|

HOME: www.hiltonpond.org |

|||

THIS WEEK at HILTON POND Subscribe for free to our award-winning nature newsletter (Back to Preceding Week; on to Next Week) |

COSTA RICA EAST 2014: - PREFACE - When the last of this year's Ruby-throated Hummingbirds departed Hilton Pond Center in mid-October, my thoughts soon turned to following these tiny migrants to their non-breeding grounds far to the south. Each year since 2004 I've led citizen scientist groups--backyard birders, teachers, nature photographers, retired folks, college students, and other hummingbird enthusiasts--to ruby-throat hangouts in Central America, where I'm the only researcher conducting long-term studies on this species within its tropical wintering range. My colleague Ernesto M. Carman and I have worked with nearly 200 volunteers, some in his home country of Costa Rica, and in Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua--all countries where RTHU occur after departing North America each autumn. Our 23 excursions through Operation RubyThroat: The Hummingbird Project have focused primarily on banding and observing a common North American breeding species that has gone almost unstudied south of the border--even though ruby-throats spend half their lives there.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's worth noting that prior to my work only 46 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds had ever been banded in all of Mexico and Central America. By comparison, in the ten years since Operation RubyThroat research began in the Neotropics, my teams helped capture and band an astonishing 1,243 of these long-distance migrants and helped document RTHU behaviors and phenomena new to science. With these kinds of results I began planning a year ago for another November 2014 trip to Ujarrás, a tiny agricultural village in the Orosi Valley not far east of San Jose and just a few miles from Ernesto's hometown of Paraíso (see map above).

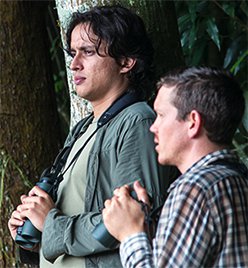

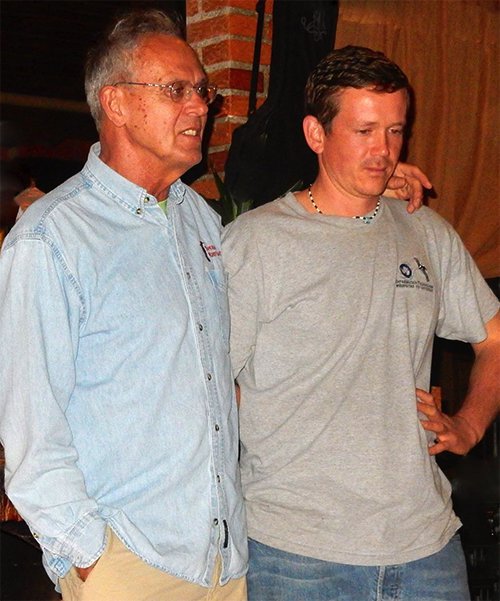

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In rich bottomland along the Rio Orosi, 'Nesto observed a concentration of wintering Ruby-throated Hummingbirds--drawn to prolific blooms of commercially grown Chayote squash, Sechium edule (note the nectar droplet in a flower, above). This RTHU population was far from previously documented wintering ruby-throats we'd studied in Aloe Vera plantations near Liberia on Costa Rica's Pacific Coast (see map) and was unknown prior to 'Nesto's remarkable discovery. After this earth-shaking find, in November 2011 we mounted our first "Costa Rica-East" expedition to Ujarrás and returned in 2012 and 2013. With all this in mind, early on 5 November 2014 I packed my bags at Hilton Pond Center, drove to Charlotte NC, and boarded a flight for San Jose, Costa Rica (via Atlanta)--a few days ahead of meeting my 24th group of Operation RubyThroat citizen scientists and the fourth team to conduct investigations among the Chayote. After clearing customs in San Jose I was met by Ernesto, but tagging along for the ride was old friend Juan Diego Vargas (at left in photo below right, with Ernesto)--

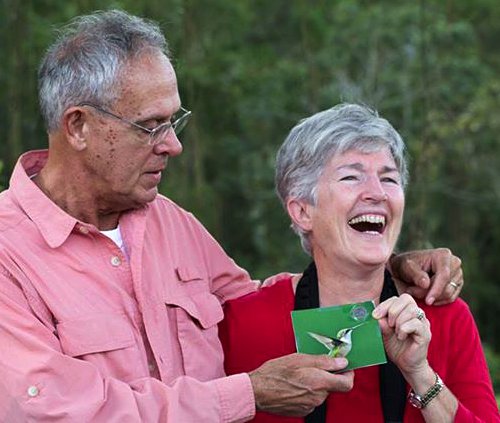

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After arriving at Finca Cristina and greeting the Carmans (below right), I followed my usual strategy of setting up my tripod and camera and focusing it on a banana feeder near the door of the main house.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center While watching the banana feeder I even managed to get a "lifer" in trees overhead, where my first-ever female Golden-olive Woodpecker, Colaptes rubiginosus (above), was foraging and bathing among wet leaves. This is another bird whose taxonomy has been in flux; formerly called Piculus rubiginosus, its new genus reflects a relationship closer to flickers rather than to several smaller tropical woodpeckers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another reward of observing the banana feeder was a twilight look at a couple of male Summer Tanagers (above) in full breeding plumage--a bird I knew well as a breeding species back home at Hilton Pond Center. After the sun went down the Carmans were kind enough to prepare supper--as they did the next few evenings--after which we sat around and chatted about hummingbirds, coffee growing, family, and the status of Turrialba Volcano. It was great to be back in Costa Rica. The summary report that follows documents the unprecedented scientific success of our just-completed Costa Rica-East Operation RubyThroat expedition to Ujarrás and is offered with affection and appreciation for the 11 hard-working citizen scientists who became such good friends during the nine-day expedition. This photo essay is a permanent record for the team, although I'm hopeful many Web site visitors will take vicarious pleasure from reading my account--and that you'll consider joining me for an upcoming hummingbird trip to the Neotropics in late 2015 or thereafter. (NOTE: Because I spent a LOT of time at the banding table this year I got to use my camera less than usual. Thus, I'm pleased trip participants offered some of their photos to round out the story. Their images are acknowledged where used.) BILL HILTON JR.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • PRE-ARRIVAL ACTIVITIES • We typically fly into Costa Rica few days ahead of the team to make sure our Operation RubyThroat research permit is in order with the ministry of the environment, to visit the Carmans at Finca Cristina, to scout the Chayote fields, and to help Ernesto prepare assorted field equipment he so graciously stores for us at the finca. This year we had another reason for early arrival: Turrialba Volvano--visible from our study site at Ujarrás--had erupted just a week earlier and we needed to know first-hand if fallout from its towering plume would impact our field work or participant travel. On our previous three annual trips to the Chayote fields we observed a small steam plume that began emanating from Turrialba back in 2001. Volcanic activities and small earthquakes increased thereafter, culminating in the recent major eruption early on 30 October 2014 (above); it yielded a towering cloud of black ash and white steam.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center That 30 October eruption lasted about a half-hour and was Turrialba's first big bang in 144 years. The event blew open a side crater (above) and the resulting ash caused immediate closure downwind at Irazú Volcano National Park--a site we hoped to visit with our team on an afternoon nature excursion. Despite the magnitude of the recent eruption Turrialba calmed down rapidly and by the time we got to Costa Rica a week later ash production had subsided and only a vapor plume was visible. When the team arrived on 8 November Turrialba offered a picturesque backdrop to our hummingbird field work and reminded us we were in a part of the world still quite new and geologically active.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Satisfied Turrialba posed no threat to our research or the well-being of our citizen scientists, the Omega Team (Hilton, Carman, and Vargas) headed out for Ujarrás on the morning of 6 November to scout Chayote fields for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. These fields are extensive, covering hundreds of acres divided by a grid-work of roads that cross every few hundred yards. We first visited a plot that had been very productive in 2011, only to find almost no Chayote flowers--likely because the vines had gotten old. A second plot bordering a mountain stream also showed fewer flowers. We spent the next couple of hours wandering dirt roads throughout the Chayote, stopping frequently to scan for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds; it was distressing to see only a handful of adult males feeding on scare blossoms and perching on the vines (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We did spot a few other resident bird species but only a smattering of migrants--including several Tennessee Warblers that typically are our most-commonly-banded passerines on our Neotropical trips. About the only truly bright spots around the older Chayote fields were Hanging Lobster Claws, Heliconia rostrata (above), growing in the hedgerows. This is the Heliconia species seen most commonly around lodges and developed areas; oddly enough, it is a non-native and Bolivia's national flower--imported from South America to Costa Rica as an ornamental. Click on photo for a full panoramic view in a new browser window All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our last stop was a Chayote field (above) near a tiny barrio where we worked for the first time last year. The site--nicknamed disdainfully by a neighboring town as "Little Hell"--yielded most of the 15 ruby-throats we banded in 2013, but this year's scouting trip indicated it was hosting almost no hummingbirds in early November 2014. By morning's end we were chagrined by a near-absence of RTHU--and of the other 27 hummer species we observed feeding on Chayote nectar in past years. This lack of target species did not predict success for our upcoming research expedition, due to begin in just two days.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With such disturbing results from the Chayote fields on our minds we stopped to visit with Andrea Irola, whose family-owned Restaurante El Cas provides our teams with most breakfasts and lunches. We were sad to learn the family patriarch--a masterful groundskeeper and floriculturist--had died a few months earlier but were pleased Andrea and her mother, sisters, and niece were continuing his legacy of tasty indigenous food in an atmosphere of botanical splendor. We were also happy to know Andrea was still maintaining several hummingbird feeders we gave her in 2011 AND that these sugar water sources were attracting a few ruby-throats. This was good news because two males we banded at El Cas returned a year later--the first-ever evidence for Ruby-throated hummingbird site fidelity in this part of Costa Rica.

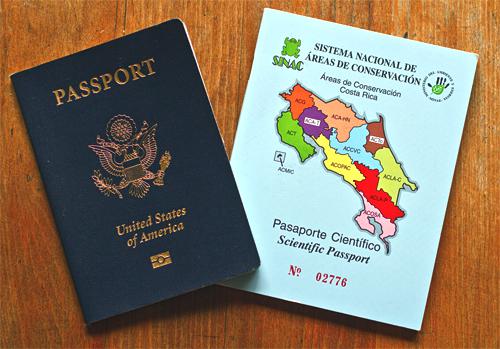

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After confirming Andrea could handle any dietary restrictions for our trip participants we bid farewell to Juan Diego Vargas and set up at the finca for more banana-feeder watching--followed the next morning by the usual snail's-pace drive to and from San Jose to pick up "research passports" (above) from the environmental ministry. We also visited with Paulo Valerio, Holbrook Travel's in-country coordinator, who for ten years has skillfully handled all our lodging, dining, and ground transport--plus all the government red tape involved in approving our research. Without him and Holbrook consultant Debbie Sturdivant Jordan (who first approached us with the idea for a Costa Rica hummingbird expedition 'way back in 2003) our Operation RubyThroat expeditions to Costa Rica would never occur. Profuse thanks to them both! • DAY ONE: The Adventure Begins •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On the morning of Saturday, 8 November a small van picked up the Omega Group at Finca Cristina and whisked us toward the airport, stopping along the way at a hotel to meet up with Alvaro "Chiricuto" Montero (above); this tico bus driver had been so knowledgeable, friendly, and helpful in Ujarrás last year we requested him again for 2014. Also on hand were our first two participants, Bob Ozipko (Irvine CA) and Pat Fitzgerald (Queensbury NY), who had flown in a day or two ahead of the rest of the group.

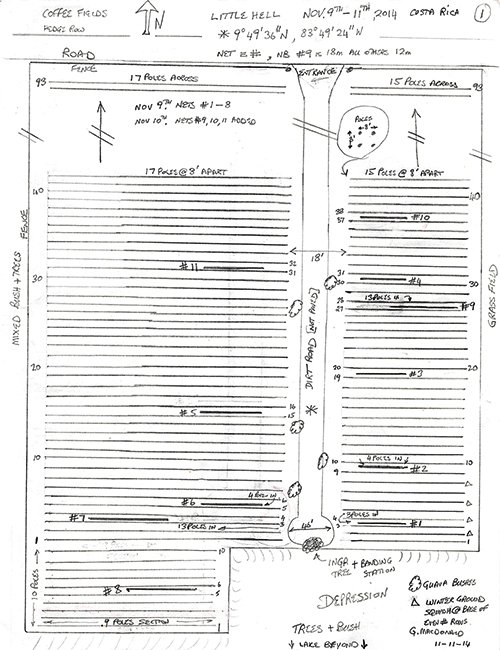

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center From the hotel it was off to the airport to greet the remaining nine participants, including Lesa Hipes (above left, Hinsdale IL); Lisa Spellman Rest (above right, Berwyn IL, and an alumna from Belize back in March 2014); Rita Calandresa (New Rochelle NY); Kathy Mills (Holden MA); Lorraine & Bob Stauber (Westampton NJ); Mary Alice Swope (Gainesville GA); and last--but certainly not least--Mary Kimberly & Gavin MacDonald (Decatur GA), long-time friends and the most stalwart of our Neotropical alumni with an incredible FIVE previous Operation RubyThroat expeditions already under their belts (Costa Rica-West 2009, Belize 2010, Guatemala 2011, Costa Rica-East 2012, AND Nicaragua 2013). Our alumni don't usually go twice to the same location, but Mary had recent experience at various bird banding stations and we wanted her to assist expert Ernesto in the sometimes exhausting task of extracting birds from mist nets at far-flung corners of the Chayote fields; thus, we invited her and Gavin to visit Ujarrás once again. (This year, Pat Fitzgerald also helped in this role.) We likewise admired Gavin's yeoman efforts to produce accurate study site maps for the project's permanent records. (As anticipated, we were not disappointed with these invaluable contributions offered in 2014 by both Mary and Gavin.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As their flights arrived and folks cleared customs we treated everyone to a first taste of Costa Rican food at the airport's outdoor restaurant (above), where most opted for traditional black beans and rice and got acquainted over lunch. When everyone had finished we called for Alvaro, boarded the bus and began our two-hour drive east to the Orosi Valley.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Lesa Hipes agreed to be our designated list keeper--the rule was that at least two people have to see and identify a particular bird to count it on the "Official Group List"--and we began ticking off the usual urban species such as House Sparrow, Rock Pigeon, and Black Vulture. As we left the outskirts of San Jose/Alajuela/Cartago these birds were replaced by "more exotic" species: White-tailed Kite (above, looking down at us from an overcast sky), Tropical Kingbird, Great-tailed Grackle, and White-winged Dove--soon to be followed by dozens more Neotropical birds most of the group had never seen except in field guides they had dreamed over prior to arrival.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center By late afternoon the bus passed through Paraíso and started the long downhill into Orosi Valley and our destination: Tapanti Media Lodge (above)--home base for the nine-day expedition. We stayed at this facility on previous trips and found the rooms to be comfortable (i.e., acceptable beds AND hot water showers--both of which are inviolable requirements for Operation RubyThroat). Suppertime fare was always tasty, and the workers--including our new hostess, Zeidy (Sadie) Portuguez--were very helpful and friendly. After the first evening meal the group gathered in a genuinely plush meeting room for a presentation about our previous Costa Rica hummingbird work and a description of the next day's expectations. We also challenged the group to come up with a memorable nickname to set them apart from the previous 23 expeditions we'd taken to the Neotropics. (Until an acceptable nomination they'd be known only as "The Unnamed." Eventually they, too, would have a distinguished moniker like the pioneering Ujarrás "Chayoteers" from 2011, the 2012 "Chayodoce" team, or last year's well-named "Ujarráscals.") Then it was off to bed early for our travel-weary group.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center • DAY TWO: The Adventure Continues • Early on the morning of 9 November Ernesto made the rounds at Tapanti Media Lodge, knocking woodpecker-like on the door of each participant. It was important to at least start moving before dawn, for we had to board Alvaro's sleek-and-shiny bus (above), travel for 25 minutes to our study site within the Chayote, and take time for a hot, tasty breakfast at Restaurant El Cas--all of which preceded commencement of actual field work. (If the Omega Team were really hard-core we would get folks up a couple of hours earlier and be in the field at the crack of dawn, but we'd rather not run our trips as if participants had been sentenced to hard labor for unknown crimes!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center En route to El Cas we mentioned several Operation RubyThroat traditions--after ten years we have several--one being the awarding of a "magic coin" to the first person who conclusively and confidently identified a Ruby-throated Hummingbird in the field. It didn't take long for Mary Alice Swope--appropriately adorned in a bright red shirt (above right)--to lay claim to the coin (supplied in 2014 by last year's recipient, Leslie Bergum). We hadn't even left the restaurant and the group already knew there was at least one ruby-throat in the neighborhood.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For the sake of continuity and comparison, we had hoped to start field work this year in one of the fields where we'd run mist nets on previous expeditions, but it was Sunday morning and the gates to access roads were locked. The only accessible Chayote plot was at Little Hell where we'd finished up in 2013, so we took a short five-minute drive to that locale. There, the Omega Team (above) demonstrated how to take mist nets from plastic grocery bags and attach them to 10-foot lengths of steel electrical conduit, after which nets were deployed beneath the Chayote arbors.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On paper all this sounds pretty simple but less experienced team members were "all thumbs" at first with various aspects of net building and erection. Nonetheless, everyone caught on pretty quickly and by week's end they were old pros at net deployment.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mist nets we used were the standard four shelves high (above), but because space was limited beneath Chayote arbors we could open only the top three. Net tenders also were careful to avoid tiny tendrils from the Chayote vines, lest they spend more time cleaning nets than catching birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Erecting mist nets to catch birds is sort of like going fishing, except you don't use any bait and simply put the nets where you think you might catch some birds. There's also a lot of sitting and waiting, and you never know from year to year or day to day whether you're going to catch anything at all. In 2013, for example, we caught only 15 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds during six days in the field, so we were eager this year to see what might transpire. We didn't have long to wait. Within ten minutes after putting up our first mist net--and while we were demonstrating a second net preparation for the group--someone called out "Bird!" and we knew we had our first target-bird capture of 2014: A hatch-year male ruby-throat (above) with partial red gorget.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We secured this initial hummer in a white lingerie bag--our preferred method of holding and transporting birds. These bags are of soft material that allows birds to breathe and move without injury, and we can see the bag contents through the mesh. Birds are hung from a line in the shade (above) and processed in the order we capture them. This is a very safe way to hold birds as we work through the measurement and banding process. At day's end each participant takes a couple of bags back to the lodge and hand washes them so we start with a clean set next morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With that first male ruby-throat safely secured in a lingerie bag at 7:30 a.m., it was just 20 minutes until we captured a second RTHU (above)--this time a bird with faint tan streaking typical of females. With two hummers in-hand (actually, "in-bag") we called in the team to demonstrate how we band and collect data from each RTHU.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As a journeyman educator-naturalist, trip leader Hilton particularly enjoys "show-and-tell," when everyone comes in from tending nets for an up-close view of the latest bird-in-the-hand. (This could be Ernesto's LEAST favorite part, since he's charged with running from net to net covering for the team while they're at the banding table. Fortunately, the nets are not too far apart.) Banders never tell the group what a bird might be, preferring to help them work their way to the field guide to make identifications on their own. We find that folks remember their birds much better--and learn a lot more in the process.

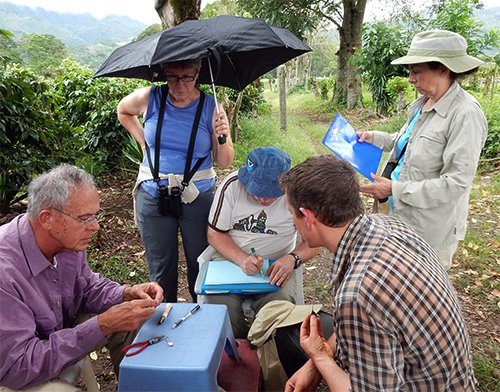

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sometimes Ernesto (above)--a bander-in-training--gets to sit in the bander's seat, assisted by a scribe (to his left) who records data, makes sure all measurements are taken, and verifies a band was applied before the scribe releases the bird. A scribe-in-waiting (alias "scribesmaid") to the bander's right brings each bird to the banding table, reads a paper tag that includes a net location number and time of capture for the bird, and offers the next band to the bander. Participants rotate through these two important roles during the week, giving each person intimate exposure to the whole procedure before returning to tend nets in the field.

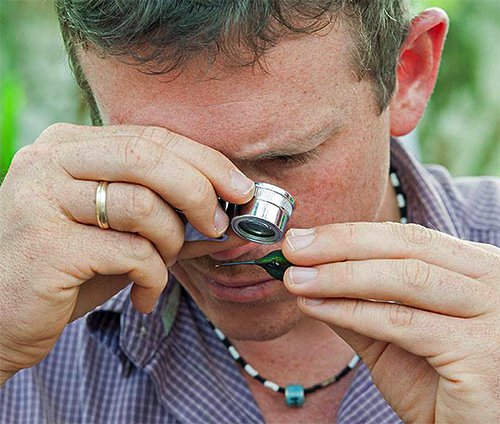

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In addition to time of capture and specific net at which the capture was made, in Ujarrás in November we recorded very detailed data on each Ruby-throated Hummingbird: Apparent age (hatch year or after hatch year); sex; weight (mass); length of wing chord, tail, and bill; throat plumage (amount of streaking and/or number of red gorget feathers); and amount of fat in the furcular depression (just above the breast keel). With a hand lens (above) we also examine the upper mandible for nearly microscopic "corrugations"--tiny etchings that occur all along the upper mandible in young birds and that nearly disappear in older ones.

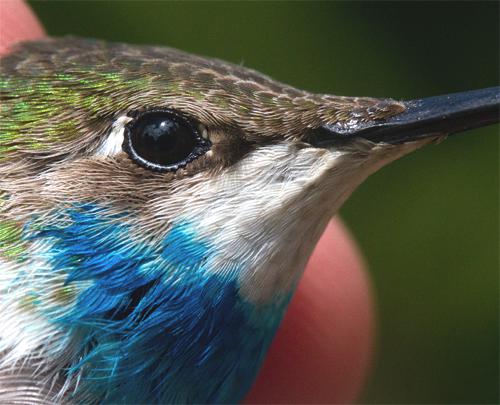

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One especially detailed observation we make concerns the molt condition for each bird's wing and tail feathers. Sometime in late summer but before southbound migration, most Ruby-throated Hummingbirds begin to bring in a few new body feathers, but wing and tail molt occurs only on their wintering grounds. (This makes sense, since a North American RTHU with incompletely molted flight feathers wouldn't fare well during the long southbound migratory flight.) Our earlier expeditions show wing and tail molt well underway by late January in western Costa Rica and essentially complete by mid-March in Belize. Thus, we weren't surprised in mid-November at Ujarrás that very few ruby-throats had even begun flight feather molt; less than 10% of our captures were as far along as the female in the photo above, for whom--counting from inside out--primary feathers #1-3 are new, #4 is partway in, #5 is missing, and #6-10 are old, faded, and somewhat worn.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After all data were recorded and a band was placed on each ruby-throat's leg, we color-marked the hummer's throat or upper breastwith temporary blue dye (above) that facilitated post-banding observations. Our departing gesture for every hummer was to offer a taste of 1:4 sugar water from a feeder hanging near the banding table. Banded birds drank about 80% of the time--some with instant enthusiasm that suggested they were familiar with feeders back north on the breeding grounds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center To say our 2014 group did surprisingly well on that first day in the Little Hell Chayote plot would be an understatement. By quitting time at noon we had mist netted, banded, and released ten hatch-year male Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and two females of indeterminate age--plus the red-gorgetted adult male in the photo above. Day One in the field produced 12 RTHU--just three less than last year's total for the entire expedition!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Mist nets are non-selective, of course, so we often catch species other than our sought-after Ruby-throated Hummingbirds. Our master permit from the Bird Banding lab allows us to apply U.S. bands not just to ruby-throats but to any Neotropical migrants that might show up again in North America. To this end, on Day One we also banded four Tennessee Warblers, an immature male Yellow Warbler, an Ovenbird (above), and a female Summer Tanager.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The most rewarding aspect of banding non-hummers on our Central American sites is that we have encountered a significant number of them in later years--typically very close to where they were originally banded. Such site fidelity was true again in 2014; on Day One the group brought in TWO returns banded as adults in Little Hell by last year's Ujarráscals: A Yellow Warbler (above) banded on 12 November (scribed and released last year by Jim Shuman), and a Tennessee Warbler caught a day later (scribed and released last year by Pat Thompson). Both were males, and both were now categorized as after-second-year birds. Demonstrating such site fidelity is significant because it lends real support to the contention that habitat must be protected within the Central American winter range just as it requires protection on breeding grounds in North America.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center And as we capture--and recapture--North American migrants in our mist nets across Central America, so do we catch tropical birds that are local residents ineligible to receive our U.S. bands. One of the first we netted in 2014 was a Buff-throated Saltator (above), that big-billed species we photographed at the banana feeder at Finca Cristina a few days prior. This bird's diet includes nectar, fruit, buds, and the occasional large insect or caterpillar. Adults are sexually monomorphic (males resemble females).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Costa Rica is home to at lest 51 hummingbird species, more than half of which we have documented in the Chayote fields at Ujarrás. As expected, some of these--16 species to be exact--have also been snared in our mist nets since our first expedition there in 2011. Last year we caught two new species--and they happened to be among the first non-ruby-throats we captured in 2014. The first was a brilliantly colored male Green Thorntail (above), whose iridescent green head changed to azure blue in his lower gorget.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The thorntail's body is actually a bit smaller than that of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird, but its rectrices are amazingly long (above)--more than twice the male's body length. The female has much shorter rectrices and sports a conspicuous white mustache.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In closer view we find the Green Thorntail male sports ten rectrices that are quite different in morphology. The outer two pairs are long and pointed (i.e., thorn-like), but the outermost two are especially long and cross each other in graceful curves. We were particularly pleased to catch this bird in 2014 because last year the only one we captured we accidentally released before good photos could be made.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The second uncommon hummer we caught that first day in 2014 was a male Black-crested Coquette (above), certainly one of the more ornately plumaged trochilids in Costa Rica. Adult males have long black crest feathers, a pointed tan and black necklace, and big bronzy-green spots on the chest. To anyone's eye this bird is quite striking and gives broader meaning to the concept of sexual selection.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It's interesting the thorntail and coquette--both males--were among the final birds captured in Little Hell last year AND two of the first netted there in 2014. This led Ernesto to speculate these may be the very same individuals we caught in 2014--speculation borne out by the behavior of the coquette. Last year after we finished showing-and-telling that bird, he perched calmly on Ernesto's finger (above), allowing numerous photos until we had to shoo him off. This year, our newly caught coquette did exactly the same thing. Too bad we couldn't band him to test 'Nesto's hypothesis!

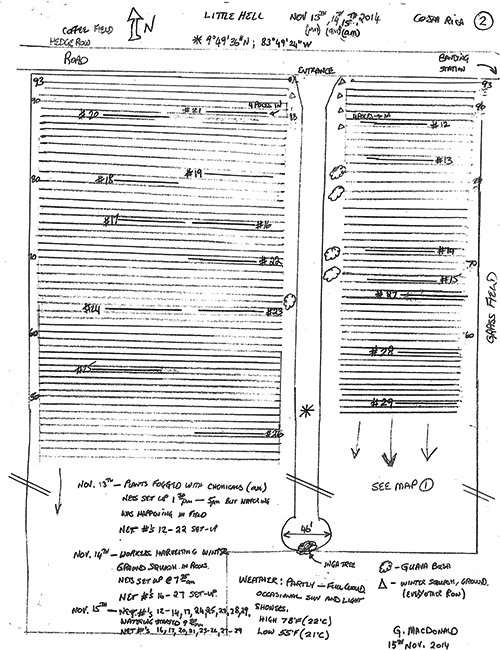

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For the record, we actually netted an amazing NINE different hummingbird species during our first day in the field in 2014. In addition to Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Green Thorntail, and Black-crested Coquette already mentioned, there were Blue-throated Goldentail (above), Violet Sabrewing, Green-breasted Mango, Rufous-tailed Hummingbird, Steely-vented Hummingbird, and Stripe-throated Hermit. We never cease to be impressed at hummer diversity within the nectar-laden Chayote.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Whew! So that was day one in the Chayote fields at Little Hell in Ujarrás: 12 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and seven other Neotropical migrants banded, two recaptures of site-faithful North American songbirds, nettings of several resident non-migrants (most of which we didn't even mention above)--plus two Costa Rican hummers that may have been old friends from last year. After closing nets and loading all our gear back on the bus, we took a short ride back to El Cas for lunch (above).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center All our meals at El Cas were delicious, healthy, ethnic dishes--including special plates (above) prepared for vegetarians and participants with food allergies. It's hard to beat field-ripened produce grown by local farmers and picked that very day, especially when complemented by fresh cheeses and tasty beverages like one made from the fruit of the Cas tree--known in English as "sour guava." (We promise you this: Members of our Operation RubyThroat expeditions will never have cause to complain about the food!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As mentioned earlier, Andrea and the folks at El Cas maintain sugar water feeders for us at least during the months Ruby-throated Hummingbirds are expected in Costa Rica. They never get big numbers of this species--after all, hundreds of acres of nectar-rich Chayote blossoms surround the restaurant--but enough visit for us to operate Dawkins traps (above) during mealtimes. These are passive cylindrical devices made of plastic mesh. There's an open door that allows hummingbirds to enter to feed, but often a hummer forgets how to exit and flies to the top of the cylinder. It's a simple matter for the bander to reach into through the door and gently grasp the bird for banding. Each year we manage to snare a few ruby-throats in the traps at El Cas; in fact, we captured one more immature male on this first day to bring the 2014 total to 13. (NOTE: We've never trapped a female RTHU at El Cas, but one male caught there in 2011 was re-trapped in 2012--the first evidence for ruby-throat side fidelity on the Caribbean slope of Costa Rica!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After lunch the master bander stayed behind to monitor the traps at El Cas while Ernesto led the team on a leisurely walking tour of the ruins (above) of Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Concepción, one of Costa Rica's oldest churches. The structure, now a national monument, was built in the 1580's during the earliest days of colonization by Spain.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A heavily treed park surrounding the ruins connects with the river and is a popular weekend destination for locals and tourists alike. It's also a good place to watch birds and to get views of such tropical epiphytes as the Bucket Orchid, Coryanthes sp. (above). This genus has complex blossoms that temporarily trap a bee before gluing to it a packet of pollen the insect then takes to another flower. Orchids are known for such co-evolved plant-pollinator relationships--one reason they are so difficult to propagate under artificial conditions. By mid-afternoon the group walked back to El Cas, closed down the traps, and boarded the bus for a return to Tapanti Lodge for supper and an evening meeting where all the buzz was about the day's significant success. Then it was off to bed early in anticipation of the next day in the field. • DAY THREE: The Adventure Continues •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Dawn broke on 10 November with a spectacular view of Turrialba Volcano (above). By now the dark ash clouds had been replaced by huge plumes of steam that rose above the peak unbuffeted by wind. After admiring the view, the team quickly boarded the bus at the lodge and headed down toward Ujarrás.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After breakfast and upon arrival at Little Hell, our now-experienced participants grabbed nets (above) and deployed them throughout the Chayote arbors at a faster pace than the day before. Even so, we were already catching birds before all the nets were up: A Tennessee Warbler at 7:15 a.m.,a Mourning Warbler at 7:20 a.m., and our first hatch-year male Ruby-throated Hummingbird of the day at 7:30 a.m. Things clicked along very, very well after those initial captures and we ended the morning with an amazing 26 ruby-throats--20 young males, three red-throated adult males, and three females. Added to the 13 RTHU banded the day before, that gave the 2014 group 39 hummers after just two days in the field--without question an incredible start. To top it off, we also banded 21 Tennessee Warblers, two female Yellow Warblers, and an immature male Mourning Warbler--quite a haul for one morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along with all those banded birds we caught the usual smattering of resident species we photographed and released without banding. Among them were a couple of Blue-gray Tanagers (above), probably the most common thraupids seen throughout most of Costa Rica. These birds are sexually monomorphic but appear to maintain long-term, year-round pair bonds; we almost never saw a solitary individual. All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Folks frequently ask how we're able to get such clear photos of birds. Having them in-the-hand helps, of course, but even for non-banders we advise the following: A good camera (we currently use a Canon 70D); a sharp lens (our is a Canon 60mm macro for most hand-held close-ups, with the 40mm lens for bigger birds); and perhaps the most overlooked or underused secret to good photography--a lightweight but sturdy carbon-fiber tripod (Gitzo brand, in our case, as demonstrated above by the Omega Team). Our traveling camera bag also contains a Canon 300mm telephoto lens with 1.4x telextender for nature action shots, a Canon 28-135 zoom for people pictures and landscapes, and a Canon 100mm macro for miscellaneous close-ups. For good measure both Carman and Hilton tote the compact Canon SX50 . . . but sometimes we just use the high-def camera built into our iPhone 6!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center At morning's end the team packed away nets and field equipment and boarded the bus for a half-hour ride up to Paraíso, home to Finca Cristina--the Carman family's organic shade-grown coffee farm where Ernesto lives when he's not leading tours or doing fieldwork. Greeted by old friends Ernie and Linda, the team had a big lunch--followed, of course, by a freshly roasted and brewed cup or two of that incomparable Cafe Cristina coffee. Afterwards, Linda led the group on a walking tour of the farm, instructing on how to turn an over-worked traditional sun-drenched coffee farm into one that uses shade trees and disdains artificial fertilizers, pesticides, fungicides, herbicides, or other man-made compounds. It's a fascinating story too long to tell here, but we can be grateful there are more and more small farms like this one that eschew toxic chemicals to the benefit of birds and other wildlife. It's not coincidental this little 28-acre tract of land can boast of a phenomenal 315 bird species--including many Neotropicals that migrate through or spend the whole winter.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With her introduction on growing and harvesting coffee complete, Linda moved on to a large concrete pad roofed in translucent polyethylene sheets--the drying area (above). Rather than drying the coffee in big chambers heated by fossil fuels, the Carmans use free non-polluting energy from the sun to dry their coffee beans slowly.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Prior to drying the beans are cleaned and washed in several energy- and water-saving contraptions (above), designed, fabricated, and maintained by Ernie Carman. After drying, similar ingenious homemade devices sort the beans by size and quality; then the product is placed in big sacks for export or goes to the on-site roaster and eventual bagging for sale.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Finca Cristina is a marvelous place that shows what can happen if coffee farmers choose to enhance their land rather than degrade and pollute. Although we always enjoy hearing Linda's inspirational tales, we also just like to wander around taking photos of flora that spring up in the absence of herbicides. Among those plants are nice stands of Lantana, a native species that attracts substantial numbers of hummingbirds, butterflies, and other nectar-loving fauna.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along with flowering species at the finca grow numerous varieties of ferns. These relatively primitive plants reproduce not by seed but by spores borne on the undersides of leafy fronds (see photo above). Each bump represents a cluster of dozens of spores that will be released when mature.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Various plants on the Carman's organic coffee farm might be considered "weeds" by some observers, including an unidentified member of the Nightshade Family, Solanaceae (above). If this flower looks like something growing in your garden, it's because tomatoes are in this family. The presence of a tiny invertebrate (also unidentified) on the uppermost half-inch-wide blossom is evidence insecticides are NOT in use at Finca Cristina. (NOTE: For any unidentified flora or fauna on this page, if you know a common or scientific name please e-mail it to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Since Finca Cristina uses no fungicides, the Carmans are faced with a constant onslaught of leaf fungi that can substantially reduce productivity by their coffee trees. To thwart the threat, Ernie sprays his trees with spores from a beneficial fungus he cultivates in his lab. Both fungi are present on the leaf above, the goal being for the beneficial fungus to out-compete the detrimental one. After 30 years Ernie and Linda have found the relationship between insects, fungi, bacteria, coffee plants to be exceedingly complex, but their on-going studies have led to several biological controls such as this one. After an educational and pleasant afternoon at Finca Cristina, the team returned to Tapanti Lodge for supper. At the evening meeting a panel of anonymous judges took into account all nominations made for a nickname for the 2014 Ujarrás group and unanimously concluded they would be known now and forevermore as the "HellBanders." To the esteemed judges this seemed like a perfectly appropriate name--a take-off on the "Hellbender" salamander of North America--and indicative the group was apparently going to spend all its field days running mist nets in "Little Hell." • DAY FOUR: The Adventure Continues •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Sunrise on 11 November was our most colorful of the nine-day period in Costa Rica, with pink and purple light bathing the steam cloud above Turrialba (above). The HellBanders were pleased at the sight but were eager to board the bus, which they did on-time and in their usual good spirits.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Enthused by the previous day's abundance of banded Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, the HellBanders quickly got down to business after breakfast at El Cas and unfurled more than a dozen nets throughout the Chayote plot at Little Hell. This enthusiasm paid off quickly, with female ruby-throats captured at 7:10 a.m., 7:15 a.m.,and 7:20 a.m.--followed by immature males at 7:35 a.m., 7:45 a.m., and 8 a.m. Things gradually slowed as the morning went on, but the team still ended up with 13 RTHU (nine hatch-year males, one adult male, and five females), bringing the three-day total to 54--more than we had caught in all of 2011 (43 RTHU) or 2012 (50 RTHU), and three times the 15 banded the previous year by the Ujarráscals. Bonus birds this day included 25 Tennessee Warblers, but the real Neotropical treat came when the HellBanders netted TWO TEWA banded on 12 November 2013 (both scribed and released last year by Jim Shuman) AND a second-year male Yellow Warbler banded a day later (scribed and released last year by Judy Schwarzmeier); all three birds were from Little Hell. Once again, these birds must have departed sometime during the spring of 2013, flew north, and returned to Costa Rica during autumn migration; banding and recapturing these non-hummingbirds again revealed something very significant about avian site fidelity within the Chayote fields.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On 11 November we added two new species to our list of hummingbirds netted in the Chayote. The first was a male Crowned Woodnymph (above). Formerly called Violet-crowned Woodnymph, this colorful and common species causes disagreement among taxonomists who are trying to sort out its actual distribution and classification.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The other new hummer we netted was less controversial and very different in appearance from the other ten captured thus far. It was a Brown Violet-ear (above). If most hummingbirds are reminiscent of aerobatic jet fighters, this one is more of a cargo plane with short bill, stout body, and camouflaged plumage.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite is lumbering appearance this hummer still has its share of color, with a rusty rump and iridescence on its gorget and face. Based on the yellow gape--the area at the base of the mandibles--we judged this individual to be an apparent juvenile; a gape typically darkens as the bird ages.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center In the U.S., backyard birdwatchers who scatter cracked corn and white millet often attract White-throated Sparrows to wintertime feeders. Some of those same folks take WTSP for granted, but we see them as among the most elegant birds in North America. Then we come to Costa Rica, where we encounter a relative of the white-throated that nearly knocks our socks off--none other than the Rufous-collared Sparrow (above). This bird shares a white throat and prominent head-striping with its more northerly cousin, but add to that dashes of rust and slate gray and the rufous-collared is all decked out in formal attire. (Sparrows are SO under-appreciated we just wanted to give this bird its due.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center For lunch the team returned to El Cas, where the hanging banana cluster continued to attract all sorts of birds. The HellBanders were delighted to watch and photograph an adult male Baltimore Oriole (above) with brilliant plumage as he dominated the yellow fruit and ate his fill. Beginning birders are understandably surprised to learn this predominantly orange creature is actually a member of the Blackbird Family (Icteridae).

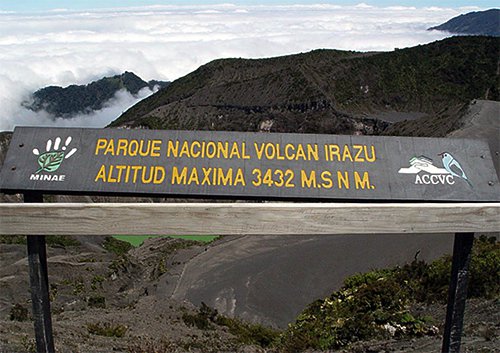

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After lunch we boarded Alvaro's bus for the long climb out of the Orosi Valley and up the slopes of Irazú--the huge shield volcano that looms over Cartago and Paraíso. At its highest point Irazú reaches 11,260'--enough altitude to cause some tourists a little discomfort. The HellBanders did fine, however, and after passing through several cloud layers along the way bounced out of the bus to begin to exploring the mountain. We felt fortunate to be able to take this field trip, knowing just a week or so ago Irazú had been closed because of the danger posed by windblown ash from neighboring Turrialba Volcano.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Irazú is indeed enormous, covering nearly 200 square miles. It's also the tallest active volcano in Costa Rica and has several craters and calderas, some of which spew clouds of sulfurous gas and others of which contain lakes or ash deposits. Pictured above is the green water of Diego de la Haya, the near rim of which is hidden by giant six-foot-diameter leaves of Poor Man's Umbrella, Gunnera insignis.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Much of the landscape atop Irazú looked more lunar than earthly, so when the group came to a patch of Indian Paintbrush (above), the contrast against grays and blacks was especially striking. Although various species of its genus (Castilleja) are found from the Andes north to Alaska and even in Asia, this particular plant was C. irazuensis--an endemic named for the very volcano on which we found it growing.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Despite the apparent desolation of the mountaintop, the HellBanders (above) found plenty to look at, including such high-altitude birds as Slaty Flowerpiercers, Slaty-backed Nightingale-Thrushes, and Volcano Juncos.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of our "target birds," however, was Volcano Hummingbird--an endemic species not usually seen except on the highest peaks in southern Costa Rica and Panama. (Oddly enough, this is one of the 27 hummer species we have observed in lower-altitude Chayote fields at Ujarrás.) As we approached the big ash flat near the top of the mountain the team was pleased to spot a male hummer perched on a tall shrub (above). The light wasn't great, but we could still see throat feathers that were the pinkish-purple typical of individuals on Irazú and Turrialba. Volcano Hummingbirds on other peaks have gorgets of different hues--purplish-gray in the Talamancas and red on Poas and Barva.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Irazú's ash flat is indeed desolate (above), with only a few plants able to grow toward its center where more moisture is available. It's remarkable this harsh habitat supports so many species of birds and other wildlife--including Coyotes we have seen on previous trips. Coyotes prey upon small mammals, which suggests there are lots of seeds available for mice and rats--all of which indicates a well-developed co-evolved ecosystem up there in the clouds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the showier plants in full bloom in mid-November was a three-foot-tall composite with multiple yellow flowers and grayish stems. This was Senecio oerstedianus, one of the sunflowers (Asteraceae) known as "groundsels." Its flowers are pollinated primarily by a native bumblebee--further indication of the complexity of life at this high altitude.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because the ash flat on Irazú was safely navigable on foot, we decided to see if we could circle around for a better photo of that male Volcano Hummingbird we had seen on the way in. Sure enough, he stayed tight on his territory as we approached, so we fired off a few shots. The light still wasn't very good and he was back-lit (above), but our closer view clearly showed how his gorget included elongated feathers at the edges. Volcano Hummingbirds are among the smaller trochilid species, perhaps two-thirds the size of an average ruby-throat. Incidentally, the Volcano Hummingbird's scientific name is Selasphorus flammula, putting it in the same genus as Rufous Hummingbirds, S. rufus, that breed in northwestern North America and regularly show up in winter across the eastern U.S.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As our tip to Irazú neared its close, Ernesto told us he had an one more show-and-tell and pulled out a 20 million colones note issued by the Costa Rican government. On it were etchings of two organisms, the Volcano Hummingbird and the Senecio sunflower--evidence that ticos were aware and proud of Irazú Volcano and its unique assemblage of animals and plants. • DAY FIVE: The Adventure Continues •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After three early morning field days catching hummingbirds in the Chayote, we let the team sleep in a little on 12 November for our traditional "Hump Day." Although most afternoons are devoted to short field trips, some very interesting sites are further away, so when possible we like to set aside a whole day for travel and exploration. This year, as usual, we wanted to take the team to Rancho Naturalista, an internationally acclaimed bird lodge two hours away toward the Caribbean Coast. There are several ways to get to Rancho, but this time Ernesto suggested Alvaro drive over a new route that took us past Rio Pejibaye (above), a fast-flowing mountain stream shaded by overhanging vegetation. This habitat was bound to host bird species we might not see elsewhere, so at this first stop the HellBanders excitedly exited the bus with binoculars, cameras, and spotting scopes.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center It wasn't long after we started scanning the rock-lined stream that someone called out "wader!" and directed everyone's attention toward a long-legged, straight-billed, brown-and-white bird on the far bank (above). There was no doubt this was one of the ardeids (AKA herons and egrets), but it was a species new to most members of the group. After consulting Costa Rican field guides, the HellBanders came up with a definitive identification: Immature Fasciated Tiger Heron. (We originally thought this to be a Bare-throated Tiger Heron, but in that species feathers showing at the base of the lower bill would be yellowish rather than white.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A few minutes later another rock-hopping bird showed up, but despite its general appearance this was no egret or heron. Instead, this was a Sunbittern, an unusual species that is the only member of its family (Eurypygidae). Sunbitterns have an ancient lineage that may go back to Gondwanaland days when all the continents were still joined. When courting or alarmed the Sunbittern extends one or both wings, revealing a giant eye spot that undoubtedly attracts a mate and/or startles potential enemies.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The canyon walls along Rio Pejibaye were almost vertical and in some spots water oozed from a bare rock face. These seeps attracted numerous butterflies we could not identify, including the orange-winged species above. The butterflies got water from the seeps, but it's likely they were more intent on lapping up dissolved minerals needed for successful reproduction. (NOTE: For any unidentified flora or fauna on this page, if you know a common or scientific name please e-mail it to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One unidentified butterfly near the seep elicited a great deal of admiration from the group. As one HellBander described it, the insect's wings (above) looked like they were made of crushed black velvet.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The most colorful lepidopteran we saw along the river wasn't even a butterfly, but a rainbow-hued Tiger Moth, Cyanopepla submacula (above), with feathery antennae. This unidentified creature's psychedelic colors literally glowed in the sunlight. Their function, we would guess, is aposematic; i.e., the colors serve as warning to potential predators that this diurnal moth isn't very tasty.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Large insects seemed to abound along the river, including an inch-long black beetle (above) scurrying along a sandy area. This almost certainly was a Scarab (Dung) Beetle, possibly one of the Rhinoceros Beetles (Dynastinae, in the Phileurini tribe). We were impressed by hundreds of tiny pits on its elytra (hard wing covers) and thorax. We're guessing the brown matter in the pits is at least partly animal droppings.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Not far from the beetle, keen-eyed Ernesto somehow spotted a highly camouflaged eight-inch-long reptile (above) curled around a plant stem and half-hidden beneath a leaf. It was a little Eyelash Viper, Bothriechis schlegelii, whose superciliary scales resemble eyelashes. These little moderately poisonous pit vipers are related to rattlesnakes, copperheads, and cottonmouths but at a maximum length of 32" never reach the sizes of their North American kin. Eyelash Vipers occur from southern Mexico to northern South America; across their range they are highly variable in color and pattern. These snakes are arboreal lurkers that lie in wait for lizards and small birds, sometimes twitching their light-colored tails as bait.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Following an eventful 90 minutes on the banks of the Rio Pejibaye, the group journeyed on toward Rancho Naturalista (above), where Ernesto once worked as a resident guide. After a bathroom break the team went straight for the Rancho's second-floor balcony, festooned with hummingbird feeders and overhanging a garden to which water features and bananas bring other sorts of birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One of the first hummers to appear was the almost omnipresent Rufous-tailed Hummingbird (above), a sexually monomorphic species our team knew well from netting far too many of them back in Little Hell. In our estimation this is one of the half-dozen or so most common of all 340 hummingbird species, with a range from central Mexico to Ecuador and Peru. Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds are also quite aggressive and often drive other trochilid species away from feeders and territories. Extensive red coloring in this bird's mandibles suggested it was older and in prime condition.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another familiar species that showed up to feed on flowers in a hedge of Blue Vervain was an adult Black-crested Coquette, a species we had in-the-hand back on our first day at Little Hell. This hummer feeds more commonly in the canopy or subcanopy but comes to ground level when nectar-rich sources are available.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Numerous hummers were visiting the vervain hedge and Rancho's plentiful feeders, but quite a few were just perching and preening. The female Crowned Woodnymph (above) was particularly camera-friendly and for long periods sat still for close-up photos.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center A couple of male Crowned Woodnymphs (above) also frequented a thorny shrub near the balcony at Rancho. They were a bit more jumpy than the females--it probably comes with high testosterone--but we were able to get some shots of their iridescent plumage. The violet in their crowns and breasts was so intense it almost overloaded the sensors of the camera!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Back at the feeders White-necked Jacobins were zooming in and out at a rapid pace, except for one female (above) that paused to feed for a few extra seconds. The male in this species dresses in more "formal" dark blue attire, while the female has a spotted belly and throat.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As mentioned, water and banana feeders at Rancho attract birds other than hummers, as shown by a female Summer Tanager (above) that came in to drink, bathe, and scratch through the earth for seeds and insects. The bill in this Neotropical migrant species is noticeably larger than that in the closely related Scarlet Tanager. After a terrific morning of birding from the balcony at Rancho Naturalista we retired to the downstairs veranda for a delicious lunch. Prior to departing the group made one last effort to find the lodge's signature hummer--the Snowcap. We were stunned when right in front of us one was pinned to the ground by an aggressive Rufous-tailed Hummingbird. The larger bird actually grasped the Snowcap in its talons and lifted it into the air a few inches before letting go.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With that Snowcap vs. Rufous-tailed scenario in our minds we boarded the bus and headed back west for a planned stop at CATIE, the Tropical Agricultural Research & Higher Education Center at Turrialba. Rancho Naturalista had one more delight for us, however, when an adult Roadside Hawk (above) perched in a tree on our way down the mountain.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Since 1973, CATIE's mission has been "to contribute to rural poverty reduction by promoting competitive and sustainable agriculture and natural resource management, through higher education, research, and technical cooperation." To paraphrase the organization's Web site, as it fulfills its mission CATIE ultimately benefits: 1) Small and medium-sized low-resource farmers including those in extreme poverty, and those with minimum means to diversify and become competitive; 2) rural communities and local organizations; and, 3) Business-oriented farmers and agroindustrial entrepreneurs generating rural employment.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we waited for our tour guide, Ernesto stepped back into the woods behind the visitor center and did a double-take. In a dark depression among dead palm fronds on the ground in front of him he somehow noticed a tightly coiled serpent, this time a four-foot-long Fer-de-Lance, Bothrops asper (above). During more than two-dozen previous expeditions to Central America we've seen less than a half-dozen snakes, but Hump Day 2014 had already tallied the Eyelash Viper and this much larger, deadlier species. The Fer-de-Lance, also a pit viper, is considered to be the most dangerous snake in Costa Rica, if only because it's found in a wide range of habitats that include agricultural sites and even urban areas. A fully grown adult can reach six feet in length and inject what amounts to an overdose of toxic venom. Hatchlings--poisonous from birth--tend to be arboreal and often hang out in Coffee trees, much to the chagrin of workers picking the beans. Nonetheless, it was exciting to finally observe and photograph this species in the wild, and to notice the HellBanders were intensely interested and not the slightest bit serpentophobic.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our guide (above), an CATIE graduate student we knew from past trips, was very knowledgeable about the facility and the many fruits he displayed on a long table. These included everything from palm nuts to cacao pods--all being grown on small farms somewhere within CATIE's sphere of influence.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We were especially intrigued by a display of the Monkey Pot Tree, Lecythis zabucajo (above). This Amazonian relative of the Brazil Nut produces a pod containing numerous fruits held inside by an lid-like operculum that must be removed. The plant's nickname comes from a traditional tale that to catch a monkey you place something sweet inside the pod; when the monkey reaches in and grabs the treat, the resulting fist keeps the monkey from withdrawing its hand.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Our knowledgeable guide led the HellBanders through the arboretum (above), pointing out economically and environmentally important flora. Early on the tour, however, he directed the group's attention to a small pond along the path.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center There, sunning itself on a tangle of old roots (above) was an Orange-eared Slider, Trachemys scripta venusta, the Costa Rican counterpart to North America's Red-eared Slider, T. s. emolli. These closely related subspecies, known collectively as "pond sliders" for their habit of slipping down pond banks when disturbed, are among those organisms whose taxonomy is in flux; don't be surprised to read some different scientific name for Orange-eared Slider.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center On a fence post beside the turtle pond was a bird with a familiar shape and behavior but unfamiliar plumage. In silhouette it looked just like an Eastern Phoebe we see back home at Hilton Pond Center and, in fact, was its close relative: Black Phoebe. Although this tyrant flycatcher--all dark except for a white belly and crissum--is often associated with Central America, it also breeds from Oregon south through California and Mexico. Like its eastern U.S. counterpart, the Black Phoebe bobs and wags its tail frequently and hawks insects from a favorite perch.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Along the trail our guide pointed out numerous woody plants, one of the most striking being a Cannonball Tree, Couroupita guanensis (above). This South American native is obviously named for numerous spherical fruits produced from flowers on its trunk. Within the woody eight-inch pod are as many as 500 seeds relished by peccaries and smaller mammals. Farmers harvest the odoriferous fruit as food for chickens and pigs.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Everything at CATIE was interesting, but one sighting we especially liked was a cryptically colored moth (above). Although most moths fold wings back along their bodies when at rest, this unidentified individual rolled its white-tipped wings and held them perpendicular, tucked its head under (with antennae barely visible), and raised the posterior tip of its abdomen. We pondered this behavior for a long time and finally concluded the moth's markings and posture made it resemble a scorpion--a poisonous invertebrate birds and other predators might be inclined to avoid, thus sparing the moth. (NOTE: For any unidentified flora or fauna on this page, if you know a common or scientific name please e-mail it to INFO.) • DAY SIX: The Adventure Continues •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Rested and rejuvenated from Hump Day, the HellBanders were ready to go early on the morning of 13 November. We reported as usual for breakfast at El Cas and headed toward our study site for another day of netting and banding. Along the way we had a nice panoramic view (above), looking out over a vast Chayote field toward Turrialba (on the right) and its steam cloud that drifted all the way to Irazú. When we got to Little Hell, however, the plantation owner had a little surprise for us: That particular plot had been scheduled this day for chemical spraying, and we weren't sure whether it was fertilizer, pesticide, herbicide, or what. We weren't about to expose our group to whatever airborne compounds they might be applying, so we made a quick retreat and drove back to scout some of the other Chayote fields we had worked in past years. The HellBanders fanned out with binoculars at the ready, but after 30 minutes of looking for Ruby-throated Hummingbirds we concluded there just weren't any in these mature plots apparently past their nectar-producing prime. Rather than lose a day of field work, we made an impromptu decision to flip the day's schedule by moving our banding time from the morning slot. With that, we re-boarded the bus and drove toward Tapanti National Park--which we had planned to visit that afternoon. One thing we've learned after years of field studies is it pays to be flexible!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Tapanti National Park (see map above)--sometimes referred to as Orosi National Park--is on the south edge of the Talamanca Mountain range. It covers 12,500 acres and includes two main bioregions: Lower montane and pre-montane cloud forest that receive up to an incredible 280" of precipitation annually. (That's more than 13 feet!)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Because Tapanti is indeed a rain forest it's unusual to have a sunny day field trip but that's exactly what happened in 2014--after last year's group got completely soaked. All that moisture makes for plenty of vegetative diversity that, in turn, hosts 45 mammalian species, 28 herptiles, and 400 kinds of resident and migratory birds.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The first mammal we came across was rooting through muddy ground beside the road at the park's visitor center. With its erect round tail and long snout we recognized this as a White-nosed Coatimundi, Nasua narica (above), a member of the Raccoon Family (Procyonidae).

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Unlike Raccoons, coatis are primarily diurnal, spending the day in search of insects, lizards, fruit, roots, and bird and reptile eggs. Coatis are typically gregarious, hanging out in groups of up to two dozen noisy individuals. The one we found at Tapanti was apparently an old male who for some reason was leading a solitary existence.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Prolific flowers make for lots of pollinators, so we weren't surprised at Tapanti National Park to find lots of butterflies. Among our favorites was an unidentified Clearwing (above), so called because their membranous wings lack scales and are nearly transparent.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another pollinator hovering in the tree tops was a hummingbird with a distinctively striped face, decurved bill, and long tail. This was a Long-billed Hermit (above)--formerly known as Long-tailed Hermit--and a species whose actual taxonomy is a topic of frequent discussion among ornithologists because of disjunct and slightly dissimilar populations ranging from Mexico to northern South America. The central tail feathers of this large hummingbird are longer than the rest.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we gazed skyward at hummingbirds and butterflies--and the Moon (above)--we were impressed with the great diversity of epiphytes growing in Tapanti National Park. Lots of moisture--even when it's not raining the humidity is high and foggy conditions may prevail--provide the water these "air plants" need to survive without having roots in the soil.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Virtually every tree branch at Tapanti contains a lush assortment of green plants., from orchids to bromeliads and ferns to mosses. Lichens--with their symbiotic algae and fungi--rounded out the vegetative community, particularly on dryer parts of tree limbs and trunks.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With orchids demanding top dollar from florists back home in the U.S., it's always interesting to see these complex flowers growing wild across the tropics. The unidentified white variety above literally glowed in bright sunlight.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also glowing in the sun's rays were clusters of fuzzy blue berries growing on weedy shrubs along the trail at Tapanti. Again, we could not identify their species but were fascinated by their unusual color. (NOTE: For any unidentified flora or fauna on this page, if you know a common or scientific name please e-mail it to INFO.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center With all that rainfall in Tapanti National Park, one might expect lots of cold-water tributaries. One that arises in this watershed is the Rio Grande de Orosi (above), which flows past our Chayote study site at Little Hell and into Lake Cachi.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Tapanti National Park also boasts of several waterfalls, including Kettle Falls (above). This falls is at least one-hundred feet tall and becomes especially thunderous after heavy rainstorms.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As we departed the boundaries of Tapanti National Park we stopped several times to look at birds and flora. Perched on a bare eucalyptus branch (above) was an adult Broad-winged Hawk so close we could see its red iris--a sign of maturity in some raptors that have yellow irises as youngsters.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Just outside the park was a well-established coffee nursery (above), where tiny seedlings are started in one-gallon plastic bags filled with rich soil.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Depending on time of year, the nursery holds tens of thousands of these bagged seedlings. Once planted the baby coffee trees grow rapidly and begin bearing fruit in about their seventh year. Optimal productivity continues until about year 20, although proper pruning can extend the berry-producing life of a tree. When productivity drops farmers cut down the coffee trees and use their dense wood for everything from cooking rotisserie chicken to primitive carvings. (NOTE: The maximum age of a coffee tree is about 100 years, but such ancient plants seldom produce berries.)

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After the morning field trip we drove back to El Cas for lunch, joined by several Blue-gray Tanagers (above) feasting on that bunch of bananas hanging near the restaurant. When the group's meal was finished we headed back to Little Hell; workers who had been spraying that morning had finished their task and were nowhere to be seen. We weren't sure how afternoon banding would work; our only previous after-lunch attempt came in 2011 when the bander was ill one morning and we flip-flopped the daily schedule. In any case, the HellBanders were willing to give it a try and quickly deployed their nets. By 1:30 pm they caught the first female Ruby-throated Hummingbird, followed by an immature male 15 minutes later. It turns out afternoon banding wasn't so bad after all. The team managed to capture a phenomenal number of ruby-throats: 25 hatch-year males, three adult males, and six females for a total of 34! Looking at our past 24 Operation RubyThroat Neotropical expeditions, this was an all-time record for a half-day of work! It's hard to explain why we were so successful that particular afternoon. Had the workers who were spraying kept the hummers from feeding that morning? Had a big wave of RTHU just arrived from elsewhere? Or, as Ernesto observed, did a near-absence of aggressively territorial Rufous-tailed Hummingbirds during the afternoon give smaller ruby-throats more opportunity to fly about the Chayote and feed? We can't know for sure, of course, but next year we may try an afternoon banding session just for comparison.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Among the fully gorgetted adult male RTHU we captured was one that looked quite different. About half his iridescent throat feathers were noticeably GREEN! Although we've banded more than 7,000 Ruby-throated Hummingbirds in the U.S. and five Central American countries, we had never seen this coloration before. It's not uncommon for ruby-throats to have red feathers that have degraded to a bronzy color, but emerald green was a new aberration.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Hummingbird colors are not caused by pigments in different hues but by structural attributes of the plumage. Different configurations of tiny grooves and air bubbles embedded in the feathers scatter light in different wavelengths such that one feather appears red while another looks green. When we looked at the back of the green-throated ruby-throat we notice those feathers were also abnormal, with several having no iridescence; this made those feathers look black, the result of underlying black melanin pigment showing through. Our guess is that due to some genetic defect this particular hummingbird was growing feathers with abnormally configured grooves and bubbles. Along with this one unusual RTHU and 33 "normal" ones, the HellBanders also netted five Tennessee Warblers and one Yellow Warbler during our afternoon session. This was fewer passerines than during our usual morning time slot, but the hummers more than made up for it. • DAY SEVEN: The Adventure Continues •

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After their wildly successful afternoon of capturing hummingbirds the day before, the HellBanders were eager to see what might transpire on the morning of 14 November and were on the bus ready to go several minutes ahead of time. The day turned out to be overcast and a bit misty--not enough precipitation to force closing the nets but enough to require Mary Kimberly (above) to protect our all-important data sheets with a foldable umbrella while Bob Stauber scribed furiously while both Bill and Ernesto measured and banded hummingbirds. The team didn't reach that record-setting 34 ruby-throats from the previous afternoon, but by morning's end still had a more-than-respectable total of 20 hummers banded, including 12 immature males, three adult males, and five females.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Passerine birds were also plentiful with bandings of 18 Tennessee Warblers and two Yellow Warblers. Two after-second year male Baltimore Orioles in bright plumage (above) were our "eye candy" for the morning.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center The farmers at Ujarrás are quite resourceful, often using their Chayote fields for more than one purpose. Such was the case this year in Little Hell, where workers had planted rows of squash beneath the arbors. The HellBanders were careful not to step on the six-inch squash flowers as they tended their nets. The big yellow-orange blossoms were one more nectar source for potential pollinators such as fruit flies and a Honeybee in the photo above.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Apparently those pollinators were doing a good job, and on a couple of days during the week workers paused from picking Chayote fruit long enough to bring in the squash harvest (above). While much of the Chayote crop from Ujarrás is exported to the U.S., we figured the squash was destined for produce stands in and around Cartago, San Jose, and Paraíso.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Also growing in a hedgerow at the edge of the Chayote was a much smaller two-inch yellow flower (above) that we suspect was some other member of the squash family. We may be completely wrong on this one, however, so be sure to let us know at INFO if you have a definitive identification.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center One other unidentified blossom caught our eye as we explored the hedgerow. This one (above) was purple and about an inch or so across.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After a productive morning in the field, the HellBanders made for lunch at El Cas, where we had a little time to set and run the Dawkin's traps. This turned out to be a good thing because there we were able to capture and band one more male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, this time an adult male with full red gorget--giving us 21 for the day. No one was more delighted than Andrea (above), who faithfully maintains the restaurant feeders for us and was rewarded with an opportunity to release the hummer after banding. We were able to trap only two RTHU at El Cas this year, but one never knows when it might be these very birds that show up back in North America--especially since they're apparently accustomed to visiting sugar water feeders.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center While we watched the Dawkins traps for hummingbirds, our attention once again was diverted to that hanging bunch of bananas. This time the fruit-hungry visitor was a female Passerini's Tanager (above), whose male counterpart is jet back with a bright crimson rump.

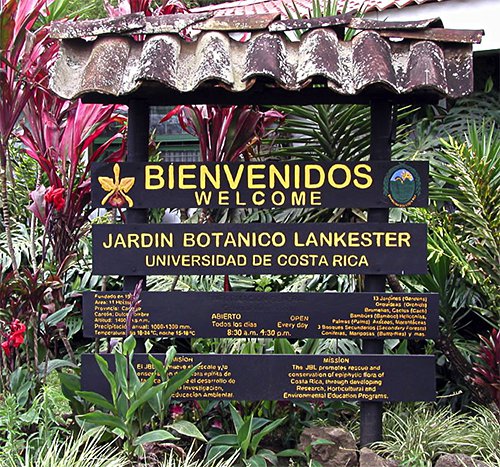

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center After lunch at El Cas it was off to nearby Cartago and an afternoon walking tour of Lankester Botanical Garden. This facility is associated with the University of Costa Rica and is internationally known for ground-breaking work on orchid distribution and taxonomy. It also happens to be where Ernesto Carman first got interested in natural history, initially with orchids--as an 8-year-old--and later with birds. The rest is history!

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Lankester is a bit different from your typical conservatory or botanical garden because it is a working laboratory with an extensive collection of type specimens. Many are not showy orchids, but Lankester still has some of the big blossoms on display. One of these is Ascocenda (above)--abbreviated in the horticultural trade as Ascda--a man-made hybrid genus resulting from a cross between Ascocentrum and Vanda.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center As mentioned previously, some orchids have very complex relationships with their pollinators that may be attracted because of fragrance or the flower's physical resemblance to an insect. The larger unidentified orchid above had a center of rich brown--a color seldom seen on flowers; the shiny color was reminiscent of fresh animal droppings, which may be why a fly was checking out the nectar-bearing structure.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another somewhat smaller (two-inch-wide) but still showy orchid, in this case Dendrobium bifalce (above), also showed hints of brown against yellow-green petals. This species is non-native to Costa Rica, having been imported from New Guinea by orchid fanciers.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Big orchids are eye-pleasing, but at Lankester Garden we are always drawn to the miniature orchids--flowers so small they're likely to be overlooked by many observers. The one above is one of our all-time favorites--a Lepanthes species with translucent orange blossoms only a quarter-inch from top to bottom. In this orchid the flowers are produced alternately and sequentially along a stem that lies flat against a grayish leaf.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center Another quarter-inch mini-flower was borne on this Diodonopsis sp. (above). Again translucent, this native Costa Rican orchid yields solitary blossoms with white hair-like structures surrounding the base.

All text, maps, charts & photos © Hilton Pond Center We enjoy all the miniature orchids in Lankester Botanical Garden's research collection but especially like Dresslerella pilosissima (above), named for Dr. Robert L. Dressler. This esteemed and elegant gentleman--a world expert and published author on orchid taxonomy--has served many years as director of the facility. • DAY EIGHT: The Adventure Continues •