|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

UJARRÁSCALS IN COSTA RICA: PREFACE I was at Hilton Pond Center the first few days of November but spent most of that time preparing for our upcoming Operation RubyThroat expedition to study hummingbirds in Costa Rica. While still at home in York I finished the bulk of demolition and reconstruction work on a Teaching/Learning Platform behind the old farmhouse, observed a few birds, filled sunflower seed feeders, and in general got things in order before packing for our ten-day out-of country trip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our proposed November 2014 excursion to the San José region caught folks' attention as soon as it was announced--so much so we added two slots to bring group size to 14. This is the absolute maximum for our Central American trips designed for lots of hands-on activities and one-on-one learning. Operation RubyThroat trips aren't the cheapest you will find, but we guarantee an intensive, enjoyable, unforgettable learning experience for each and every participant. Our citizen scientists come from across the U.S. and Canada--once a woman traveled from Switzerland to participate--and very few of them consider themselves "expert" birders. Most are simply interested in natural history and want to help with our on-going quest to learn more about what Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are doing during "winter" months when they're not coming to backyard sugar water feeders in eastern North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This latest Costa Rica expedition was our 22nd to Central America since initiating the first--and still only--long-term study of ruby-throats on their wintering grounds. Wife Susan and I departed Hilton Pond and the Charlotte airport on 4 November, changed planes in Miami, and dropped into San José late evening. This write-up is submitted as an official record of our nine-day trip and in appreciation for support provided by the participants who made it all possible. I also acknowledge use of several photos made by group members who documented activities while I was banding birds and in teaching mode. Since I didn't photograph every bird we handled in 2013, I've also incorporated a few images from my file of birds captured on previous Operation RubyThroat expeditions to the Neotropics. BILL HILTON JR. • PRE-ARRIVAL ACTIVITIES • After meeting at the San José airport late on the evening of 4 November, Ernesto drove the Hiltons two hours east through Alajuela, San José, and Cartago, eventually getting to Finca Cristina--'Nesto's childhood home at Paraíso.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After breakfast Linda pointed out a hairy two-inch-long spider (above) in a laundry basket and asked us to snap a few photos. She thought it might be one of the small tarantulas, but we were unable to confirm an identification. (If you know the species, send us an e-mail at info@hiltonpond.org.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our most tedious and time-consuming pre-group task was to drive back into San José for a meeting with a conservation officer to sign scientific research permits and other documents required of us by the Costa Rica government. We also met with Paulo Valerio, Holbrook Travel's in-country coordinator who provides invaluable assistance in making local arrangements for our excursions. Later we were pleased to connect again with Juan Diego Vargas (above right), Ernesto's closest tico friend and professional colleague. JuanD, a graduate student in ecotourism, has helped out on several hummingbird expeditions and filled in admirably for 'Nesto when he was unable to attend our 2012 Operation RubyThroat trip to Belize. Accompanying JuanD was Diego Quesada (above left), another enterprising young Costa Rican naturalist we were glad to meet. After returning to Paraíso by late afternoon we drove down the mountain to Ujarrás to scout Chayote fields for hummingbirds and make meal arrangements at Bar Y Restaurant El Cas, a perfectly situated outdoor restaurant where we'd be taking most breakfasts and lunches after trip participants arrived. It appeared not many hummers were feeding on Chayote nectar or on sugar water at El Cas--but it WAS nearly dusk and they might already have settled down for the night. Or so we hoped. • DAY ONE: The Adventure Begins •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Three participants (above) had arrived the evening before to make connecting flights, so we first picked them up from area hotels and then went off to the airport to meet the rest of our citizen scientists. In alphabetical order, the 2013 Ujarrás team included: Kathy B. (Whitehouse Station NJ); Leslie Bergum (Carroll NH, above right); Ethelyn Bishop (Laurel MD, above left); Sharon Groves & Phil Seward (Albany NY); Dave & Jan Jezyk (Wilmington DE); Jenine Pontillo (Pomona NY, second from right, above); Judy Schwarzmeier (Eau Claire WI); Mary Siebel (Oregon WI); Jim Shuman (Morristown NY); Pat Thompson (Kensington MD); Gary & Mary Wolf (Wellesley MA); plus the Hiltons, Ernesto, and the driver. That made 18 people--a fortunate number since there were only 19 seats on the bus. (NOTE: Judy Schwarzmeier actually didn't show up at the airport; she had missed her Minneapolis-Atlanta-San José connections because of TWO dysfunctional aircraft and would arrive on a much later flight.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After clearing customs and immigration and loading luggage on the bus, the team stopped at the airport restaurant (above) for a late post-flight lunch prior to departure for the Lodge. On the menu, of course, was the group's first taste of black beans and rice--a Costa Rican staple.

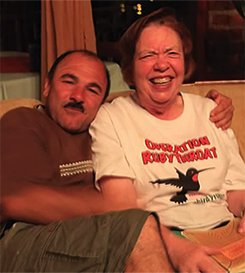

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All our 2013 team members proved to be important, but we have several marginal comments about some individuals who trip leader Hilton and/or Susan Hilton knew from other venues. For example, Dr. Jim Shuman is a life-long friend (49 years!) and collaborator; Hilton met him in 1964 at West Virginia's National Youth Science Camp. (Photo above of Dr. Shuman and the Hiltons is from an NYSC luncheon at the famous Greenbrier Hotel in the mid-1970s; somehow, this historical/hysterical image kept showing up later in the week during evening presentations by group members. Incidentally, Jim is the godfather of son Billy Hilton III and was officiating minister when Billy got married; he's also president of Hilton Pond Center's board of trustees.) Among other connections, we knew Mary & Gary Wolf from their attendance at several annual sessions of the New River Birding & Nature Festival in Fayette County WV (where 'Nesto and Hilton serve as guides). A few participants had heard Hilton speak at a native plant symposium in Millersville PA, while others knew about ORT expeditions through Holbrook's Web site or by searching on-line and serendipitously coming across our Neotropical Trip Descriptions. One citizen scientist even signed up after she saw Hilton in a hummingbird presentation telecast on Wisconsin ETV. Lastly, our token "groupie" who had been on two previous Operation RubyThroat excursions was Ethelyn Bishop--an alumna of Costa Rica-East 2012 and Ujarrás 2011 and the only one of our 160-plus veterans to repeat an ORT trip to the SAME destination. (Talk about site fidelity!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even though most members were "strangers" to each other the group bonded almost instantaneously--a bond that grew and broadened throughout our nine days together in Costa Rica. In fact, participants were already using binoculars and building the birding checklist while we were still in the airport parking lot (above). The two-hour bus trip to our lodge gave us plenty of time for introductions while Ernesto helped folks get oriented with insightful comments about flora, fauna, habitats, Costa Rican culture, and even geology. We could hardly avoid the latter with the massive Irazú Volcano (190 square miles) looming over us for the entire ride. As we made our way eastward, 'Nesto used his cell phone to check in with Juan Diego from time to time as he and Diego scouted the Chayote fields and El Cas restaurant feeders at Ujarrás. JuanD reported a few Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, but not nearly as many as we had observed (and banded) in years previous.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although this apparent dearth of ruby-throats was not good news, we didn't alert our trip participants on the bus; no sense being pessimistic and dampening their nearly unbounded arrival-day enthusiasm. We also didn't tell the group JuanD was able to spot at least one adult male RTHU. In fact, after getting a high-res image of the bird with his SLR camera and telephoto lens, JuanD took a cellular phone photo of the camera's magnified viewing screen (above) and e-mailed it to 'Nesto's phone. Upon receipt the Hiltons and 'Nesto were secretly ecstatic to see a band on the bird's left leg--a likely sign it was one of ours from years past because other hummingbird researchers typically place bands on the right.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By late afternoon the loaded bus had passed through Paraíso and started the long downhill into Orosi Valley and our destination: Tapanti Media Lodge (above)--our home for the duration of the expedition. We stayed at this facility on previous Operation RubyThroat trips and found the rooms to be comfortable (i.e., acceptable beds AND hot water showers!). Even better, the food was always tasty. The only disadvantage was Tapanti Media Lodge sits in a valley two mountain ridges away from our study site, requiring a 25-minute bus ride to Ujarrás each morning. (On the plus side, roads were good and we got that much more time en route to watch birds, sunrises, and tropical scenery.) After folks checked in we had a tasty buffet supper, followed by our usual first-night orientation meeting that included a history of Operation RubyThroat research in Costa Rica. We also challenged the group to come up with a memorable nickname to set them apart from the previous 21 expeditions we'd taken to the Neotropics. (Until a suitable submission, they would be known only as "The Unnamed." Eventually they'd have a distinguished moniker like the pioneering Ujarrás "Chayoteers" from 2011 or the "Chayodoce" team from 2012.) After a long day of travel everyone got to bed by 8:30 p.m. or so--except for a somewhat bleary-eyed Judy Schwarzmeier, who finally arrived near midnight via taxi after missing her scheduled flights earlier in the day.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY TWO: The Adventure Continues • Shortly before dawn on 7 November trip leader Hilton made the rounds of Tapanti Lodge, rapping woodpecker-like on each door to waken the team. Our group occupied ALL the Lodge's rooms, so we pretty much had the run of the place. Within 30 minutes team members were (mostly) awake, dressed, aboard Alvaro's bus with field gear, and heading toward Ujarrás for breakfast and their initial visit to the study site. Our first stop on each field day was El Cas (above), a rustic outdoor restaurant where Andrea and family prepared us with a tipico--the traditional Costa Rican breakfast of scrambled eggs, fried plantain, farmer's cheese, fresh fruit and juice, and those nearly ubiquitous black beans and rice. Ingredients were always about the same, but the talented El Cas cooks always made things taste new and different day-to-day.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Andrea and her family prepared our breakfasts buffet-style, allowing us to serve ourselves, eat, and depart quickly enough to maximize hours in the field. That said, there was always time for a cup of coffee for caffeine-dependent members of the group. Typically, the wake-up beverage was brewed from freshly ground Café Cristina medium roast brought from home by Ernesto.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Following breakfast we took the short drive from El Cas to a nearby Chayote field--Plot 3--which was only about a three-minute trip. We monitored and banded Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in this particular five-acre field during our first two years at Ujarrás and considered starting out there again in 2013. Alas, based on scouting reports from Juan Diego and what we could see this first morning in 2013, there were almost no hummers in Plot 3 AND the foliage in its Chayote arbors was so dense it would have been difficult to run mist nets. Plot 3 was by now what we might call an "old" Chayote field; i.e., vines had been in place for at least three years--about the limit for good productivity--and therefore due for replacement. Instead the group walked on toward Plot 4, a partly sloped field (above) on the other side of a stream that bordered the plantation. There we saw numerous hummers--including ruby-throats--and decided to erect mist nets at this location, which we also had used in 2011 and 2012.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first field day is always the hardest because we have to bring group members up to speed on how to attach uncooperative and somewhat delicate 12-meter-long mist nets (above) to 10-foot-tall poles and deploy them under the Chayote canopy. This is a simple operation after one has done it several times, but on day one everyone felt like they were all thumbs.

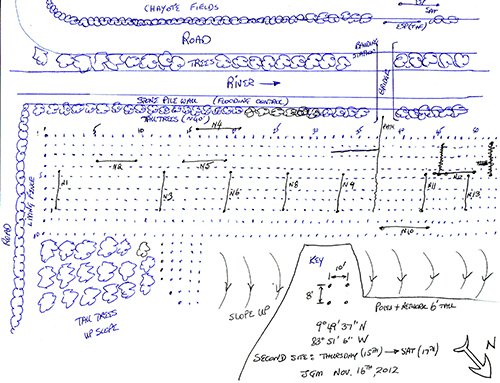

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Again, because Plot 3 was overgrown and appeared not to be hosting very many hummers, we elected to begin our 2013 work at Plot 4. Last year's net deployments of this site were recorded in great detail on a map (above) by Gavin MacDonald, one of our truest Operation RubyThroat "groupies" who with wife Mary Kimberly has been on FIVE of our expeditions. (We know them both well and have visited their home in Decatur GA.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Running mist nets is difficult enough in an open area, but when one has to contend with a layer of Chayote leaves held up by a grid of wire about seven feet off the ground things become even more difficult. We showed the group a little trick we devised in which we poke a net pole up through the vegetation and fix it in place with a loop of wire attached to the overhanging superstructure (above). This technique works well, even though we can only open three of four horizontal net shelves because of restricted height. Despite not utilizing 25% of available net, we've still been able to catch birds under the arbor. Working in teams of two (or three or four on the first day), folks worked quickly at erecting nets beneath the Chayote.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a net was up it stayed under more or less constant surveillance by one or more net tenders. When there was a capture (above), someone yelled out "Bird!" and Ernesto or one of the trained extractors in the group went running to remove it. The bird was placed in a zippered white lingerie bag for transport back to the banding table for processing.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At various times during the morning we called in the group for "show-and-tell." This usuakky occurred when we'd caught a new species--whether a bandable Neotropical migrant or an unbandable resident. Trip leaders seldom told folks what species of bird was in-hand, requiring them to work through the field guide to figure it out for themselves. This was always a great learning experience that sticks much longer. It was also a time for close examination and hand-held bird photography.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On the first day in the field the first bird was banded in front of the whole group so everyone would understand the procedure. A scribe-in waiting (AKA "scribesmaid"; in this case Judy Schwarzmeier in blue, above) sat to the bander's right, brought birds to the table, and made note of the time and net location for each capture. The scribe (Pat Thompson, to the bander's left, above) recorded these data, as well as info about the bird's band number, species, age, sex, and molt condition. The scribesmaid then weighed the bird with a spring scale prior to release.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first bird netted at 8:30 a.m. on our first day in the field (7 November) was NOT a Ruby-throated Hummingbird but one of those nearly omnipresent Tennessee Warblers (file photo above)--our most commonly caught Neotropical migrant on both previous expeditions to Ujarrás. Their presence among Chayote ought not be surprising in that TEWA, like hummingbirds, frequently take nectar--a behavior facilitated by this warbler's very thin and pointed bill. (Not coincidentally, we also caught numerous TEWA when they were nectaring from Aloe Vera flowers in Guanacaste Province on Costa Rica's Pacific side.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Tennessee Warblers that cross our banding table in Costa Rica show every imaginable color variation, from the gray crown of adult males (file photo, above left) to bright yellows typically found on younger birds--especially females. In 2011 at Ujarrás we banded 93 TEWA (out of 155 total bandings of all species), and last year handled 104 (out of 184). During both previous field seasons in the Chayote we netted and released many more TEWA than we had time to band, so we anticipated a similar situation for 2013. Oddly, we banded only one new Tennessee Warbler our first day this year, but at 9:10 a.m. we captured another TEWA bearing a band that looked a little dull. (New aluminum bands are quite shiny.) A quick check of our records showed we first caught this bird (#2090-30029) two years previously on 14 November 2011 in the very same Chayote Plot #4; it was scribed and released after banding by Chayoteer Nancy Meier. Since Nancy had recorded it as an immature male in 2011, it was now classified as a third-year bird that must have made a round-trip to its North American breeding range and back to the Neotropics two times. Based on plumage and its rather long wing chord, we had determined this bird to be a male; 2013 measurements confirmed that determination. Amazingly, the group caught two more "old" Tennessee Warblers that first morning. One was #2090-30835 (banded 11/15/12, now a second-year female; scribed by Kathy Roggenkamp) and the other #2090-30852 (banded 11/16/12, now an after-second-year male; scribed by Phil Marino). These two birds also had been caught in Plot #4 and returned to be recaptured there. Talk about site fidelity!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our 2013 citizen scientists were already making great headway with the capture of three returning Tennessee Warblers, but at 10:30 a.m. they added another bird to the list of site-faithful species when a previously banded Mourning Warbler (#2450-90935) got snared in a net. We'd only banded four MOWA in our first two field seasons at Ujarrás, and this one happened to have been captured on 13 Nov 2012. He was an immature male back then (as scribed by Anne Beckwith), so now he was officially a second-year bird. (We joked this Mourning Warbler seemed to be only a "little" lost; he had been banded in Plot #3, which immediately adjoins Plot #4.)

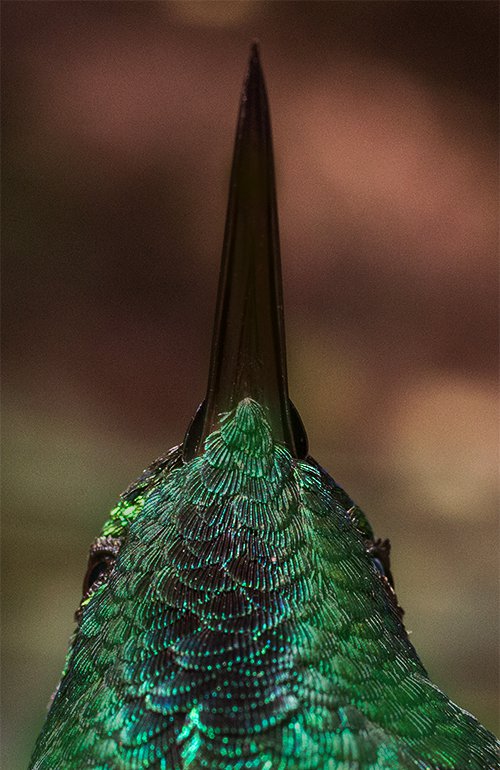

At 10:50 a.m. we got a more-excited-than-usual call from within the Chayote thicket: "Bird! It's a ruby-throat! This was good news, of course, since Ruby-throated Hummingbirds were the real reason for our being in Ujarrás in the first place. Sure enough, when the lingerie bag came in it contained an adult male RTHU with full red throat plumage (file photo above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Banding hummingbirds is a whole 'nother matter from banding other birds because each band must be cut, polished, formed, and fitted to the bird's leg (above). A ruby-throat's leg is about the same diameter as the wire on a diaper pin, so we're talking about tolerances of a fraction of a millimeter when cutting the band to proper size.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Prior to release, we offered the hummingbird a drink of water for his troubles and marked him with temporary blue dye (see file photo above). This non-toxic coloring wears off after 4-6 weeks and allows us to make observations about hummers we've already banded. (NOTE: We use a similar color marking procedure in each Central American country where we band; Orange for Nicaragua, Black for Guatemala, Purple for Belize, Blue for Costa Rica. We also mark with Green at Hilton Pond Center, so it's entirely possible you could encounter a color-marked RTHU at your feeder next year after we've banded it somewhere. If that happens, please contact us immediately at research@hiltonpond.org. Note that yellow on a hummer's throat is probably pollen.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our only other new capture of a Neotropical migrant on our first day this year was a Northern Waterthrush (file photo, above), but we did catch some other unbandable birds. Most of these were brand-new to our North American group participants and required quite a bit of page-flipping in the Costa Rica bird guide.

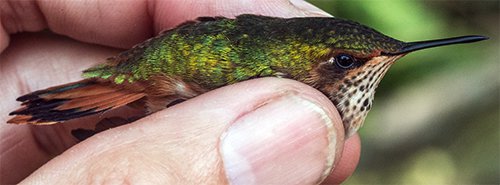

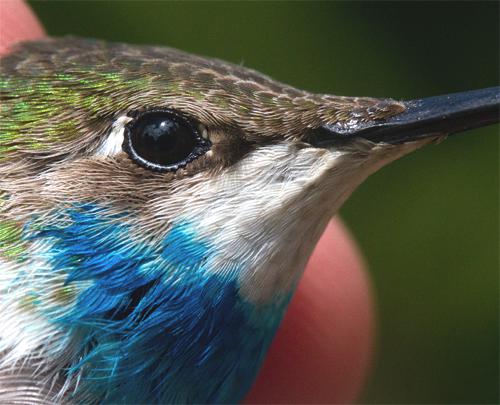

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The resident species perhaps of greatest interest to the group was a tiny hummer about two-thirds the size of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird; it could only be a Scintillant Hummingbird (above), the smallest of Costa Rica's 51 trochilids.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At first glance we thought it to be a young male Scintillant Hummingbird but Ernesto reminded us it was a Selasphorus species (S. scintilla). This genus includes Rufous Hummingbirds (S. rufus) that breed in northwestern North America and show up frequently as winter vagrants in the eastern U.S.; Selasphorus females typically have several randomly scattered metallic gorget feathers, as shown in the photo above of our just-captured bird.

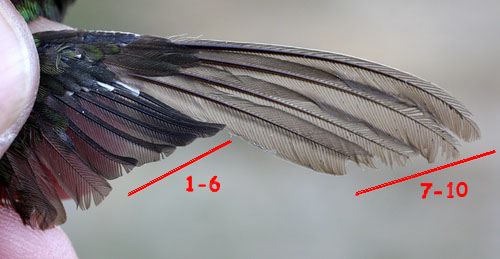

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although immature male Scintillant Hummingbirds resemble females, they can be sexed in any plumage by examination of the outer (#10) lead primary. In our bird, this feather was broad and more or less rounded at the tip (above); in males, the #10 is narrower and more pointed.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Scintillant Hummingbird is endemic to Costa Rica and western Panama, where the male (above, from a previous expedition) flashes his brilliant golden-red gorget as a way to attract less-colorful females. Note that unlike ruby-throats, the Scintillant's gorget flares out at the sides, making it seem exceptionally large for such a small individual.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center When all had a chance to examine and photograph the minuscule Scintillant Hummingbird, Jim Shuman--tallest member of this year's group--was selected to release it. Needless to say, the size difference 'twixt hummer and human was quite noticeable. We caught but did not band two other hummers that first day: Rufous-tailed (by far the most common trochilid in Costa Rica) and Steely-vented Hummingbird. This already brought our 2013 hummingbird species total to four.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Shortly after noon we finished our work at the banding table and called out for folks to shut their mist nets and bring them in for loading. Taking nets down is just as tedious as erecting them, but the crew got the hang of things pretty quickly and we were off for a buffet lunch at El Cas by 12:30 p.m. When we arrived we quickly hung four portable Dawkins-style hummingbird traps and into each moved one of the feeders Andrea faithfully maintains to attract hummers for us. These traps are collapsible plastic mesh cylinders (above) with no moving parts--just a door that stays open to allow hummingbirds to enter and feed. After eating the hummer forgets how to exit and flies up to the top of the trap, just as hummers sometimes do when getting snared in a garage with an open door. In the case of the Dawkins trap, one simply inserts a hand through the open door and gently grasps the somewhat disoriented bird. It works pretty well on hummingbirds until they figure it out, which means you may only get one chance to trap any particular hummer.

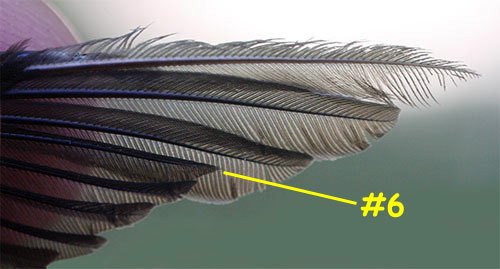

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite the Dawkins traps' unpredictability, at 12:35 p.m. we captured an unbanded adult male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, followed by an immature male at 12:50 p.m. The latter bird had no red gorget feathers at all and the streaking on his throat was so light we actually thought he was female when we first caught him. His gender was confirmed when we examined the #6 primary; it male RTHU this feather is heavily tapered and sharply pointed at the tip (see file photo above). In female RTHU this feather is untapered and has a more rounded tip.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Counting the one we mist netted in Plot 4 earlier that morning that gave us three Ruby-throated Hummingbirds banded on our first day. It's worth noting that none of these three birds exhibited any signs of wing feather molt, something that usually starts as early as mid-November when RTHU are in the Neotropics. What was really fulfilling, however, was that at 12:45 p.m. we also trapped a fully gorgetted RTHU already bearing a band (above), #C52224--likely the bird Juan Diego had photographed the day before. That sent us straight to our data sheets, where we learned we had banded him as an immature male with partial red gorget on 13 November 2012, making him now a second-year bird. Amazingly, we caught him last year at El Cas in a Dawkins trap hanging from exactly the same hook! This particular hummingbird was important for one main reason: Although we banded a RTHU at El Cas on a scouting trip in February 2012 and retrapped it there with a group in November 2012, our newest recapture was the first time we had a Ruby-throated Hummingbird return to eastern Costa Rica in a later calendar year. This again confirms Ujarrás as the fourth Central American locale where we have found winter site fidelity for RTHU--the others being Crooked Tree at Belize and two sites ten miles apart in Guanacaste Province in western Costa Rica. Such a return is always exciting news because Operation RubyThroat researchers were the first--and still only--to document site fidelity for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds within the species' non-breeding range in the Neotropics.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With full bellies and much satisfaction over capturing three new ruby-throats and one previous-year return, the group bid a temporary goodbye to El Cas and headed via bus for nearby Cartago where we had scheduled an afternoon trip to Lankester Botanical Garden. Begun in the 1940s and donated to the University of Costa Rica in 1973, the research facility's claim to fame is a comprehensive collection of tropical orchids and other epiphytes. The garden is open to the public but doesn't look like a conventional conservatory because orchids aren't artistically displayed but are arranged scientifically along a series of long tables, depicting their tremendous diversity. Some orchids like the one-inch-wide unnamed yellow specimen above are relatively large and showy, but some such as the three just below are astounding because of their barely macroscopic blossoms.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The flowers of Specklinia tribuloides (above), resemble lobster claws but are only a quarter-inch in length. When pollinated the orchid's flower disappears and produces a seed pod that turns a dark blue-green at maturity. These little orchids from elsewhere in Costa Rica may have very specific insect pollinators that don't inhabit Lankester Garden, so its unlikely the plants will yield fruit "in captivity."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another tiny orchid, Lepanthes falx-bellico (above), was not discovered in Puntarenas, Costa Rica until 2003, indicating there is much to be learned about orchid flora. In fact, in the past decade or so Lankester Garden representatives have discovered at least 16 species of Lepanthes alone. (NOTE: The plant in the photo is the "holotype," i.e., the original specimen used to define and name its species.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A third miniature was another Lepanthes (above) that differed from its relatives in having translucent petals. Although we don't normally choose favorites when we're talking about nature, we couldn't help but be enchanted by this quarter-inch orchid marvel.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One last orchid that caught our attention was a dwarf species of Epidendrum, about a half-inch across. Because the flowers were a pale translucent green that blended with foliage, this plant almost certainly uses a fragrant nectar to attract potential pollinators.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From Lankester Garden we returned to Tapanti Lodge for a sumptuous buffet supper, followed by our usual instructional session during which we examined some aspect of hummingbird natural history, reviewed the day's accomplishments, and laid out plans for the morrow. (At Jim Shuman's behest, the group did a wild, 60-second recap of the previous day's events, thus bringing late-arriving Judy Schwarzmeier up to speed.) Every evening we also had presentations from a couple or three participants, each of whom regaled us with interesting info about their lives and nature-related experiences back home.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY THREE: The Adventure Continues • We got an earlier start on banding on 8 November because all our nets were already strung on poles and the group was considerably more efficient at erecting them among the arbors at Plot 4. Nonetheless, it was a long morning during which we caught zero Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, something that hasn't happened often on our Neotropical study sites. The hummers simply weren't visiting Chayote blossoms as frequently as in years past. Observations from various vantage points around the vast plantation indicated one difference between 2013 and our previous two Novembers at Ujarrás was that this year we observed a much earlier bloom of nectar-rich flowering trees including species of Erythrina (above) and Albizia. This may have been all well and good for the hummers, but it meant the birds were feeding high in the canopy instead of on ground-level Chayote flowers where we could capture them in mist nets.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite striking out on ruby-throats we did manage to mist net a few others birds. Take Tennessee Warblers, for example. On the preceding day we processed just one, but in less than five hours on 8 November we banded 23 TEWA and released numerous others when the banding table couldn't keep up with the influx. The high points of our day turned out to be encounters with more returning birds we first encountered locally in previous years. Initially impressive was a Northern Waterthrush we banded (#1561-13082) on 19 November 2011 (again scribed by Nancy Meier), recaptured on 15 November 2012, and caught again in 2013--all three events in Plot 4. This became our first Ujarrás bird to show site fidelity three years running. Amazingly, an hour later we netted Tennessee Warbler #2090-30090 that ALSO had been caught in Plot 4 (ever-present Nancy Meier scribing) on those very same days as the NOWA in 2011 and 2012; this offered further confirmation these long-distance migrants DO return to precisely the same locales each winter. Almost as an afterthought the group later that morning had TWO MORE Tennessee Warbler returns: #2090-30066 (scribed by Brenda Piper) from 18 November 2011 and #2090-30893 from 17 November 2012 (Gail Walder scribing).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On 8 November we caught another of those little Scintillant Hummingbirds, this time one with a broken row of iridescent feathers on the lower margin of its gorget (above). Unlike yesterday's female Scintillant, this individual had a throat pattern more like what would be expected in an immature male. Selasphorus hummingbird.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sure enough, when we looked at the lead primary feather (above), we found it to be heavily tapered--a definite sign of the bird's maleness. Clean, shiny, unworn flight feathers on this Scintillant Hummingbird were another sign of an immature individual.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center This particular hummer was released by Sharon Groves (above), who accompanied Phil Seward on our expedition and coyly referred to herself as an "incidental birder." Despite this self-bestowed categorization, Sharon--like all her fellow participants--was involved, interested, and productive. We suspect she also had a good time and learned a lot. With the morning's capture of two new unbandable resident hummingbirds--Blue-throated Goldentail and Green-breasted Mango, our 2013 list of hummers grew to six species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After shutting down our mist nets and having lunch at El Cas we re-boarded Alvaro's sleek and shiny bus to drive out of Orosi Valley, through Paraíso and Cartago, and up the long, winding road to Irazú Volcano National Park. Unfortunately, the mountaintop at 11,260 feet was heavily shrouded in clouds that periodically produced light rain--certainly not optimal conditions for observing birds or landscape.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Even so, we got good views of hard-to-find Volcano Hummingbirds and Volcano Juncos, and were able to photograph the more common Rufous-collared Sparrow, Zonotrichia capensis (above), perched on the giant leaf of Poor Man's Umbrella. You might notice similarities between this species and White-throated and White-crowned Sparrows of North America; they are indeed in the same genus.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Perhaps our favorite sighting of the afternoon was a flock of Sooty Thrushes (AKA Sooty Robins) with blue irises and orange bills and feet. These colors contrasted with the birds' slate-gray plumage that itself blended perfectly with the drab color of surrounding ash and lava flows. We also got some brief glimpses through the fog of Irazú's green-water crater before starting back down toward Tapanti Lodge.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After supper, we announced at the end of the evening meeting a list of nominations submitted as possible nicknames for this year's group. Some were mysterious, others misleading, but one in particular stood out. Henceforth and forevermore the Operation RubyThroat team that came to work in the Chayote fields in 2013 will be known as the "Ujarráscals"--a name that perfectly suited the group's collective personality while in Ujarrás.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY FOUR: The Adventure Continues • After getting skunked on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds during our second day in Plot 4, we decided to move operations to an adjoining plot where Ernesto, Diego, and Juan Diego had observed nectaring activity from a viewing spot atop a four-foot-tall volcanic boulder. This geological formation led to our calling the new research site "The Rock." This plot (above) was mostly level, with a wide drainage ditch running beneath an arbor that wasn't too dense to allow mist net deployment.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Ujarráscals got their nets up in short order and immediately started bringing in the Tennessee Warblers--a total of 50 by day's end! They also netted another Northern Waterthrush and a nondescript little brown bird that initially proved difficult for the group to identify--an immature female Indigo Bunting (file photo above). Regretfully, our move to "The Rock" yielded zero Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--our second consecutive day of getting shut out on banding our study species. Ouch!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We did manage to pull in a few unbandable resident birds on 9 November that wowed the group, including a Passerini's Tanager (above). The adult male in this eye-popping species has jet black plumage contrasting with a brilliant scarlet rump that undoubtedly serves in species recognition and mate selection for the female.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In closer view the male Passerini's has a ruby red iris and a bill in striking two-toned hues of blue and black. Many Central American tanagers have bright colors that help them stand out in the deep shade of the tropical forest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another resident bird that hit our nets on 9 November was an adult male Yellow-faced Grassquit (above). The bill shape suggests grassquits ought to be in the same family as as the American sparrows (Emberizidae), but DNA studies show they are actually "tholospizan finches" in the Tanager Family (Thraupidae). As such, they are closely related to the finches Darwin studied on the Galapagos Islands. Incidentally, female Yellow-faced Grassquits are much paler overall and have just a hint of yellow on the throat.

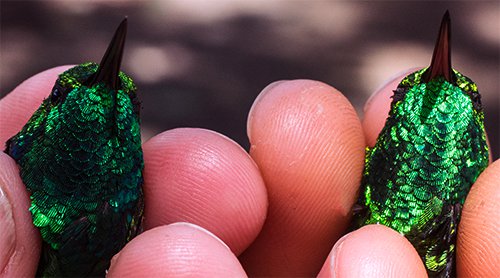

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And speaking of evolution, mid-morning on 9 November we had the unusual opportunity to capture two male hummingbirds that at first glance looked just alike. In actuality, they were two distinct species. Older Costa Rican field guides list a single species called Fork-tailed Emerald, Chlorostilbon caniveti, but recent field studies show there are actually two geographically separate congeners: Garden Emerald, C. assimilis (above left), and Canivet's Emerald, C. caniveti.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In addition to inhabiting different parts of Central America, upon close examination the two species have one significant morphological difference. Garden Emerald (above), endemic to western Panama and Costa Rica's Pacific lowlands around Guanacaste, has a lower mandible that is completely black.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In contrast, the lower mandible of Canivet's Emerald is orange-red (above). This bird has a much wider distribution than Garden Emerald, occurring from Mexico through western Nicaragua. Within Costa Rica, however, its northwesterly breeding range in Guanacaste is geographically separate from that of Garden Emerald, allowing for allopatric speciation. This Canivet's Emerald we caught at Ujarrás was "out of range" and allowed unusual opportunity for the group to compare it with the locally common Garden Emerald. In addition to the two emeralds we also captured a Violet Sabrewing male that brought our 2013 hummer count to nine species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After striking out on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds on 9 November we shut down banding operations at "The Rock," enjoyed lunch at El Cas, and then headed up the Orosi Valley toward Tapanti National Park. Along the way we saw a giant Erythrina tree (above), festooned with Spanish moss and nearly countless bromeliads. The crowning touch was an adult Roadside Hawk perched on topmost branch. Although this species is similar to North America buteos and was once grouped with them, it's now the monotypical Rupornis magnirostris, i.e., the only species in its genus. Up to a dozen subspecies occur from Mexico to Argentinian grasslands. Only about 12"-16" long, Roadside Hawks prey on everything from lizards and mice to small monkeys.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We've never been to Tapanti National Park when it wasn't raining, and this year's trip was no exception. That, we suppose, is to be expected when at an altitude of up to 8,000 feet in a tropical rain forest. Tapanti is the perhaps the rainiest place in all of Costa Rica, with as much as 300 inches of rain annually; that's 25 feet! The group was able to make a few habitat observations after bundling up in rain gear; true-to-form, resident tico Ernesto (above, through the windshield) simply got wet and changed his shirt after re-boarding the bus. Continuous precipitation prevented us from breaking out expensive camera equipment so we have no good photographic record of the field trip. Worse yet, we didn't see any water-ouzels (AKA American Dippers)--an anticipated highlight when one goes to Tapanti. • DAY FIVE: The Adventure Continues • We got dried out from the soggy Tapanti field trip in time for our traditional mid-week "Hump Day" on 10 November, set aside so our team could take a break and visit more distant sites than would be accessible during just the afternoon hours. The group slept in a little later, took breakfast at the Lodge, and then drove about two hours east to one of Central America's top birding spots: Rancho Naturalista. The Rancho, where 'Nesto once worked as resident naturalist, was established about 25 years ago and is a must-visit locale when in Costa Rica.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rancho's current staff members maintain a variety of water features and bird feeders--some baited with bananas and other fruit, and the rest with sugar water. The latter attract hummingbirds, while the former attract just about any other bird imaginable. All this provides a three-ring birding circus easily viewable from a second story veranda (above) overlooking the feeding area and surrounding forest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One favorite of the Ujarráscals was a Collared Aracari (above) that came in to gobble bananas with its massive bill. This colorful bird is about 16" long, at least a fourth of which is mandibles.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As might be expected, aracaris are related to toucans (Ramphastidae); what many folks don't know is that toucans are actually in the Piciformes, the bird order than includes woodpeckers. We find it interesting that Collared Aracaris are social roosters, with several adults and recently fledged young sharing the same cavity.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Aracaris seldom excavate their own nest hole but take advantage of one excavated and abandoned by their woodpecker relatives--perhaps a Black-cheeked Woodpecker (male, above). This particular picid is found throughout the Western Hemisphere's equatorial belt from southern Mexico to western Ecuador. One of the "ladder-back woodpeckers," it resembles the Red-bellied Woodpecker of North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Having captured and examined the brilliant red and black male Passerini's Tanager on our study site among the Chayote, the Ujarráscals were surprised to see the relatively drab plumage of sexually monomorphic Palm Tanagers (above). As suggested by its name, this species typically nest in palm trees, but it's not uncommon to find a pair building under the eaves of a house.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rancho Naturalista's banana feeders do indeed attract a diversity of birds, but our group was naturally drawn to numerous sugar water feeders that hang from the second-floor veranda at the main lodge. The show put on by at least a dozen hummingbird species is unforgettable, and it's almost impossible to capture the non-stop activity without a video camera. Even so, stationary birds provide ample opportunities for close-up still photos, sometime even with a standard 50mm lens as the hummers fly right up to one's nose. One group favorite was the White-necked Jacobins (above). The adult male of this species has a very formal appearance with azure blue head and neck; emerald green wings, back, and shoulders; and a pure white belly and tail. (A prominent white spot on the nape gives the bird part of its common epithet "Jacobin" apparently comes from the name of a hyperactive political group during the French Revolution.) This species--nearly twice the size of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird--is harder to see in the wild because it hangs out in the canopy.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The female White-necked Jacobin (above), highly variable in plumage, looks nothing like her potential mate. Heavy scalloping on the breast is a good indicator for the female. The species occurs from Mexico to Brazil, with a disjunct population on Tobago.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Before lunch at Rancho Naturalista we also had time to navigate a short trail into the woods, where staff members maintain a couple of hummingbird feeders away from the hustle and bustle of the lodge building itself. There we found some shyer hummingbird species, including an adult male Green-crowned Brilliant (above). This is another large-ish hummer about the same size as the five-inch-long White-necked Jacobin.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Lunch on the porch at Rancho was splendid, as always, and shortly thereafter most members of the group got to see one of the lodge's signature species: A male white-crowned Snowcap hummingbird that was moving 'way too fast for photos. With that bird added to the checklist we drove back eastward, stopping at CATIE--short for Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. This international organization is devoted to research and education related to tropical agriculture--and especially in ways local farmers can be self-sustaining. The Center has had joint projects with more than 200 partner institutions around the world, particularly Latin America. Although the Ujarráscals did get to tour the facility and examine samples of all sorts of tropical fruits (above), rain once again interfered with suitable photographic documentation--hence, few photos.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY SIX: The Adventure Continues • Following our "Hump Day" excursion the team returned once again to the Chayote fields, with dawn revealing the best sunrise (above) of the entire week. We enjoy colorful sunrises, but keeping in mind the old phrase "Sunrise in morning, sailors take warning" we were concerned more precipitation would slow down field work--which, in fact, it did. A few light showers throughout the morning seemed to impede bird activity and, once gain, we caught zero Ruby-throated Hummingbirds at "The Rock," making this three field days in a row of no RTHU netted among the Chayote.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Thanks to the persistence of Kathy B. (above), we did manage to begin repairing four mist nets that somehow had come to Costa Rica with broken shelf strings. What nets we did deploy--ten of them--managed to capture a couple of adult male Indigo Buntings in their typical midwinter calico plumage (photo at right, courtesy Jenine Pontillo), and we netted a brightly colored adult male Baltimore Oriole whose colors shined even under overcast skies. Lest we forget, we also banded our daily allotment of 29 Tennessee Warblers, which we're beginning to think must be the most common of all members of the Parulidae.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One unbandable resident species that caught the eyes of the Ujarráscals was a Buff-throated Saltator (above); the bird's bill power likewise managed to impress a few participants who extended their fingers to determine how strong it could bite. Although saltators were once thought to belong in the Cardinalidae, taxonomists have moved them in with the tanagers (Thraupidae)--a group group that seems to be growing bigger each year due to DNA studies. Despite their powerful chomping ability, Buff-throated Saltators feed mostly on tree buds, fruit, nectar, and relatively sedentary insects such as beetles. We suspect the bird in the photo is an immature; a full adult would have a darker black bib and more defined facial plumage.

Arguably the most exciting capture of the day for the Ujarráscals was a local bird they'd seen on banana feeders at Rancho Naturalista. We speak here of the Blue-crowned Motmot (file photo above), whose riotous colors and heavily serrated bill were a sight to behold. Curiously, motmots are cavity nesters in embankments--hence the mud caked on the bird's mandibles.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We fully understand that when few birds are captured the day gets long for participants. Even so, everyone--including Judy Schwarzmeier and Gary Wolf (above)--worked diligently, conscientiously, with excitement, and without complaint, Even so, they were always happy to make the long walk back to the banding table for "show-and-tell."

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On our fourth morning in the field Ernesto learned from talking with local farm workers that 2013 had been an especially bad year for snail infestations. (Identification of the snail is unknown, possibly a Simpulopsis species in the Bulimulidae. If you're into malacology and have a suggested I.D. please send a note to INFO.) Tiny snails--the one in the photo above had a shell only about a quarter-inch-long--slide into crevices in the Chayote itself, rasp its contents, and make the fruit unsuitable for sale. One supervisor told 'Nesto there was no safe chemical treatment for the pests and that he was spending $10,000 PER WEEK to pay laborers to pick off the snails by hand.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although it never rained heavily on 11 November, the Ujarráscals were damp enough to look forward to drying off at lunch, so we shut down a tad early and went to El Cas for another tasty meal. As usual, we opened our four portable Dawkins traps and at 12:50 p.m. finally caught an immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Excited by the potential, the group hung around for another hour without trapping anything, so we sent them off on a walking tour of the old church ruins that make Ujarrás a popular tourist spot for Costa Ricans and foreign nationals alike. (That's Leslie Bergum in the photo above, apparently giving some sort of secret sign.) Ela and trip leader Hilton optimistically stayed behind to watch the traps, but by 4 p.m. when the team returned from sightseeing no other RTHU had been caught. In any case, the one ruby-throat we did trap earlier brought the 2013 total to four--three of which had been trapped at El Cas and NOT mist netted in the field. Like mentioned earlier, it appeared an early bloom of neighboring tree flowers was a bigger draw than the Chayote, but perhaps sugar water in feeders was just too rich an opportunity for at least those few hummers that ventured into our traps.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On the way back from El Cas to Tapanti Lodge we had our best view of a reptile during the week: An old male Green Iguana, Iguana iguana (above), "sunning" in tall canes along the roadside. Despite its ferocious appearance, the arboreal Green Iguana is primarily herbivorous on leafy matter, tender new plant growth, and fruit--a hard-to-digest diet that leads iguanas to sit motionless for long periods of time. Females are less heavily armored than males and lack the big throat dewlap that indicates mature masculinity.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY SEVEN: The Adventure Continues • Our fifth day in the field had its share of surprises. Considering the paucity of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in Plot 4 and at "The Rock," we had decided to move operations to a nearby field, but when we arrived at our usual Chayote farm after breakfast we found all the gates locked. Apparently the laborers were working elsewhere and had no reason to unlock them. Fortunately, Chayote agriculture is widespread in the area around Ujarrás, so we stayed on the bus and drove elsewhere. Our eventual destination was a sparsely vegetated year-old plot about a mile eastward near the settlement of San Juan, known disparagingly by the locals as "Little Hell." As the Ujarráscals waited on the white bus (visible at the far northern end of the road in the photo above), the trip leaders walked in and scouted for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. As we reached the terminus we did find more ruby-throats feeding on Chayote than we had seen on our previous plots, so we waved the driver into what would become a new study site. Locked gates forcing a move to "Little Hell" turned out to be the best thing that could have happened. The photo above faces north with Irazú Volcano hidden by clouds. Behind us was a wall of tall trees and a slope leading toward Lake Cachi, which we could see through the vegetation.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Chayote growth at our new site was sparse, allowing relatively easy net deployment by Mary Siebel (above) and others, but it was nectar-productive and there were plenty of birds around. Our first captures were a new species for the week--a couple of adult male Yellow Warblers caught before all the nets were up at 8:15 a.m.; a female YEWA followed 15 minutes later and we caught one more adult male at noon.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The hard part about working in Little Hell was on-and-off showers throughout the morning. We were catching birds and moving them quickly into lingerie bags, but precipitation made it impossible to keep the banding table dry. (We should have brought a tarp!) At mid-morning Ernesto and Ela volunteered to close the nets while the team got back in the bus (above) and made the short drive back to the friendly confines El Cas where we could work under cover.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Although Andrea hadn't expected us at El Cas quite yet, she got a big pot of coffee going and warmed up the Ujarráscals while we banded the birds we'd brought with us (above). Andrea (with her back to us in the photo) was more than a little pleased to see all this research activity unfolding at her restaurant.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The morning's bandings included a male Mourning Warbler, a Northern Waterthrush, a female Indigo Bunting, and adult male Baltimore Oriole, and an immature male Rose-breasted Grosbeak (the latter being photographed above by Kathy B.). Better yet, we also had one immature male Ruby-throated Hummingbird in the mix from Little Hell; we banded him first while at El Cas and allowed him to drink as much sugar water as he wanted.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Altogether that rainy morning we also banded 13 more Tennessee Warblers, one of which the scribesmaid accidentally released at El Cas. (As you continue reading, don't forget our mentioning this bird!) All the rest--including the ruby-throat--we took back via bus to Little Hell and let them go where we'd caught them. Although chilly from the rain, Ernesto and Ela were waiting patiently for our return, so we re-opened nets and went back to work. Among first captures was a male Tropical Parula (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike most of its relatives in the Wood Warbler family--this species is not a Neotropical migrant. It resembles the Northern Parula, its close relative, but lacks a broken white eye ring; Tropical Parulas also have no blue and russet breast band found in adult male NOPA. (That said, some authorities lump the two parulas as one species.) Tropical Parulas do breed occasionally in very southern Texas, as well as Mexico, all of Central America, and as far south as northern Argentina.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another unbandable resident species we captured at Little Hell was Prevost's Ground Sparrow, Melozone biarcuatum, AKA White-faced Ground Sparrow. This colorful emberizid species occurs from southern Mexico to Costa Rica, but the local population (above) looks a bit different from those that occur in other parts of the breeding range, with considerably more facial marking. (We'd be hard-pressed to say the bird above was white-faced. Note also the raindrops on the bird's back.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Within Costa Rica, Prevost's Ground Sparrows occur only in the Central Valley and are completely isolated from their nearest relatives elsewhere in Central America, leading some ornithologists to consider them a separate species: Cabanis's Ground Sparrow, M. cabanisi.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In between showers we mist netted three other hummingbird species at Little Hell. The first was a Stripe-throated Hermit (above), formerly known as Little Hermit. This smallish brown hummer with a decurved bill forages for nectar near ground level across Central America and into northwestern South America. Sexes are identical in appearance. The second hummer was a male Green Thorntail that unfortunately slipped from our grasp during show-and-tell and for which the group got only hurry-up photos; the image above right (courtesy Jim Shuman) still manages to show the bird's dark green body, short bill, and unusually long tail. Females lack these long rectrices and have prominent white mustaches. Within Costa Rica this uncommon species is found only on the Caribbean Slope.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As rain continued we thought several times about just shutting down for the day, but human skin is waterproof and the Ujarráscals had come a long way to do field work. Since there was no torrential downpour and we could keep the birds dry and warm, everyone agreed we should just keep plodding on. This attitude paid off royally near the end of the morning when we caught another new hummingbird--arguably one of the most spectacular hummers in all of Costa Rica: Black-crested Coquette (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The adult male Black-crested Coquette is a bird that appears to have been put together by a committee: Long, hair-like crest feathers; pink lower mandible, intensely iridescent green face; a scattering of metallic gold belly plumage; and long black gorget feathers that flare out during mating displays. (Despite wisecracks from the Ujarráscals, our photo does NOT reveal this bird has a #2 pencil in place of a bill.) We saved this bird for our penultimate show-and-tell, which we conducted after everyone except Jim Shuman boarded the bus.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After we unveiled the coquette to the Ujarráscals we transferred it to Ernesto, who has always wanted to have this species in-hand for close examination. 'Nesto let the bird perch on his finger (above) and stuck his hand out the door of the bus, where Jim Shuman and his umbrella allowed us to use our camera take an unforgettable photo. The Green Thorntail and Black-crested Coquette brought our list of hummingbirds caught and handled at Ujarrás to 12 for 2013 and 16 since 2011--both impressive numbers when we remember only 51 species occur in all of Costa Rica. Although the coquette was an amazing capture, we still had one final bird to show the group--an immature ruby-throat that was our first female of the trip. This last-minute capture at 12:30 p.m. as we closed the nets brought our 2013 RTHU total to six.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Soggy once again, the Ujarráscals were pleased to drive around Lake Cachi to La Casona del Cafetal, a working coffee plantation that has a elegant outdoor restaurant (above). We always enjoy visiting the Casona, in part because that's where trip leader Hilton and wife Susan were privileged to be part of the wedding of Ernesto and Ela back in 2009.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The Casona's dining patio offers a million-dollar view of Lake Cachi (above), framed by a lush assortment of native and ornamental plants. This lake is formed by a tall dam used for hydroelectric power and is a favorite birding spot for folks wanting to add waterfowl species to their in-country lists.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the most noticeable plants on the lake is Common Water Hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes (above), a native of the Amazon Basin that has become an invasive aquatic species around the world. The plant was introduced as an ornamental--its pale purple flowers are indeed pleasing to the eye--but it grows so prolifically it clogs waterways and chokes out native species. Attempts at biological control have used weevils and plant hoppers, with limited success. One good thing about Water Hyacinth: It's a floating plant with lots of rootlets that trail in the water beneath and absorb contaminants such as phosphates, mercury, and lead.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not far from the shores of Lake Cachi is a large tree with an interesting structure (above) protruding from its base. We found this white object three years ago on our first trip to the area and always take time to check on its status. When we asked the Ujarráscals to guess what it was, a few solved the puzzle: It's a waxy tube created by a hive of stingless bees that live inside the tree's hollow trunk. This colony has been going strong for at least three years. It boggles the mind to think how many eggs must have been laid over that time span as the queen continued to replenish her hive's complement of worker bees.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we prepared to depart from the Casona there was a break in low-hanging clouds (above). This allowed us a brief look at far-off Irazú Volcano and some of the communications towers along its summit.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On the way back to Tapanti Lodge we dallied at a roadside woodcarver's shop to view the work of a local craftsman. This gentleman uses wood from old coffee plants that are removed as they become too old to produce. His items, although primitive, are always a nice keepsake from Costa Rica. (The Hiltons, above, selected a couple of items to add to their granddaughters' nativity scene that is populated by carvings from this shop. Don't tell the girls, though; it's a Christmas surprise.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On final stop on the way back to Tapanti Lodge was at one of the lookouts that provided a panoramic view of the Orosi Valley. In the photo above, the seemingly smooth pale green areas are the Chayote arbors where we ran mist nets during the expedition. Further back is Lake Cachi, most of whose surface is covered by masses of that floating Water Hyacinth. • DAY EIGHT: The Adventure Continues • The Ujarráscals returned to Little Hell on our sixth and final day with mixed feelings. Everyone was thinking about going home, but the team was even more eager to see if we could catch some more hummingbirds. The weather, at least, was a bit drier--although we still had light drizzle at various times during the morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We knew we'd have a good day when the first bird in a net at 7:10 a.m. was an adult male Prothonotary Warbler (above right) with bright golden plumage; we actually caught a second one just a few minutes later and got to compare their similarities and differences.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another parulid wandered into a net at 7:40 a.m.--this time an immature female Golden-winged Warbler (above). This Neotropical migrant is one of our favorites, in part because we're intrigued and concern about its precipitous decline across its breeding range in south-central Canada, New England, and the Appalachians where it must compete with the closely related Blue-winged Warbler. We seldom see this species in South Carolina at Hilton Pond Center; there we've banded only four since 1982.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Later that morning we caught another Yellow Warbler (an immature male) and a new migratory species: Yellow-bellied Flycatcher (above). We also pulled in 48 more Tennessee Warblers, bringing our six-day total to a whopping 164. Surely one of those TEWA will be encountered sooner or later back in North America! Of even greater interest were two other TEWA netted on our final day. One of them was the bird we had accidentally released after banding the day before--a mile away at El Cas--and a good example of short-distance site fidelity. The other (#2090-30872) had been banded last year on 16 November in Plot 4 (scribed by Ann Truesdale). This bird was still demonstrating long-distance site fidelity, even if it was recaptured in Little Hell about a mile east of its banding locale. When you consider this bird had spent the breeding season at least 2,000 miles to the north, being caught one mile away in a subsequent year isn't all that far.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The really good news on 13 November was it ended up (finally!) as our best day for catching Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. In fact, it was a terrific morning, four adult males, three immature males, and two females (file photo above of a color marked individual). Those ten RTHU brought the Ujarráscals total to 15, which was a respectable total that equalled the 15 we banded during our first expedition at Guanacaste back in 2004 and again during our initial trip to Nicaragua in February 2013. As noon approached the rains picked up, slacked off, and started again, so we decided to call an end to 2013 field work in the Chayote fields. The Ujarráscals trudged in with nets and poles, 'Nesto moved the soggy mist nets into plastic bags for eventual transport back to Hilton Pond Center, and Alvaro aimed his bus out of Little Hell toward Finca Cristina at Paraíso (which is the Spanish word for Paradise). It's not often one gets to experience Hell and Paradise all in one day.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At the finca 'Nesto's mom Linda had prepared a sumptuous lunch that included a few dishes made from--what else?--Chayote. Linda (standing at center, above) also related tales of how she and Ernie, just-retired from the U.S. Navy about 30 years ago, came to start a coffee farm in Costa Rica.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After the meal 'Nesto took the group on a walking tour of the finca property, where he explained the natural history of coffee and talked extensively about the intricacies of biological control and organic, shade-grown coffee farming. If you've ever been to a sun-grown coffee farm, you can appreciate from the photo above how different the finca's philosophy of coffee-growing really is.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the big differences between sun-grown coffee megafarms and Finca Cristina's environmentally sensitive growing techniques is the big producers use tons of herbicides and pesticides and fertilizers. The finca actually encourages a natural balance that includes growth of native plants such as Shrub Lantana (above), whose fruits attract birds that just might glean pesky insects from adjoining coffee trees. What an enlightened way to farm--especially since Lantana is a documented winter food source for those Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in which we are so interested!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Later in the afternoon, Papa Ernie (above right) regaled the group with explanations of his self-styled assortment of original but very efficient coffee-processing devices. As Ernie can attest, necessity is indeed the mother of invention.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eventually folks made their way back to Finca Cristina's roasting room, where Linda and 'Nesto showed how coffee is prepared for consumption and shipping. Multi-talented Ela (above)--who had been so helpful with mist net extractions in the field--was on hand to help with bagging either whole beans or ground coffee the Ujarráscals purchased to take up any empty luggage space on their return flights. Some even promised to order more from the Café Cristina Web site.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY NINE: The Adventure Never Ends • As might be expected, our final day in Costa Rica dawned with our clearest skies yet. We could have used a little less precipitation in what turned out to be our wettest expedition ever the Neotropics, but we were glad the weather looked good for flights back to the U.S. We were also pleased the Ujarráscals finally got a good look from the Lodge balcony of Turrialba Volcano on the horizon (above). We'd been telling them every morning to look for the vapor plume from this distant peak, but they were beginning to doubt its existence.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After our final breakfast folks checked out and moved their bags toward the bus. Even as the group was about to depart, we couldn't resist one last teaching opportunity by pointing out a couple of social wasp nests (above) in the rafters over our heads. Most of the time it had been too dark for a good view of these amazingly abstract structures, but in morning light they looked like something one would find at an art festival.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The group gathered one last time at parking lot of Tapanti Media Lodge to say goodbye to Ernesto. To avoid an unnecessary trip to and from the airport, he stayed behind as the Hiltons and the rest of the Ujarráscals boarded Alvaro's bus and went back east through Paraíso, Cartago, San José, and Alajuela before arriving at the airport. En route, Mary Wolf--official compiler of the bird list--read out names of all species we had seen and/or heard; collectively the group had one of the highest totals of all our 22 Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Central American with an impressive 127 species.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not everyone was actually going to the San José airport; a few folks were spending an extra night to get better connections or going on extended trips around Costa Rica. In any case, every time we dropped someone off at an area hotel it was another opportunity for farewell hugs, and we further extended goodbyes at the airport when just two outgoing flights were transporting eight of the Ujarráscals--allowing even more talk-time in airport waiting areas.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Eventually, like all good things our time in Costa Rica came to an end and our citizen scientists dispersed to destinations from New Hampshire to Wisconsin and south to the Carolinas. The Ujarráscals were a terrific, inquisitive, rascally group that did excellent field work under sometimes trying circumstances including unpredictable Neotropical weather. We're happy to have reunited with some old acquaintances among the Chayote in Ujarrás and to have made a bunch of new friends, too; we're hopeful each 2013 participant will become an Operation RubyThroat "groupie" and join us for other expeditions in 2014--and for years thereafter. In closing, we say to the Ujarráscals a phrase they'll find familiar: "We're glad you were there." All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center POSTSCRIPT: Wife Susan and I returned from Costa Rica on 14 November and three days later I underwent surgery on my elbow to alleviate ulnar nerve damage that caused muscle atrophy in my right hand. I'm still recovering but look forward to re-commencing bird banding and other research and education initiatives at Hilton Pond Center over the next few weeks; I also hope once again to investigate reports of winter vagrant hummingbirds around the region. In the meantime, I beg your indulgence in being slow to produce this write-up about our recent trip to Ujarrás, presented here as a scientific account and as a labor of love so the Ujarráscals will have permanent record of their time in Costa Rica.

All text, maps & photos © Hilton Pond Center I'm not sure when the next installment of "This Week at Hilton Pond" will be posted, but I hope you enjoyed reading about the expedition just completed. Please note that a few slots are still available for the March 2014 Operation RubyThroat trip to Crooked Tree Sanctuary in Belize (giant Jabiru stork and other wading birds, above). There we'll have at least as much fun as the Ujarráscals experienced in Costa Rica. I'm sure by March I'll be healed enough to band birds among the Cashew trees at Crooked Tree, so please sign up today. Pura vida! BILL HILTON JR. All contributions are tax-deductible on your •UJARRÁS 2013 EXPEDITION RECAP• Our November 2013 Operation RubyThroat expedition to Ujarrás (in Costa Rica's Orosi Valley near Paraíso and just east of San José and Cartago) was a qualified success, as determined in part by results outlined below. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For complete reports on all of Operation RubyThroat's successful Neotropical Hummingbird Banding Expeditions, please visit

All contributions are tax-deductible on your |

|---|

|

"This Week at Hilton Pond" is written and photographed by Bill Hilton Jr., executive director of Hilton Pond Center for Piedmont Natural History

|

|

|

Please refer "This Week at Hilton Pond" to others by clicking on this button: |

Comments or questions about this week's installment? Send an E-mail to INFO. (Be sure to scroll down for a tally of birds banded/recaptured during the period, plus other nature notes.) |

We were met by Ernesto Carman Jr. (with Wood Duck, at left), our long-time friend and colleague and one of Central America's premier nature guides. We've known 'Nesto since that very first Operation RubyThroat trip to Guanacaste Province in western Costa Rica; in fact, it was HE who discovered a previously unreported population of RTHU in Aloe Vera plantation that became our first Neotropical study site almost ten years ago. Ever-vigilant for ruby-throats, 'Nesto more recently found another RTHU concentration in the Central Valley east of San José at the little farming community of Ujarrás (photo above), where extensive fields of nectar-laden Chayote flowers attract our target species. It was these agricultural fields that were the destination for our just-completed November 2013 expedition to Costa Rica, as detailed below.

We were met by Ernesto Carman Jr. (with Wood Duck, at left), our long-time friend and colleague and one of Central America's premier nature guides. We've known 'Nesto since that very first Operation RubyThroat trip to Guanacaste Province in western Costa Rica; in fact, it was HE who discovered a previously unreported population of RTHU in Aloe Vera plantation that became our first Neotropical study site almost ten years ago. Ever-vigilant for ruby-throats, 'Nesto more recently found another RTHU concentration in the Central Valley east of San José at the little farming community of Ujarrás (photo above), where extensive fields of nectar-laden Chayote flowers attract our target species. It was these agricultural fields that were the destination for our just-completed November 2013 expedition to Costa Rica, as detailed below. The property, purchased about 30 years ago by Ernie Sr. and Linda Moyher

The property, purchased about 30 years ago by Ernie Sr. and Linda Moyher

Next morning we were up bright and early at the

Next morning we were up bright and early at the

These were unusable in the field until indefatigable Kathy over the next three field days worked to re-string them--a task made more difficult by wind and occasional showers.

These were unusable in the field until indefatigable Kathy over the next three field days worked to re-string them--a task made more difficult by wind and occasional showers.

This is another hummingbird species for which taxonomy is up in the air, so don't be surprised by future lumping or splitting.

This is another hummingbird species for which taxonomy is up in the air, so don't be surprised by future lumping or splitting.

As always, we simply could not have undertaken our work without the efforts and good nature of in-country guide and research colleague Ernesto Carman Jr.

As always, we simply could not have undertaken our work without the efforts and good nature of in-country guide and research colleague Ernesto Carman Jr.

the 14-member "Ujarráscals" team (plus leaders) helped catch, band, and release unharmed

the 14-member "Ujarráscals" team (plus leaders) helped catch, band, and release unharmed  six were adult males with full red gorgets, and only three were females

six were adult males with full red gorgets, and only three were females  This re-trap at the outdoor restaurant of a known second-year male with full red gorget

This re-trap at the outdoor restaurant of a known second-year male with full red gorget  old plumage that must be replaced before the long migratory flight back north. This contrasts greatly with RTHU captured in western Costa Rica in February when most birds have wing molt complete or well underway

old plumage that must be replaced before the long migratory flight back north. This contrasts greatly with RTHU captured in western Costa Rica in February when most birds have wing molt complete or well underway  the

the  This on-going project has focused primarily on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

This on-going project has focused primarily on Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

Oct 15 to Mar 15:

Oct 15 to Mar 15: