bars (above), which occur during stressful times. Cold weather, lack of food, and other factors can cause the feather to "stutter" as it grows, resulting in a place where the feather vane is weak from lack of barbules. In adult songbirds, wing and tail feathers are molted sequentially, so fault bars--if any--would occur in different places on adjoining feathers. However, in naked nestlings all flight feathers come in at the same time, so fault bars occur at the same place on feathers that are side-by-side. We were a tad surprised this "immature" catbird with such pronounced universal fault bars had completed the migratory trip from its natal grounds in North America because feathers often break at the faults. Had that happend with this particular bird the wings wouldn't have carried it over such a long distance.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As implied previously, catching birds in mist nets is rather like going fishing--except that we don't use any bait. Thus, there is a lot of sitting and waiting--facilitated this year by a generous contribution from the Belize Brata team that was on-site before the Keystone '13 arrived. The Brata donated several folding stools to Operation RubyThroat--devices put to good use by Travis Biely and Rebecca Schulze (above) as they waited for birds and discussed various aspects of the expedition.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Some days things can be slow at the banding table, especially if our citizen scientists aren't catching any birds in their nets. The bander uses down time to instruct the current scribe and scribe-in-waiting about the finer points of bird banding, but sometimes interesting things happen--as when an incredibly hued iridescent insect larva (above) shows up and hangs around long enough for some close-up photos with our macro lens. We're not sure exactly what kind of larva this is; at first glance we suspected Antlion but now we're thinking some sort of beetle. (If you happen to know, please send us an e-mail at INFO@hiltonpond.org.) In any case, we were stunned by the larva's brilliant colors and because of its fierce-looking mounthparts we're quite relieved the half-inch creature wasn't six feet long.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike the Belize Brata who were at Crooked Tree for nine days and had the middle of the week as "Hump Day," the Keystone '13 were present for one day less; the first and last were travel days separated by six consecutive mornings of field work. Those ambitious, energetic young folks from Pennsylvania handled such a non-stop schedule with ease, but it did mean they had to swap our usual sunrise boat ride on the lagoon for an afternoon trip. No matter, of course; there were still plenty of things to be seen on or in the water, so after lunch on 13 March everyone climbed aboard either with Leonard (above) or our friend "Tall Rudy" as our experienced, sharp-eyed captains. Because lagoon water levels had dropped about 18 inches during the preceding week, the Keystoners headed toward still-navigable Black Creek instead of the usual destination of Spanish Creek.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As always, it is quite difficult NOT to take a lot of photos on a Crooked Tree boat ride, and it's even harder to select just a few to include in this summary report. As water levels drop, bird life on the lagoon becomes almost unbelievable in number and diversity (see a small sampling of wading birds, above), and there's also plenty to look at in addition to avifauna. Following is a small sampling of images we captured as the Keystone '13 patrolled the lagoon on the afternoon of 13 March.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most frequently observed wading birds at Crooked Tree is the Northern Jaçana, so it was understandably the group's first species seen on the boat trip. These are wetland birds with elongated toes and claws that spent most of their time walking on floating vegetation or mud flats in pursuit of terrestrial and aquatic inveretebrates, small fish, and even seeds. The adult (above) has a dark head and body and a prominent naked yellow patch on its forehead. (Immatures are dorsally brown, and white beneath.) Northern Jaçanas are unusual among birds in that they are polyandrous, i.e, females have more than one mate. After copulation and egg-laying with each male, the female wanders off, leaving incubation, brooding, and chick-rearing to her various mates.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps the second-most active species observable by boat was the Snail Kite. Adult males are all dark blue-gray while females and immatures are brown with streaked breasts; young birds like the one above also have streaked heads. The species has an unusual distribution.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Snail Kites are indeed seen frequently on the lagoon, but their numbers are nearly insignificant when compared to those of the various herons and egrets that show up when water levels drop. Pristine white Great Egrets are the most abundant waders, with Great Blue Herons, Snowy Egrets, Wood Storks, White Ibises, and several other long-legged species being less abundant. One that is seen less frequently is the Tricolored Heron (above), once known as Louisiana Heron. Standing about 30" tall, the individual in the photo is in breeding condition--as indicated by the white plume (or, in French, aigrette) on the back of its head.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Somewhat smaller than a Tricolored Heron is the Little Blue Heron (above), a blue-gray-bodied 24-inch bird with purple neck and head in the adult. This species stalks its prey in shallow water by running after it.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Immature Little Blue Herons look much different than their older bretheren, being all white (above). The individual in this photo was just starting to get blue feathers on its back. Little Blue Herons are sometimes confused with other white waders but are distinguided by blue or bluish-green legs and a bluish bill with noticeable black tip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Herons and egrets are fun to watch, but the wader most folks want to see at Crooked Tree is the Jabiru--a giant stork that towers above all other birds. The adult Jabiru (above) has clean white plumage . . . black head, bill, and legs . . . and a bright red throat pouch (pale pink in immatures) . . . and it stands a full five feet tall. The 14-inch bill is slightly recurved, with upper and lower madible meeting at the tip to form a pincer used to grab eels--the Jabiru's favorite food.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We can talk about the Jabiru standing tall at five feet, but the only way to get a real feel for its size is to observe it in a mixed flock of waders (above). In the photo are yellow-billed Great Egrets, black-billed Snowy Egrets, dark-headed Wood Storks, and a Roseate Spoonbill, with a couple of Great Blue Herons in the background, and there's simply no doubt about who's bigger. With perhaps only five or six dozen Jabirus occurring in all of Belize, the Keystoners were delighted to see nearly 50 on their lagoon boat trip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Water lilies with which we're familiar typically have big, showy flowers that can be several inches across, but such is not the case with Water Snowflake, Nymphoides indica. This lily with a delicate fuzzy white flower is pantropical--i.e., originally found worldwide in the tropics--and is sometimes sold for home aquarium use. This practice led to plants being dumped into lakes and ponds in other areas; as a result--and despite its eye-pleasing appearance--in parts of Florida and Puerto Rico Water Snowflake is considered an invasive species than can crowd out native water lilies.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Water Snowflake and the tall wading birds abound on the open lagoon, but when Leonard and Rudy turned our boats up Black Creek there was a pronounced change in vegetation and animal life. Among the first birds we saw were in a big flock of Black-necked Stilts (above), whose very long pink legs allow them to forage in waters at the creek edge.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not to be too anthropomorphic, but we've always thought Black-necked Stilts to be among the most elegant of birds, with contrasting black and white plumage and a jaunty black, ever-so-slightly recurved bill. (Breeding males take on a greenish metallic sheen on the backs and wings.) The stilt's pink legs provide an unexpected dash of color.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Black-necked Stilts feeding up the creek need to keep an eye out for predators, including a healthy population of endanagered Morelet's Crocodiles, Crocodylus moreletii, that thrive around Crooked Tree. The one in the photo above probably wouldn't be a problem for a stilt; despite its gaping mouth and ferocious appearance, it was a juvenile croc perhaps 24" long. This species of crocodile is quite shy--we usually see only their eyes and nostrils as they float just below the water surface--but we heard that an adult croc attacked a fisherman in the lagoon this past year. So much for going swimming!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although we had an American Pygmy Kingfisher in-hand when Ernesto captured one in the dining room at Bird's Eye View Lodge, it's always exciting to see this tiny bird in the wild. The one above was a female--note the dark blue throat band on her otherwise orange underparts--that perched on the creekbank and led us upstream from one overhanging shrub to the next.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unfortunately, the hour was growing late and shadows were getting long, so our afternoon boat ride on the Crooked Tree lagoon had to end. On the return trip we were reminded how shallow the waters had become when Leonard ran aground temporarily and had to back the boat out with a pole he had along for just that situation. Nearby in a mudflat we could see several brown birds (above) probing the moist earth with black bills; we recognized them as Pectoral Sandpipers in breding plumage--examples that not all the lagoon's waders had really long legs.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Keystone '13 returned to shore late afternoon after a spectacular boat ride that was so intense it was as exhausting as it was exhilarating. (Note: The two 2013 boat rides on Crooked Tree lagoon were by far the most rewarding of five we've taken, mostly because water levels were so low bird numbers and diversity were quite high.) As the Keystoners got back their land legs and entered the lodge for supper, we spotted a two-foot-long snake (above) in the shrubbery just outside the front door. We're always cautious about serpents in the tropics--quite a few are poisonous--but we recognized this one right away as a harmless Checkered Garter Snake, Thamnophis marcianus, a close relative of garter snakes back at Hilton Pond. This species occurs across the southwestern and south central U.S. and into Mexico and Central America as far south as Costa Rica, frequenting areas around permanent lakes and ponds; there it eats amphibians, small fish, and earthworms. We were exceptionally pleased not a single member of the Keystone '13 shrieked or said "yuck!" at the sight of this snake, opting instead to get as close as possible for photos.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of reptiles, we would be remiss if we did not make mention of the antics of Keystoner Corey Uhrin (above), our hyperactive herpetologist who spent much his "free time" observing and catching scaly creatures. Corey observed his birthday with us at Crooked Tree and celebrated by getting very friendly with a female Black Iguana that hung out near one of the buildings at the lodge. After blowing out his candles at supper and attending the evening meeting, Corey joined the rest of the group as Ernesto led a night excursion to the western lagoon, a part of Crooked Tree island where we haven't spent much time. We had hoped to hear and even see lots of owls and nightjars, but such was not to be.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 14 March 2012 On 14 March we moved operations from the Hurricane 2 Woodlot to the Reynolds Woodlot, for educational as well as research reasons. We worked this site when the Belize Brata were present during the expedition just finished, and also ran nets there in 2011 and 2012. On the Keystoners' fifth field day, however, we anticipated a visit from by Birding Club from Crooked Tree Elementary School, and the Reynolds location was within walking distance for the kids. The morning started off and ended well, with female Ruby-throated Hummingbirds netted at 7:05, 9:05, and 10:35 a.m., bringing the Keystoners' total to 15. Nicely enough, the middle of those three birds was captured just as the birding club arrived (above), so we got to show these curious and exceedingly polite young Crooked Tree students the whole hummingbird banding procedure.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The students were--to say the least--enchanted, and one (above) even got to hold and release the hummingbird. We're always happy to host the school's Birding Club on our study sites in Belize; after all, the local kids are actually hosting US. We applaud and support the efforts of Belize Audubon's Derrick Hendy in his efforts to help the Crooked Tree community understand the importance of native and migratory birds, to say nothing of the value of protecting environment while enhancing ecotourism. Derrick likes to tell the students they can make a good living as nature guides if they will just do their school work, study their bird books, and spend time getting to know Crooked Tree habitats and organisms therein. More power to Derrick and the members of his birding club!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In addition to catching three ruby-throats and working with the Crooked Tree students, that morning we banded several other Neotropical migrants: A Gray Catbird, two second-year male Magnolia Warblers, two female Black-and-white Warblers, two Northern Parulas--a female and a second-year male (above) with a pale blue and rust neck bars. Parulas are among the smallest Wood Warblers and take a smaller-diameter band than nearly all their relatives. They breed across a large part of the eastern U.S. and in southern Canada but spend winters in the Caribbean and a very narrow band of coastal habitat from central Mexico to Guatemala. The broken eye ring is a good field mark to look for.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center During the morning the Keystoners' also caught their first Tennessee Warbler (above). Based on our work in Costa Rica where we've banded hundreds of them, we would have concluded TEWA are the most common warbler in the world. Although we've caught many fewer in Belize, they occur there in similar winter habitats to Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--not surprising when we remember the ultrafine bills of hummers and TEWA alike are used to take nectar from flowers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along with bandable migrant birds we also caught several resident species on 14 May, one of which we must include here because of its appearance. Tropical tanagers (Thraupidae) are well-known for their brilliant plumage, but we've always thought one in particular--the male Red-legged Honeycreeper (above)--outshines most. In addition to hosting school kids and catching brightly colored birds in our mist nets, all sorts of things were going on at the Reynolds Woodlot that morning. The following photos depict some examples.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A large-headed red ant (above)--undoubtedly a soldier of an unknown species (a Leafcutter, perhaps?)--seemed very irritated with a dead tendril wound around a twig. The ant attacked the corkscrew growth several times, using massive serrate mandibles to chew through in short order. We were glad this powerful little insect hadn't chosen to clamp down on anyone's fingers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of ants, a column of Army Ants made its way through one corner of the woodlot, stirring up insects, small mammals and lizards, and just about anything else in their path. Numerous tropical bird species have learned to take advantange of this phenomenon and swoop down after those hapless creatures scattering away from the Army Ants. That morning a family of Groove-billed Anis were as opportunistic as possible, animatedly hopping and flitting through the grass in pursuit of prey items.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Yet another kind of insect came into view when one of the Keystoners accidentally stepped on a rotten tree trunk near the banding table. Instantly a swarm of pale brown wingless insects began running about in all directions; it was a termite colony (species unknown). The Collared Anteater from a few days before would have engulfed them all with gusto. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we looked more closely at our photo of the termite swarm we realized there were at least two castes represented. The majority looked more or less like the rotund one above left, and we supposed those to be workers. Members of this caste spend most of their lives chewing wood and digesting it courtesy the microbes in their guts--all so they can feed larvae and care for the queen. A few smaller individuals (above right) had what looked like pointy heads; these were soldiers whose role is to protect the colony. The complex behavior of social insects such as these termites is certainly one of the great wonders of nature.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With morning bird banding slowing to a crawl, the Keystoners pulled the nets at noon and returned to the lodge for lunch and an unstructured afternoon. When lodge manager Verna went to her nearby home for a break, she called back to Bird's Eye View with news there as a big turtle in her backyard, so several of us went to investigate. It turned out to be a Mesoamerican Slider, Trachemys script venusa--probably the same subspecies the Omega Group had seen a few weeks earlier in Nicaragua. Verna's turtle was indeed large, with a carapace at least 18" long.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sliders are water turtles, so we could have guessed what this particular reptile was doing on land a couple of hundred yards from the Crooked Tree lagoon: She was a female and she was nesting--placing two-inch oblong eggs (above) in a vase-shaped cavity she had excavated with her hind claws. As in all reptiles, aquatic turtles must lay their eggs out of the water, lest the embryos drown. The leathery eggs of turtles are somewhat permeable, so on land oxygen flows freely to the developing turtle. Eggs of reptiles and birds are really their own private aquatic habitats--as are the wombs of mammals.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 15 March 2012 With only one more opportunity to mist net birds, the Keystone '13 group was especially enthusiastic on 15 March. Nearly all were up and dressed well before Ernesto's customary door knock, so we got into the field in short order. Returning to Reynold's Woodlot, the team deployed nets and at 6:55 a.m. caught one last female Ruby-throated Hummingbird--number 16 for the week. The morning brought in a few other Neotrops, including some the group had not yet handled in Belize: Male Black-throated Green Warbler (above), Tennessee Warbler, Red-eyed Vireo, Northern Waterthrush, female Summer Tanager, Least Flycatcher, and Yellow Warbler.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Things were still a bit slow bird-wise on the Keystoners' last day in the field, providing opportunity to check over field notes and explore some of the vegetation around the Reynolds Woodlot. One little inch-long red flower (above) was of particular interest--especially when some students saw it being visited by a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. The star-shaped scarlet blossom surrounded by fern-like foliage was Cardinal Climber, Ipomoea multifida, a member of the Morning Glory Family (Convolvulaceae). We were pleased to see this half-inch flower in the wild, in part because we list it among Operation RubyThroat's "Top Ten Exotic Hummingbird Plants" that attract ruby-throats in gardens back home.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Nearby, a second five-petalled pink flower (above) was much larger than the Cardinal Climber. We're not sure of the species or even if it's a Belizean native, but it had the familiar structure of a hibiscus--a member of the Mallow Family (Malvaceae). Note the dark red flower center--a so-called "bee guide" that causes the insects to brush past pollen-laden stamens to get to the nectar reward at their base.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A third blossom worth mentioning was another with a pinkish-purplish hue, but the flower (above) was much more ornate. This was one of the tropical Passionflowers, Passiflora urbaniana, known locally as "Grandpa Balls." This prolific vine grows throughout Belize and the Caribbean, where it reportedly is visited by small hummingbirds. We've not been able to confirm this phenomenon during our work. At the end of the morning the Keystoners pulled the nets--and flagging tape--before a return to the lodge and an afternoon of packing and exploring. That evening at the Farewell Fiesta we reviewed the team's work for the week. (Summary results are included at the end of this photo essay.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 16 March 2012 We wouldn't say the Keystone '13 team (group photo above) was eager to return to cold weather and snow in northern Pennsylvania, but the particpants WERE up bright and early despite a night of staying up late and "reminiscing."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As their expedition came to a close, the Keystone '13 gathered outside the office at Birds Eye View Lodge (above), turned in their keys, and bid adieu to the helpful staff. The Omega Group waved farewell as Leonard took the crew and their luggage back to Belize City for the flight home. Afterwards, despite running four Dawkins traps in the garden for several hours the Omega Group caught no additional birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center 17 March 2012 Dawn broke on 17 March with the usual awesome sunrise over the lagoon (above). Bright and early the Omega Group (Bill & Ernesto) finished the task of stowing net poles and other bulky equipment Bird's Eye View Lodge is kind enough to hold for us year-to-year. It's quite convenient not to have to lug all this stuff to Crooked Tree each winter, or to buy it anew with every field expedition to Belize. Fortunately the Dawkins traps collapse and mist nets fold into plastic bags, but there's still one suitcase chock full of gear to transport back to Hilton Pond Center--plus clothing, personal items, laptop conputer, iPad, LCD projector, and camera bag. Ah, the wonders of field equipment in the digital age! (The good news is there's usually extra suitcase room on trips home because we hand out spiffy new Operation RubyThroat T-shirts to expedition participants who ordered one. We're SO proud if they wear them on the plane home!) The Omega Team wandered around the lodge property on 17 May as breakfast was being prepared. Ever eager for one more photo they each pulled put a Canon SX50--a relatively compact higher-end point-and-shoot with a 1200x optical zoom lens they'd been field testing in Belize. (Most close-up photos on this page were made with a 60mm macro lens mounted on a full-sized Canon 7D digital SLR, but all that was already packed away for the flight home.) The trip leader wasn't disappointed with the SX50--although it's sometimes frustratingly slow to focus--and got the following series of acceptable shots of Vermilion Flycatchers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Vermilion Flycatchers have a disjunct distribution, occurring from extreme southwestern U.S. into Mexico and Belize but only in scattered parts of Central America. (We never see them in Costa Rica.) Then they occur again in northwestern South America and south to Argentina. Even more perplexing is a population--arguably a different species--that breeds in the Galapagos Islands. No matter where you find them, adult males (above) are striking in appearance with brown back, wings, tail and mask contrasting sharply against an almost indescribable bright red (vermilion) crest and underparts.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although there are always a couple of male Vermilion Flycatchers around Bird's Eye View, it appears the most dominant one gets to lay claim to a territory that includes the safety and bounty of the lodge garden. This individual patrols the grassy area around the buildings but also gets to go on forays into an adjoining pasture that supports abundant insect life, i.e., lunch. Each year this male--or one who holds the same territory--attracts a female (above) that by the time we leave Belize in mid-March is either building a nest or sitting on eggs. The female is much less colorful than the male, grayish above, with a breast streaked in black; a peach belly and undertail coverts are the only things that keep her from being completely drab. In the photo above, the female was looking for nesting material, paying close attention to the plant just in front of her.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That plant happened to be Scarlet Milkweed, Asclepias curassavica (above). This native species has hues reminiscent of Lantana--a flower with which it is often confused. As in North America, milkweed is a favorite host plant for larvae of Monarch butterflies--although the Belizean Monarch population breeds year-round and migrates only short distances from highland to lowland habitats and back. Scarlet Milkweed's blossoms were about as bright as feathers on the male Vermilion Flycatcher, but his mate wasn't at all interested in the plant's flowers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center No, the female Vermilion Flycatcher wasn't attracted by milkweed flower clusters but by the plant's seed pods, some of which had just ripened and broken open (above). The flycatcher didn't actually want those seeds, either; she had her maternal eye on the soft silky hairs attached to them--hairs that help milkweed seeds float away on the wind OR that would make a mightly fine lining for a flycatcher nest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Next thing we knew the female Vermilion Flycatcher was grabbing a milkweed seed with her bill, nipping off the fine hairs, and flying with them to the crotch of a nearby tree (above). There, under the watchful gaze of her mate, she fashioned a soft cup of milkweed hair--a perfect repository for eggs she undoubtedly would begin laying sometime very soon.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Having chronicled the behavior of nesting Vermilion Flycatchers, we made the rounds of Bird's Eye View Lodge to tell everyone on staff how appreciative we were of their work. After one last look at a couple of giant Jabirus (above) flying powerfully but gracefully over the lagoon, trip leader Bill Hilton Jr. and indispensible guide-colleague-coworker Ernesto Carman Jr. boarded Leonard's van once again for an hour-long ride to Belize's international airport. Counting this year's Nicaragua expedition and two successive ones in Belize, the Omega Group had been going pretty much non-stop for 32 days . . . and it was finally time to go home to Hilton Pond and Finca Cristina.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center BELIZE BIRD BANDING SUMMARY During the period 9-16 March 2013 "The Keystone '13" from Keystone College (La Plume, Pennsylvania) spent six five-hour mornings running mist nets and/or live traps at Crooked Tree village in north central Belize as part of Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project; the Omega Group also ran traps on 8 and 17 March. Together the young citizen scientists captured and helped band a total of 16 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, Archilochus colubris. Included in those captures were two adult males (with complete red gorgets), a second-year immature male (with incomplete gorget), and 13 white-throated females (above) of undetermined age. (The combined total for both of this year's Belize expeditions was 28 RTHU, including four adult males, one second-year male, and 23 females. This preponderance of female ruby-throats is typical for our mid-winter work in Central American countries.) During our five expeditions to Belize since 2010 we have banded 111 RTHU.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were our usual target species (left leg of a banded male, above), during our second Belize 2013 expedition The Keystone '13 and Omega Group incidentally mist netted or trapped another 46 Neotropical migrants of another 21 species. To the latter we applied bands from the U.S. Bird Banding Laboratory in the hope they would be encountered back on the breeding grounds in North America. Non-hummingbirds banded included:

The combined total for both this year's Belize expeditions was 28 Neotropical migrant species and 150 individuals, including our 28 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We also mist netted numerous resident Belizean birds; we examined and photographed these non-migrants (see write-up above) but did not apply U.S. bands. Two of these were hummingbirds: Rufous-tailed Hummingbird (above) and Green-breasted Mango. The Keystone '13 recaptured two birds with U.S. bands we had applied in previous years in Belize. These individuals showed strong site fidelity, usually being recaptured within a few yards of their original encounter.

The Keystone '13 observed (sighted or heard) an incredible 123 species of free-flying wild birds during their stay in Belize, including those encountered at Crooked Tree, Altun Ha, the Belize Zoo grounds, and elsewhere. Numerous other vertebrate and invetebrate animal species were also observed and photographed, as were many kinds of native tropical flora. We look forward to mounting a follow-up Operation RubyThroat expedition to Belize in March 2014, returning to Crooked Tree and Bird's Eye View Lodge with another Keystone College group. Operation RubyThroat: the Hummingbird Project is a research, education, and conservation initiative of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History in York, South Carolina USA. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All contributions are tax-deductible on your

NOTE: Info about 2014 citizen science expeditions to Belize and Nicaragua will be posted within a few weeks. In the meantime, you might consider joining us for our next Operation RubyThroat adventures in November 2013 at Lake Atitlán (southwestern Guatemala) or Ujarrás (Costa Rica's Caribbean slope). Details are at 2013 Tropical Trip Announcements. Summary reports for past trips are linked from the table below.

|

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

As always, our Keystoners would enjoy the hospitality and amenities of

As always, our Keystoners would enjoy the hospitality and amenities of

On the morning of 9 March the Omega Group did a little more scouting for possible study sites and then headed out with trusted guide and driver Leonard for Belize's international airport. About the same time, 12 incoming participants of our second 2013 Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expedition to Crooked Tree were boarding United flight 1657

On the morning of 9 March the Omega Group did a little more scouting for possible study sites and then headed out with trusted guide and driver Leonard for Belize's international airport. About the same time, 12 incoming participants of our second 2013 Operation RubyThroat hummingbird expedition to Crooked Tree were boarding United flight 1657

By 8:40 a.m. we had the first bird in-hand--a second-year female Yellow Warbler

By 8:40 a.m. we had the first bird in-hand--a second-year female Yellow Warbler

It is distinguished by a big head striped in black and white, with a yellow crest that is usualkly hidden. When perched

It is distinguished by a big head striped in black and white, with a yellow crest that is usualkly hidden. When perched

also known as Northern Tamandua,

also known as Northern Tamandua,

not all that common an occurrence during the dry season in Belize. Keeping field notes, cameras, and binoculars from getting wet is important--as demonstrated above by a very conscientious Sarah Langan. Despite having to temporarily close the nets, we had a pretty good morning of banding with EIGHT Ruby-throated Hummingbirds captured between 8:05 and 11:10 a.m., including six females, a second-year male

not all that common an occurrence during the dry season in Belize. Keeping field notes, cameras, and binoculars from getting wet is important--as demonstrated above by a very conscientious Sarah Langan. Despite having to temporarily close the nets, we had a pretty good morning of banding with EIGHT Ruby-throated Hummingbirds captured between 8:05 and 11:10 a.m., including six females, a second-year male

Prior to the ruby-throat capture, the Keystoners actually caught our first bird at 6:50 a.m.--a second-year male Yellow Warbler--followed soon thereafter by male and female Black-and-white Warblers, a female American Redstart, and a couple of Gray Catbirds

Prior to the ruby-throat capture, the Keystoners actually caught our first bird at 6:50 a.m.--a second-year male Yellow Warbler--followed soon thereafter by male and female Black-and-white Warblers, a female American Redstart, and a couple of Gray Catbirds

It occurs in the Evergaldes--where it's considered endangered--and occasionally shows up in the Rio Grande Valley. Distribution in the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America is spotty, with the greatest concentration of breeding birds in costal and inland Brazil. The Snail Kite feeds almost exclusively on

It occurs in the Evergaldes--where it's considered endangered--and occasionally shows up in the Rio Grande Valley. Distribution in the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America is spotty, with the greatest concentration of breeding birds in costal and inland Brazil. The Snail Kite feeds almost exclusively on

His intense blue bib and nape contrasting with a turquoise crown and jet black body and mask make for a very striking image.

His intense blue bib and nape contrasting with a turquoise crown and jet black body and mask make for a very striking image.

As always, the Keystone group was recruited and led by Dr. Jerry Skinner

As always, the Keystone group was recruited and led by Dr. Jerry Skinner

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: